In 2021, the head of the Tajik Drug Control Agency was cited by

TASS News as having said that the volume of intercepted heroin and hashish had doubled over the last year, from

2.3 tonnes in 2020 to 4 tonnes in 2021. These narcotics are cultivated, produced, and trafficked primarily from Afghanistan. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC)estimates that

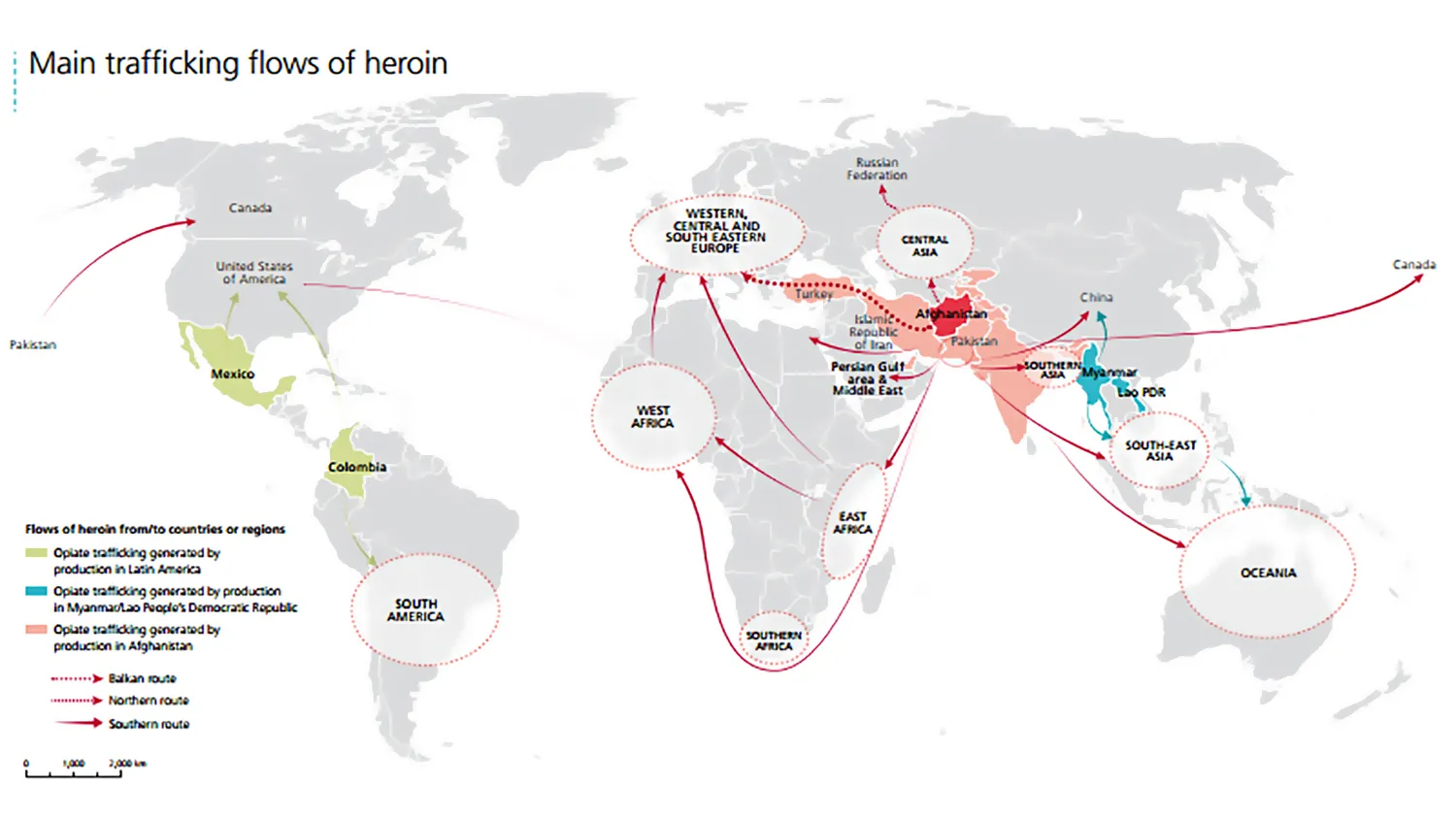

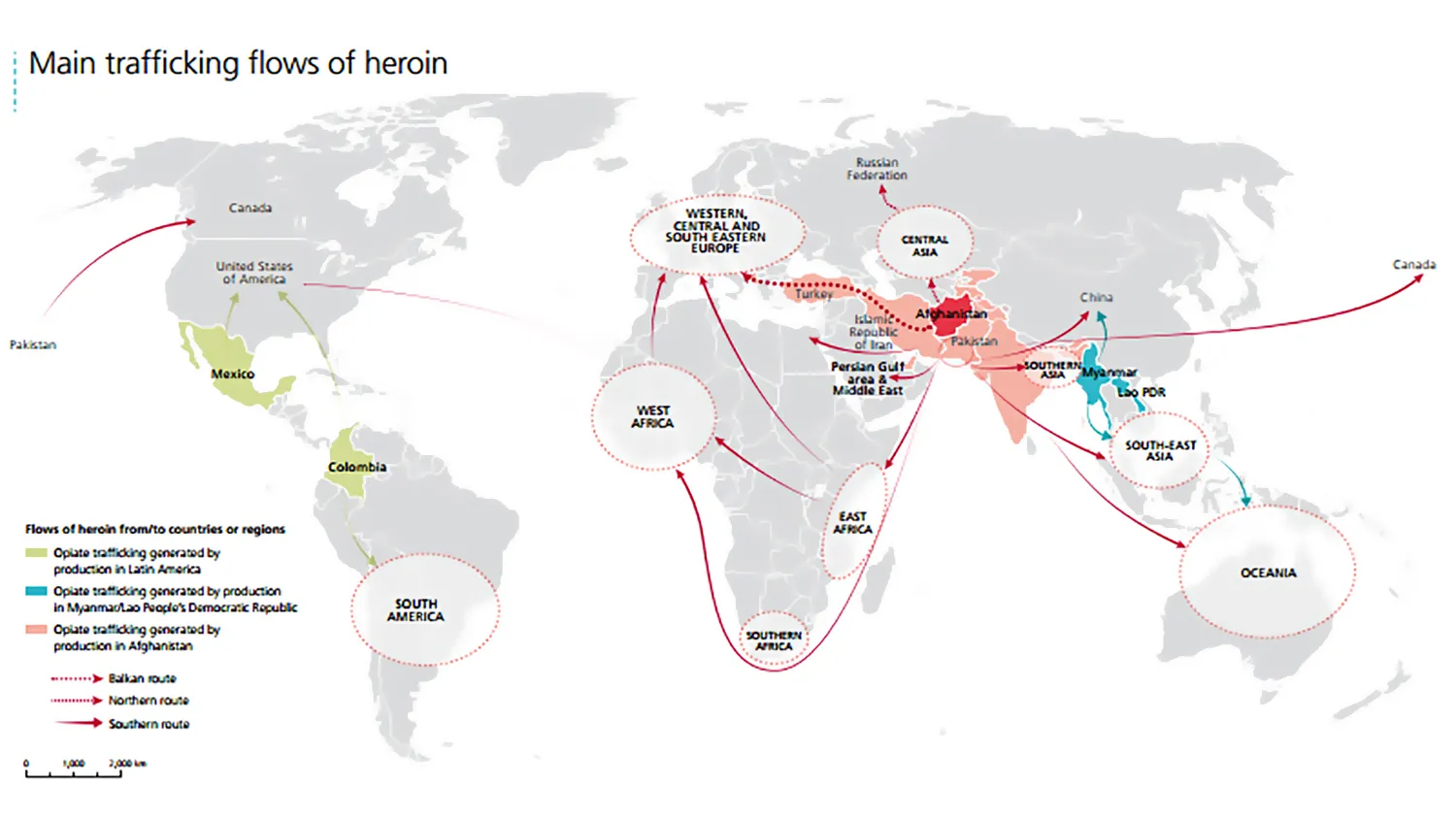

80 percent of the world’s opium and heroin supplies are trafficked from Afghanistan along three primary routes into greater Asia and Europe, and pose a serious threat to the health and safety of citizens in these regions. The recent events in Afghanistan and Ukraine have complicated the task of stemming the flow of illegal narcotics originating in Afghanistan, and there must be further discussion in the global community about the dangers posed, and possible solutions.

