This article is a chapter in the journal — Raisina Files 2023.

The impacts of climate change are already being felt in every region of the world, with the most acute effects in low-income countries.<1> Extreme weather events are increasing in frequency and intensity, putting more people’s lives, welfare, and livelihoods at risk.<2>

To mitigate climate change—indeed, for the survival of humanity—the imperative is to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG)s. In parallel to rapidly decarbonising, adaptation initiatives are equally critical for assisting individuals and communities already facing the life-changing impacts of climate change. This is especially needed in low-income countries disproportionately confronted with more frequent extreme weather events and the resulting pressures on incomes and consumption, health and safety, access to food, health, and security.

This article explores, using a gender perspective, the increasing use of digital technologies in flood mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. Today, some 1.8 billion people are at significant risk of floods,<3> most of them in low-income countries.<4> Over the last two decades alone, floods accounted for 43 percent of climate disasters and affected at least 2 billion people.<5>

Progressively, digital technologies and tools are being deployed by national and local governments, communities, and individuals to mitigate, prepare for, respond to, and recover from flood events. The way these technologies are designed, used, implemented and evaluated have significant implications for gender parity.

Gender and Floods

Climate shocks such as floods affect people in different ways and can exacerbate existing inequities.<6> Often, women and girls face greater exposure,<7> owing to various factors including patriarchal power structures, social norms that restrict their access to information and technologies, unequal control over finance and assets, and labour market and income dynamics.<8> Women are not inherently weaker or more vulnerable; rather, social, economic, and political structures often make them so. Gender also intersects with other identities—race, age, ability, and immigration status—that together create unique vulnerabilities. It is essential, therefore, to recognise how these different dimensions of identity shape women's exposure, vulnerability, and coping mechanisms and to ensure that adaptation efforts adequately respond to women’s diverse experiences.

Four times as many women as men in India, Indonesia, and Sri Lanka died during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.<9> The higher mortality among women was partly because women were more likely to stay behind to care for children and others in need, because more women were at home or near the sea when the tsunami hit, and women were less likely to know how to swim.<10> During the 2007 tsunami in Somoa and Tonga, 70 percent of the adults who died were women.<11> To be sure, however, this will not always be the case, as gender interacts with other factors like income, resources, and opportunities to determine vulnerability.<12>

Safety is also an essential concern for many women during and after weather events, informing their decisions about when and whether to evacuate. For example, during the floods in North East Bangladesh in June 2022, shelters housing some of the 7.2 million affected people did not have separate WASH facilities (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) or spaces for women and girls that could provide them security and protection.<13> Perceptions and experiences of safety in such public spaces are essential in informing women's decisions about where it is safe to seek shelter. Moreover, gender-based violence poses particular threats to women during crises.<14> Across 19 countries, researchers found that drought spells are associated with increased inter-partner violence against women.<15> After two cyclones in Tafea, Vanuatu, cases of domestic violence increased by 300 percent.<16> A study of inter-partner violence in the United States before and after Hurricane Katrina, found that the incidence of violence against women nearly doubled after the storm, from 4.2 percent of women to 8.3 percent.<17>

Education is also interrupted for those impacted by flooding. Even when floods have receded, children often remain outside school to help their families in recovery, and schools remain damaged or else utilised as shelters. Half of the schools in Vanuatu were closed for a month in 2015 due to Cyclone Pam.<18> In the same year, more than 4,000 schools were damaged, and more than 600 were destroyed during Cyclone Komen in Myanmar.<19> Some years earlier, the devastating floods in Pakistan in 2010 led to the closure of 8,000 schools and the transformation of an additional 5,000 into shelters.<20>

Girls' education tends to be disrupted for longer periods of time during climate shocks, compared to boys’. The destruction of education facilities, damaged transportation infrastructure, family financial burdens incurred from the disaster, and unavailability of rehabilitated WASH facilities in schools, among other factors, do not impact children equally.<21> After the floods in Pakistan in 2022, for example, a third of parents reported that it would be more difficult for their female children to return to school.<22> This is because girls often carry a greater burden of unpaid and care responsibilities, which can increase during and after floods or other weather-related events. Flood impacts on household incomes can also mean fewer resources available for children to attend school, with boy children being more likely to return.