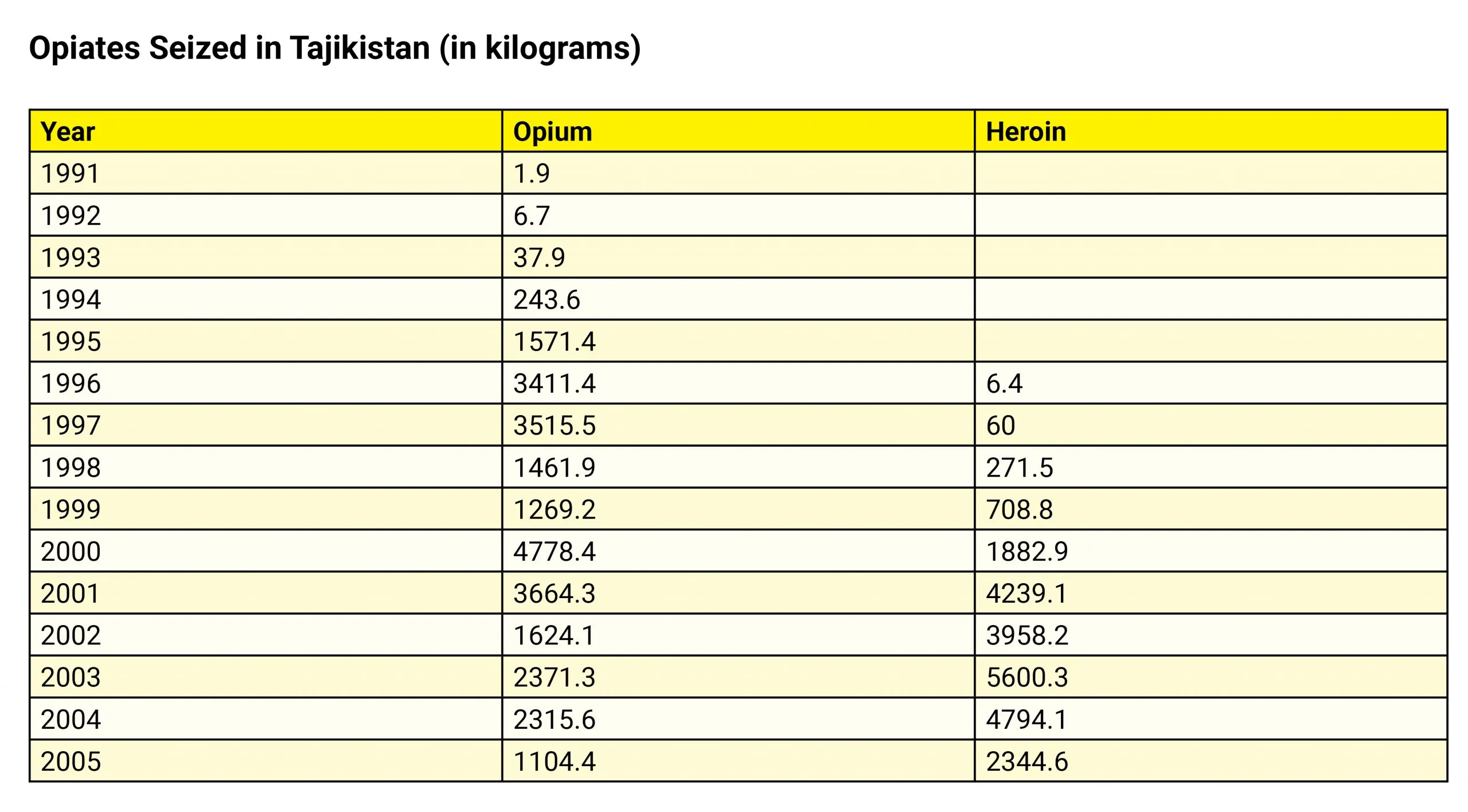

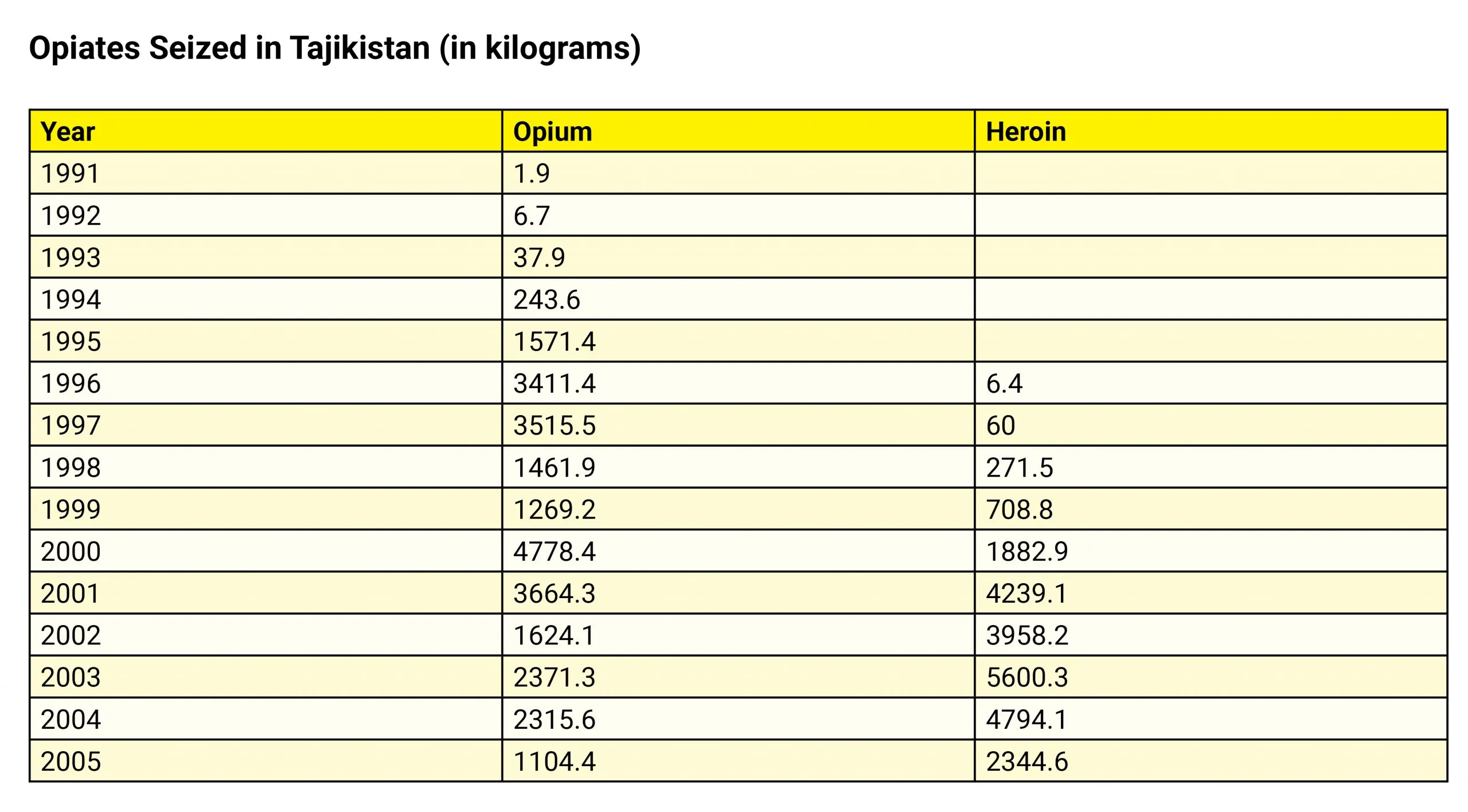

Source: DCA, 2004; UNODC, 2007

Source: DCA, 2004; UNODC, 2007

A historical background

Historically, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Eastern Iran formed the “Golden Crescent”, one of Asia’s two principal areas of illicit opium production (the other being the Golden Triangle). There have always been multiple routes for traffickers to smuggle illicit opium and other narcotics from Afghanistan along the prominent Silk Road. This is the way it has been for hundreds of years and is the case even today. One of these major routes leads through the Central Asian nations to Russia and through Belarus, into the wider European market. The fall of the secular government in Kabul in 2021 signified the failure of two decades of American and NATO presence. The Costs of War Project conducted by the Watson Institute at Brown University, had estimated that the war in Afghanistan

had cost the United States(US) US $2.3 trillion. The US alone spent over US

$8 billion from 2012 to 2017 on just trying to eradicate the Afghan Poppy, according to a report by SIGAR. To achieve their goals, they believed they needed to eliminate the Taliban’s financing, much of which came from illegal opium harvesting and trafficking.

The fall of the secular government in Kabul in 2021 signified the failure of two decades of American and NATO presence.

In late 1999, the Taliban issued a ban on poppy cultivation that resulted in the largest reduction of opium poppy cultivation in a country in any single year. Cultivation fell from an estimated

82,172 hectares in 2000 to less than 8,000 in 2001. However, the political cost to the Taliban was substantial. The ban did not last long and the Taliban rescinded the ban in September 2001, arguing they needed the financial resources to fight the US. After the stabilisation of the coalition-backed government in Afghanistan in the late 2000s and early 2010s, the government in Kabul was able to look at more issues, including the massive poppy cultivation. Some fields were burnt and large-scale seizures were carried out, and yet multiple routes of drug trafficking remained active. Though the US and NATO-backed forces continued to engage in operations to destroy the illegal narcotics infrastructure as it were, it could never completely eradicate poppy from Afghan fields. Now that the Taliban have returned to power, they have

reinstated the ban on the cultivation of poppies, and the production, use and transportation of other narcotics. We cannot say with certainty how successful they will be; however, we also cannot say with certainty how successful they want to be, considering how some in the Taliban were still using opium to fund their insurgency right until the American withdrawal from Kabul at the least.

Mapping “highways”: Trafficking routes for illicit drugs

The so called

“Northern route” from Afghanistan through Central Asia into Russia and Eastern Europe

has historically been utilised for narcotrafficking (though the legality of substances through history are debatable), becoming an important route for various parties pushing Afghan heroin into Europe. According to the UNODC, in 2010, around

15 percent of all opiates, and 20 percent of all heroin from Afghanistan was trafficked through Tajikistan. The truth is that no one knows how much Afghan heroin even goes through Tajikistan and the other Central Asian republics; there are no strong methodologies for creating such estimates. However, through the concerted efforts of the UNODC and various governments in partnership with Central Asian countries, the route leading through Central Asia has been, though not insignificant, controlled since the inception of the

Paris Pact Initiative in 2003. There have been varying levels of success and failure for the many Central Asian nations, and it remains overshadowed by other routes, including the primary “Balkan Route”. Turkmenistan, uniquely, has been a destination country for Afghan opiates being smuggled to Europe

through the Balkan route, so it is fair to say Central Asia’s role even here must not be overlooked.

Associated risks

Despite the ban, the situation in much of this region looks dangerous. Yury Fedotov, the Executive Director of the UNODC in 2010 said that

Tajikistan was the first line of defence in stemming the flow of drugs from Afghanistan. The Tajik Border Forces that are responsible for patrolling the border with Afghanistan

lack the human and technical means to effectively intercept the majority of narcotics being smuggled. Their meagre salaries make them susceptible to corruption, and their inadequate resources mean that they have little option if threatened by powerful narcotics traffickers who have no qualms about using violence or force to achieve their objectives.

Authoritarian and corrupt states have bred the narcotrafficking industry in the Central Asian region. The value of narcotics trafficked through Tajikistan in 2011 was estimated at US $2.7 billion, far exceeding any source of legitimate wealth in the country. Such a valuable industry cannot exist without significant patronage from within the government and governmental institutions. In 2004, for example, former opposition commander Akhmad Safarov was accused of drug dealing

and fled the country following a police siege. In 2008, Nurmahmad Safarov and Suhrob Lagariev, relatives of prominent Popular Front commanders,

were arrested in a major drug raid in the southern city of Kulob. The US is not free from blame here either, the majority of the trafficking in Tajikistan is believed to occur on the country’s few good roads and bridges—one of which was built in 2009 with US

$35 million in the US Central Command funds.