Moreover, across countries with varied levels of economic development, women often face unique insecurities before, during, and after flood events due to factors such as occupation, income, and relative lack of ownership and agency over the family’s financial assets.<23> For instance, during a disaster, financial assets in the form of savings are often critical for ensuring consumption of essential commodities.<24> However, women tend to own fewer assets than men.<25> They are also more likely to have tangible assets in the form of jewelry, expensive fabrics, or cash rather than a bank account, and those possessions are at-risk during floods.<26>

Digital Technologies for Disaster Risk Reduction and Management

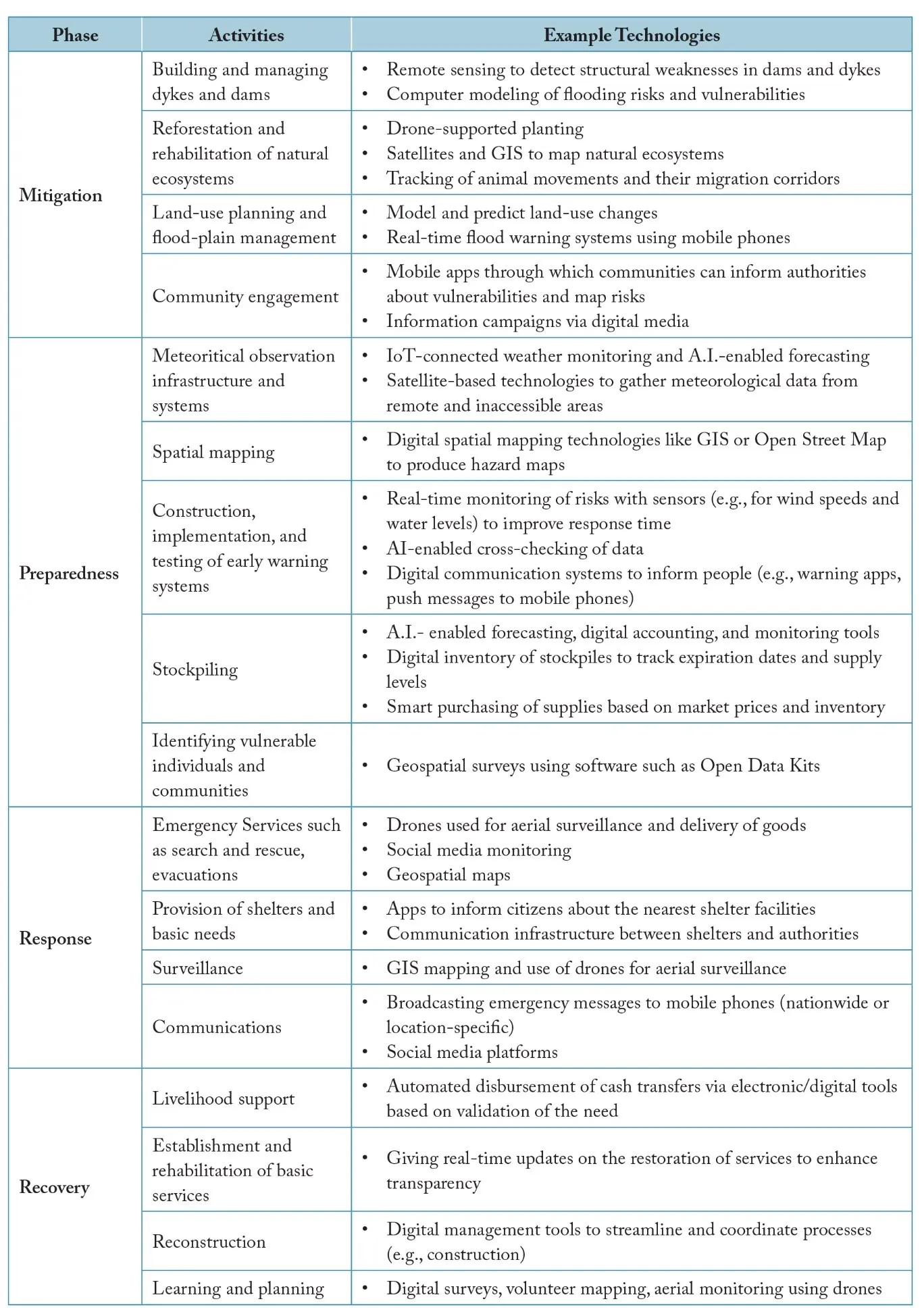

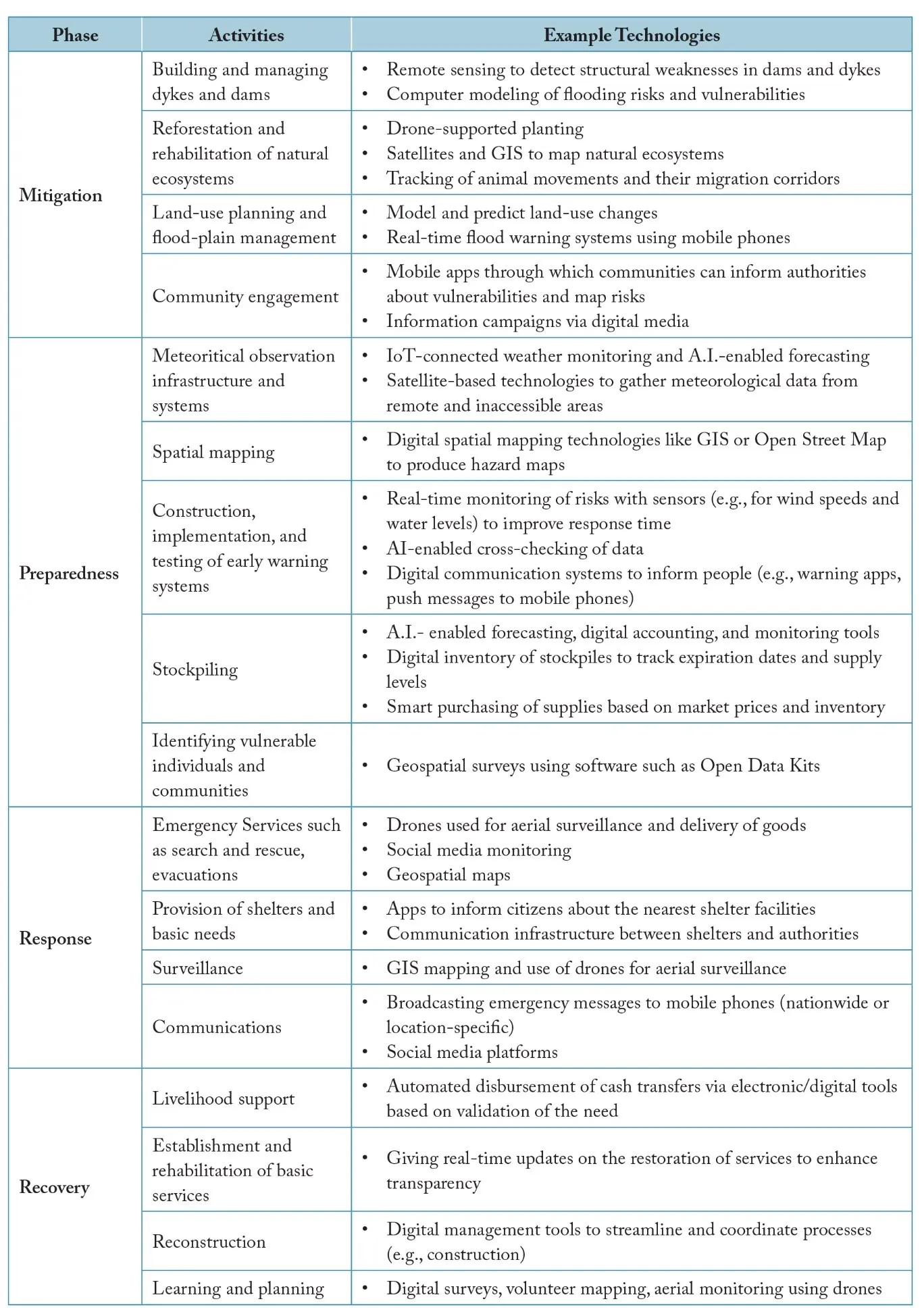

Many digital technologies and tools are used to help communities adapt to the increasing risks of flood events. Governments and organisations are working to bolster resilience using tech innovations, from geospatial mapping to IoT-enabled smart infrastructure, AI-based forecasting, and digital communications and social media. However, if not done well, the planning, design, and use of such technologies pose risks for further exacerbating gender inequalities in developed and developing countries alike.