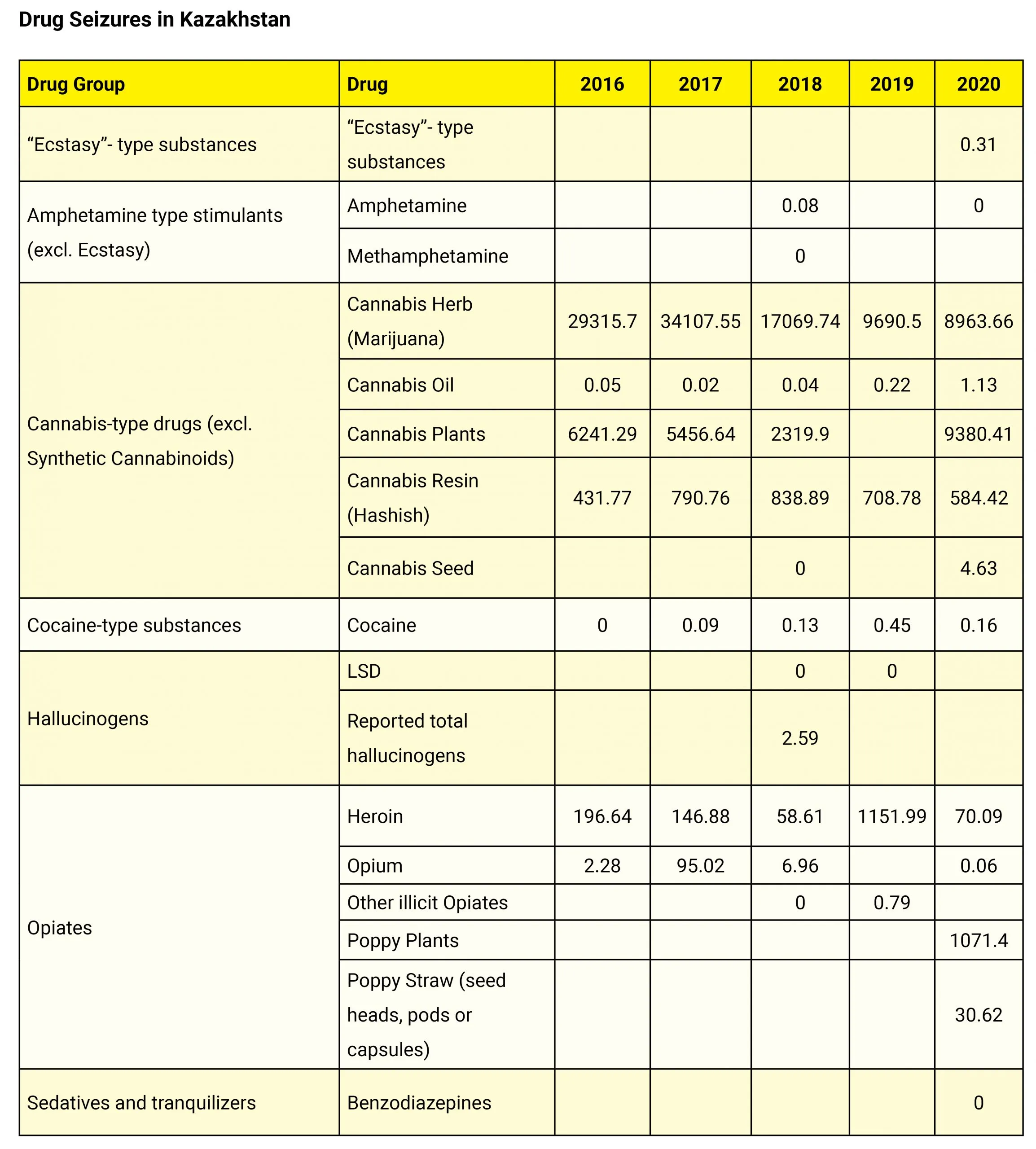

The Eurasian Economic Union agreement between Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus could be misused to circumvent counter-narcotic efforts, member states must include measures that increase security while not hampering the flow of goods.

Due to the

unrest in Kazakhstan in January of 2022, dissent has been cracked down on throughout the region. The UNODC’s threat assessment for the region in 2012 contested that in a similar situation a decade ago, resources that could be used to counter narcotics trafficking were being diverted to supress the people. The UNODC has spent considerable time and resources, developing various agreements and initiatives such as the Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination

Centre for Combating Illicit Trafficking of Narcotic Drugs, Psychotropic Substances and their Precursors (CARICC), to combat the threat of drug trafficking in Central Asia to prevent it turning into a full-blown crisis. Despite this, in the coming days, it looks like it will require more attention and backing to just maintain the status quo in the region. The Central Asian Countries and Russia should begin considering new regional and national drug policies to effectively counter this threat before it grows. The Eurasian Economic Union agreement between Russia, Kazakhstan, and Belarus could be misused to circumvent counter-narcotic efforts, member states must include measures that increase security while not hampering the flow of goods. The nations must also recognise that prohibitive measures are not enough. They must build national competencies to counter narcotics trafficking as well as drug abuse. They should also invest in better programmes for drug rehabilitation and attempt pilot programmes to prevent the re-use of needles which has already led to a dangerous

HIV Epidemic in the region. Borders must be strictly checked for narcotrafficking, and criminal groups and cells must not be allowed to gain a foothold, especially in the far-flung border regions. Many European nations are involved in capacity building in the region, yet it is highly likely that due to the region’s proximity to and close ties with Russia, nations such as Germany could decide to pull funding from programs such as the

“Central Asia Drug Action Programme” (CADAP 6), and choose to refocus that investment somewhere else.