Digital technologies offer tools for potentially more effective and timely disaster risk reduction and response, but they can also create more significant risks for girls and women, especially if they are not designed using an inclusive and participatory approach that takes into account gender-specific experiences, needs, and perceptions. Moreover, the lack of access to information and communication technologies among women hampers access to critical information, services, and support. It is crucial to ensure that the use of digital technologies in DRM are gender-inclusive and respond to the unique vulnerabilities faced by women and girls, and other marginalised populations. Table 1 provides examples of digital technologies used in different phases of flooding DRM.

Table 1: Key Technologies for DRM in Flooding

Source: Author’s own, using various open sources.

Source: Author’s own, using various open sources.

Innovations and new applications of digital technologies are transforming flood mitigation and preparedness, response, and recovery efforts. For example, disasters can cause immediate and long-term food insecurity. The World Food Program (WFP) developed a mobile vulnerability analysis and mapping (mVAM) program which allows them to collect household survey data on food security situations via phone calls, SMS, and voice response.<27> The household food security data is uploaded to the HungerMap website, which provides real-time information to inform program and emergency response efforts.<28>

Online flood risk and hazard maps can be vital for making informed investment decisions, such as where to settle or start a business. Many geospatial mapping tools, such as ArcGIS and OpenStreetMap, are used to collect data and disseminate information about the spatial allocation of hazards such as flooding.<29> One example is Nusaflood, created by a women-led team in Indonesia. Nusaflood provides an easily accessible spatial visualisation tool that maps future flooding risks. The tool was designed to help people (even those with limited digital technology skills) make informed decisions about where to live, invest, and work in Indonesia with future flooding risks information at hand.<30>

Websites and apps with real-time weather and storm-related information, such as weather forecasts, severe weather-impacted areas, and evacuation routes, are critical for planning and decision-making in the event of a weather event. Cities and national governments are also investing in various hydrological and meteorological monitoring infrastructures and systems to forecast and monitor such events.<31> Many such systems involve remote sensors, IoT-connected devices, and A.I.-based weather models used for forecasting.

With the onset of a flood, early warning systems (EWS) are important for disseminating information to the population about events monitored through such systems. EWSs use applications and text messaging to send alerts and warnings. EWS information must be collected and disseminated in an appropriate, timely, and applicable way and this information should reach the most disadvantaged communities.<32> When early warning systems are not designed with diverse end-users in mind, especially the most vulnerable, they exacerbate the risks of flooding hazards. For instance, after the floods in Pakistan in 2010, the government established an early warning system in the Lai Basin.<33> However, an assessment of the EWS found that it failed to engage the relevant communities in its design and that the key risk messages needed to be more easily understandable and aligned with different perceptions of flood risk among the population.<34> Moreover, EWSs often transmit information through channels that are more accessible to male audiences,<35> delaying women’s access to that information.

Some initiatives are underway to address gaps in information about unfolding weather events. For example, the Women's Weather Watch (WWW) was established in Fiji after the 2004 floods.<36> WWW started a bulk SMS system, radio station, social media pages, and messaging apps to disseminate real-time, understandable information about weather events.<37> WWW specifically targets their information to rural women.<38>

Other applications such as the Trilogy Emergency Response Application (TERA) allow two-way communication between affected people and responders.<39> Meanwhile, the WFP created Mila, an AI-based chatbot that provides people in Libya with information about humanitarian services.<40>,<41>

Finally, digitally enabled platforms and apps are used in recovery. For instance, digitally enabled transfer systems allow for rapid identification of people in need, and the deployment of cash transfers.<42> In the aftermath of a flood event and during recovery, mobile technologies can be crucial for accessing financial resources and critical digital documents such as proofs of identification, deeds, health records, or visas.

While remarkable progress has been made in developing and applying digital technologies for planning, responding to, and recovering from flood events, a gender-responsive approach is crucial for ensuring that they do not replicate and deepen existing inequities. Strategies could include the following:

Engagement of women and girls at all stages of technology design, iteration, planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Increasing access and ownership of digital devices such as smartphones, as well as enhancing access to and use of the internet among women and girls.

Ensuring that EWSs are responsive to gender differences in perceived risks, messaging, decision-making, vulnerability, and social norms.

Promoting the use of low-tech solutions where relevant. While digital and advanced technology solutions are often exciting, recognising when low-tech solutions are more effective and efficient is critical.

Recognising and responding to the preferences, needs, and capabilities of women with intersectional identities and vulnerabilities.

Leveraging digital tools where appropriate to enhance access to social protections, insurance, digital documents, and digital banking among women.

Generating and analysing gender-disaggregated evidence about new digital technologies and tools to evaluate their impacts on gender-transformative DRM.

Building back better by ensuring that recovery initiatives are gender-inclusive and promote and support gender equity across domains.

As the impacts of climate change increase in frequency and intensity, adaptation efforts are crucial. Flooding poses a significant risk to communities around the world, and as countries, cities, and communities work to mitigate and prepare for flood events, digital technologies offer immense potential. However, they could also deepen gender inequities, leaving women and girls more at risk from the severe impacts of flood events. It is important that technology firms, international organisations, governments, humanitarian organisations, and communities take a gender-transformative approach as they make disaster readiness plans. This will ensure the equitable inclusion of women and girls and enable their full participation in decision-making, planning and response.

Endnotes

<1> H.-O. Pörtner, et al., Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp., doi:10.1017/9781009325844.

<2> Pörtner, et al., Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability

<3> Jun Rentschler, Melda Salhab, and Bramka Arga Jafino, “Flood Exposure and Poverty in 188 Countries,” Nature Communications 13, no. 1 (June 28, 2022): 3527, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30727-4.

<4> McDermott, Thomas K. J. “Global Exposure to Flood Risk and Poverty,” Nature Communications 13 (June 28, 2022): 3529. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30725-6.

<5> Pascaline Wallemacq and Rowena House, Economic Losses, Poverty & Disasters: 1998-2017, UNDRR, 2018. https://www.undrr.org/publication/economic-losses-poverty-disasters-1998-2017.

<6> United Nations, World Economic and Social Survey 2016: Climate Change Resilience: An Opportunity for Reducing Inequalities, United Nations, 2016.

<7> UN Women, “Explainer: How Gender Inequality and Climate Change are Interconnected,” UN Women, 2022.

<8> Sonja Ayeb-Karlsson, “When the Disaster Strikes: Gendered (Im)Mobility in Bangladesh,” Climate Risk Management 29 (January 1, 2020): 100237, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2020.100237.

<9> Rhona MacDonald, “How Women Were Affected by the Tsunami: A Perspective from Oxfam,” PLoS Medicine 2, no. 6 (June 2005): e178, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0020178.

<10> Oxfam, The Tsunami’s Impact on Women, Oxfam, 2005, .https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/115038/bn-tsunami-impact-on-women-250305-en.pdf

<11> Kate Morioka, Time to Act on Gender, Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction, UN Women (Bangkok, Thailand), 2016, p.23.

<12> Eric Neumayer and Thomas Plümper, “The Gendered Nature of Natural Disasters: The Impact of Catastrophic Events on the Gender Gap in Life Expectancy, 1981–2002,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 97, no. 3 (September 1, 2007): 551–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00563.x.

<13> U.N. Women, Rapid Gender Analysis of Flood Situation in North and North-Eastern Bangladesh: Gender in Humanitarian Action Working Group, U.N. Women, June 2022, https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2022-07/bd-Rapid-gender-analysis-north-northeaster-flood-2022.pdf

<14> Kim Robin van Daalen et al., “Extreme Events and Gender-Based Violence: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review,” The Lancet Planetary Health 6, no. 6 (June 1, 2022): e504–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00088-2.