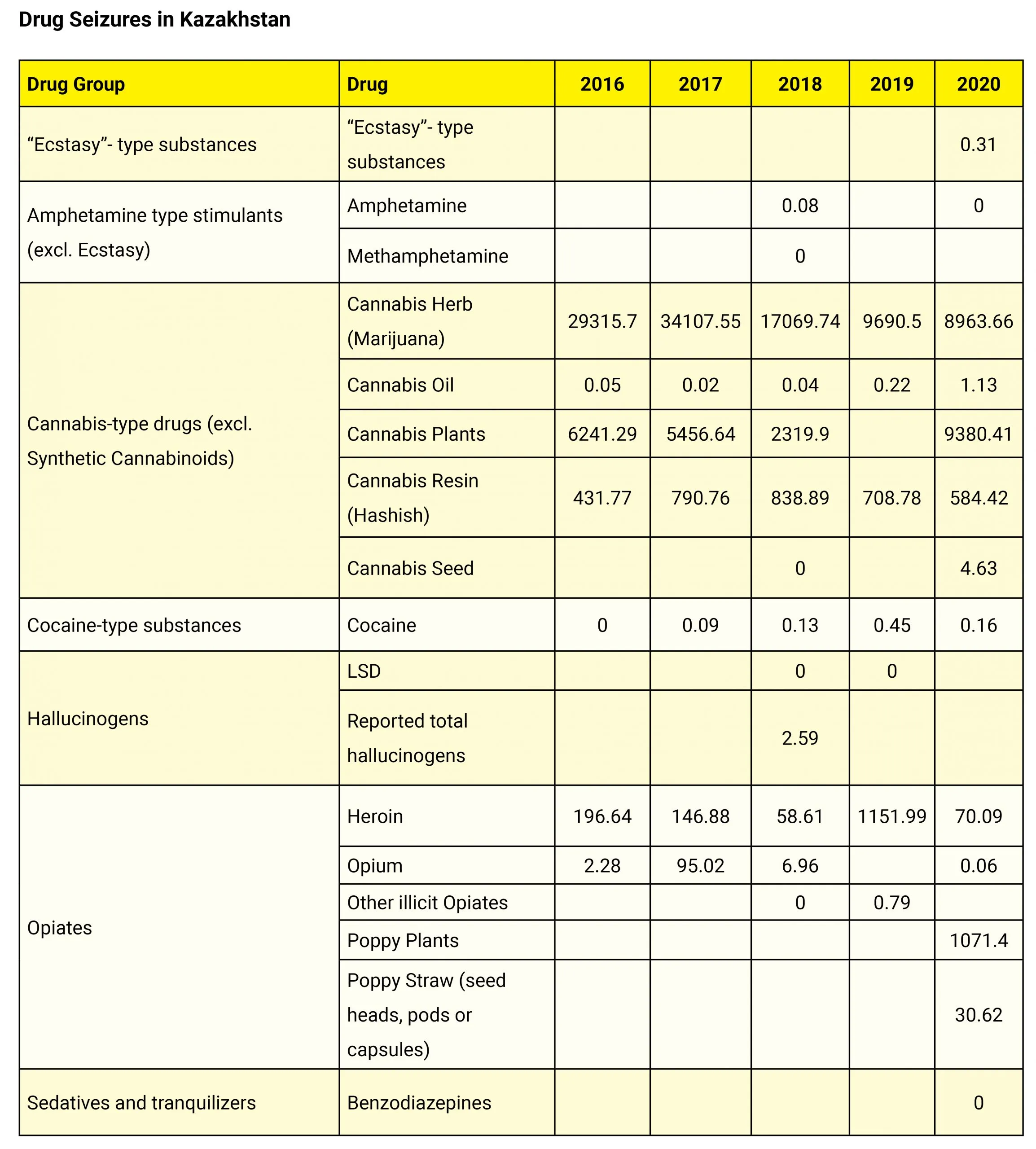

Source: https://dataunodc.un.org/dp-drug-seizures

Source: https://dataunodc.un.org/dp-drug-seizures

Russia

This already unstable situation is further impacted by the Ukrainian crisis. This has led to a large number of western sanctions to target large banks, oligarchs, and Putin’s close aides. This has also meant a large number of western companies from diverse industries such as tech, fashion, finance, and even shipping have taken action to support these sanctions, and are either

halting or ceasing major operations throughout Russia. Apart from the fact that this is leading to the loss of thousands of jobs, it could also lead to the resurgence of Russia as the piracy capital of the world, and could fuel the return of organised crime in Russia on a large scale controlling a black market for western goods. The excessive government spending on the military has resulted in funds being diverted from other important programmes, such as those which counter narcotics trafficking. Studying the human cost of such economic collapse through the eyes of drug policy, it can be assumed that if the situation continues to deteriorate, some individuals may take to a life of crime to financially support themselves and others may just end up as users of harmful drugs to escape from their painful realities. Russia has historically suffered from one of the highest rates of alcohol abuse, which if combined with a heroin epidemic could spell a recipe for social disaster. The pandemic has already led to a sharp rise in recorded deaths due to drug-related causes in Russia.

According to Russian government statistics 2016 to 2018, between 4,400 and 4,800 people died from drugs in Russia per year, however in 2020, 7,316 people died from drug overdoses. The mental and economic hardship due to the pandemic resulted in a sharp increase of nearly 60 percent in recorded deaths due to drugs. The Russian government must consider this issue a priority to ensure the health and safety of the entire nation.

Apart from the fact that this is leading to the loss of thousands of jobs, it could also lead to the resurgence of Russia as the piracy capital of the world, and could fuel the return of organised crime in Russia on a large scale controlling a black market for western goods.

Conclusion

The UNODC says that three of the last four years have witnessed the highest levels of opium production in Afghanistan. Even as the COVID-19 pandemic raged,

poppy cultivation soared by 37 percent in 2020. Despite the clear message from the UNODC, the international community has not invested nearly enough in infrastructure to counter narcotics trafficking in central Asia, considering its importance as a central node to drug trafficking throughout Europe and Asia. It is with this understanding governments must move forward with a renewed focus on countering illegal narcotics trafficking through Central Asia.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

In 2021, the head of the Tajik Drug Control Agency was cited by TASS News as having said that the volume of intercepted heroin and hashish had doubled over the last year, from

In 2021, the head of the Tajik Drug Control Agency was cited by TASS News as having said that the volume of intercepted heroin and hashish had doubled over the last year, from

PREV

PREV