<15> Adrienne Epstein et al., “Drought and Intimate Partner Violence towards Women in 19 Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa during 2011-2018: A Population-Based Study,” ed. Lawrence Palinkas, PLOS Medicine 17, no. 3 (March 19, 2020): e1003064, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003064.

<16> Morioka, Time to Act on Gender, Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction

<17> Julie A. Schumacher, et al., “Intimate Partner Violence and Hurricane Katrina: Predictors and Associated Mental Health Outcomes,” Violence and Victims 25, no. 5 (2010): 588–603.

<18> UNICEF, It is Getting Hot: Call for Education Systems to Respond to the Climate Crisis, UNICEF (Bangkok), 2019.

<19> UNICEF, It is Getting Hot: Call for Education Systems to Respond to the Climate Crisis

<20> Zeina Khodr, “Floods Damage Schools,” Al Jazeera, August 29, 2010, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2010/8/29/pakistan-floods-damage-schools

<21> Kate Sims, Education, Girls’ Education and Climate Change, Knowledge, Evidence and Learning for Development, March 2021.

<22> Freya Perry, Izza Farrakh, and Elena Roseo, “Invest in Human Capital, Protect Pakistan’s Future,” World Bank Blogs, January 26, 2023, https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/invest-human-capital-protect-pakistans-future.

<23> Morioka, Time to Act on Gender, Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction

<24> World Bank, Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Disaster Recovery, World Bank, Washington, DC, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1596/33684.

<25> Alvina Erman et al., Gender Dimensions of Disaster Risk and Resilience: Existing Evidence, World Bank, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1596/35202.

<26> Alvina Erman, et al., Gender Dimensions of Disaster Risk and Resilience: Existing Evidence

<27> World Food Program, Vulnerability Analysis and Management: Food Security Analysis at the World Food Program, World Food Program, 2018, https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000040024/download/

<28> World Food Program, “Women as Shock Absorbers: Measuring Intra-Household Gender Inequality,” World Food Program MVAM The Blog, 2022. https://mvam.org/

<29> Ian McCallum et al., “Technologies to Support Community Flood Disaster Risk Reduction,” International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 7, no. 2 (June 1, 2016): 198–204, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-016-0086-5.

<30> Sarah Brown, et al., “Gender Transformative Early Warning Systems: Experiences from Nepal and Peru,” Practical Action, 2019, https://wrd.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/GENDER~1_1.PDF

<31> Asian Disaster Reduction Center, “Total Disaster Risk Management: Good Practices”.

<32> Brown, et al., “Gender Transformative Early Warning Systems: Experiences from Nepal and Peru”

<33> Daanish Mustafa et al., “Gendering Flood Early Warning Systems: The Case of Pakistan,” Environmental Hazards 14, no. 4 (October 2, 2015): 312–28, https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2015.1075859.

<34> Mustafa et al., “Gendering Flood Early Warning Systems: The Case of Pakistan”

<35> Intergovernmental Authority on Development, “Regional Strategy and Action Plan for Mainstreaming Gender in Disaster Risk Management and Climate Change Adaptation,” IGAD, 2020, P.5.

<36> ActionAid, “Innovation Station: Women’s Weather Watch, Fiji,” ActionAid, https://actionaid.org.au/articles/innovation-station-womens-weather-watch-fiji/

<37> ActionAid, “Innovation Station: Women’s Weather Watch, Fiji”

<38> “Women and ICT Access: Bridging the Digital Divide for Disaster Resilience,” Data-Pop Alliance, November 13, 2022, https://datapopalliance.org/women-and-ict-access-bridging-the-digitial-divide-for-disaster-resilience/.

<39> South East Asia’s Road to Resilience, “Trilogy Emergency Response Application”.

<40> World Food Program, Vulnerability Analysis and Management: Food Security Analysis at the World Food Program

<41> Suzanne Fenton, “A Chatbot Named Mila: Answers the Call for People in Lybia,” The World Food Program, 2021.

<42> IMF, Digital Solutions for Direct Cash Transfers in Emergencies, IMF, Washington, DC.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV