From MDGs to SDGs

Sustainable development became mainstream after the publication of the 1987

Brundtland Commission report—formally known as the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), which defined sustainable development as the “development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. This definition, which essentially advocates for intragenerational as well as intergenerational equity, was the first official attempt to delineate a new kind of development framework.

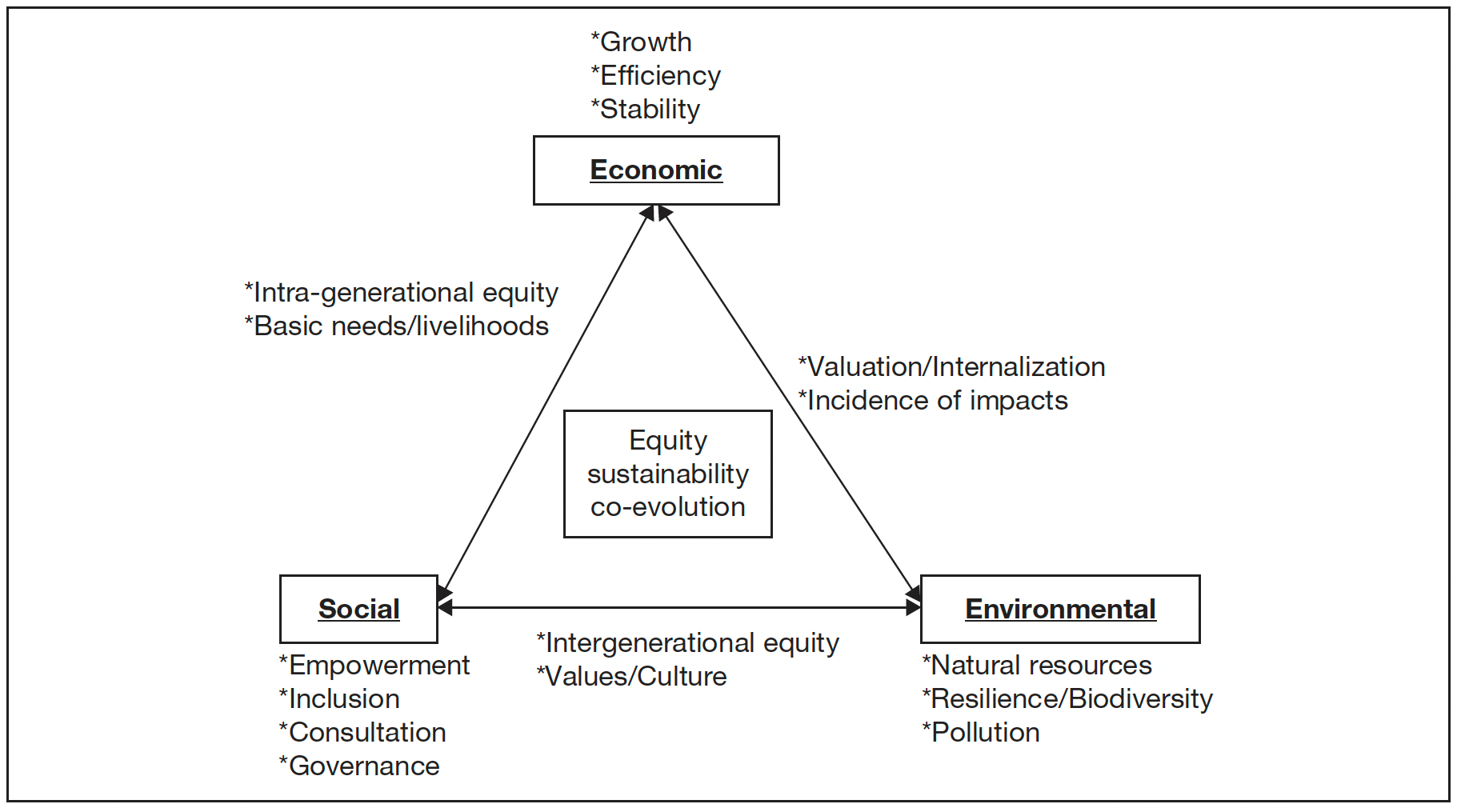

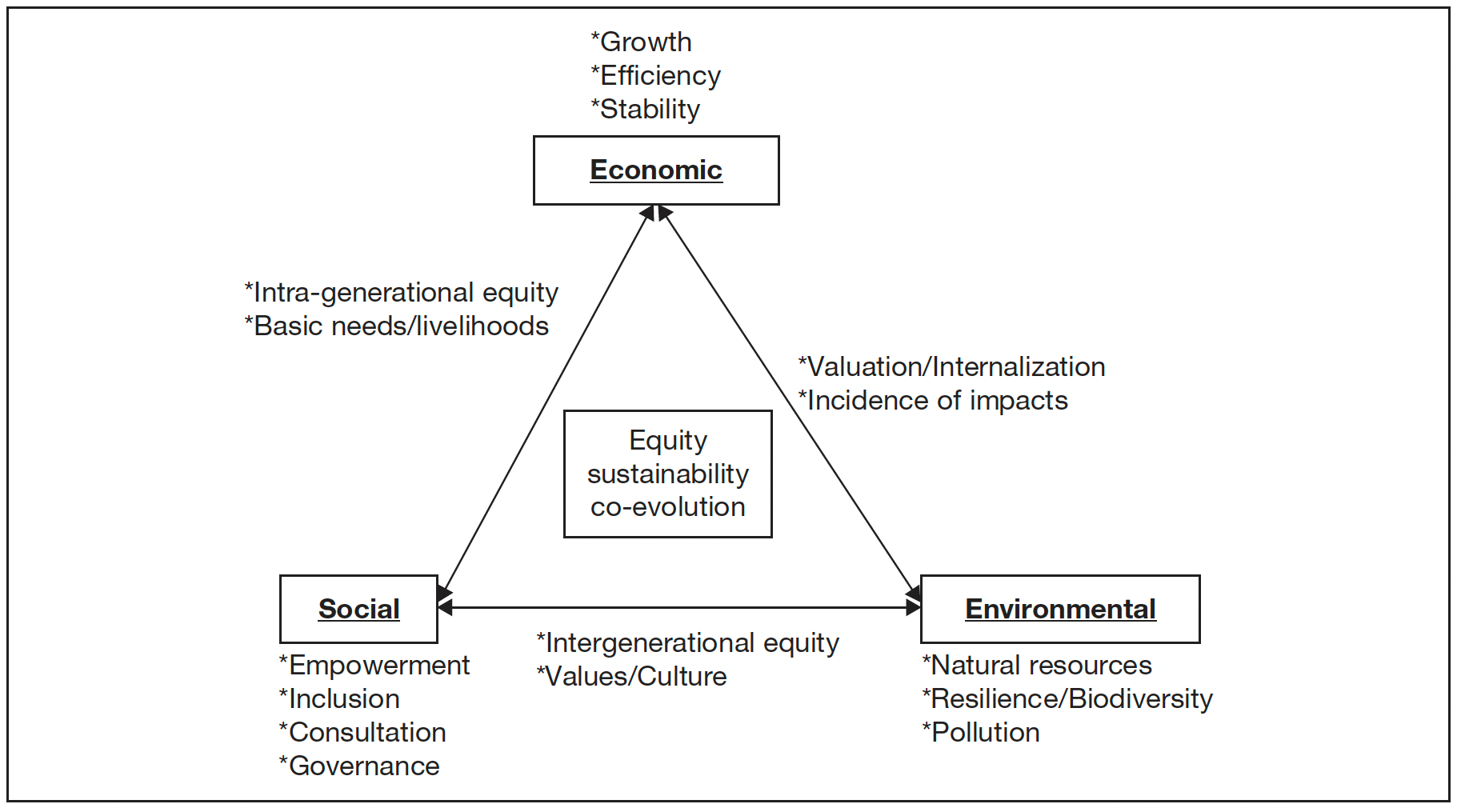

The diagram presented below (Figure 1) represents the sustainable development triangle, that Mohan Munasinghe introduced during the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. This widely accepted concept recognises the interconnectedness of three key domains–economy, society, and environment. It

asserts that environmental transformations impact institutions, culture, and economic progress both in the short and long term. Likewise, alterations in social values and behaviour can influence economic development and environmental management. Lastly, economic growth, wealth distribution, and well-being distribution affect social and ecological characteristics.

Figure 1: Elements of Sustainable Development

Source: Munasinghe, 2007

Source: Munasinghe, 2007

The

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) was a set of eight international development goals established by the United Nations in 2000 with a timeline of 15 years. They were designed to address critical global challenges such as poverty, hunger, disease, gender inequality, and other pressing issues. In addition, they highlighted the importance of

SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound) goals to monitor progress through indicators and data. As the next step, in September 2015, the UN member states adopted the 17

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with 169 targets—that aim to improve people's lives, protect the planet—enable a prosperous future for humankind through the complex interplay of advancing physical, social, human, and natural capital and vice versa.

The transition from the MDGs to the SDGs represents an evolution in understanding development challenges and the need for a comprehensive, integrated, and inclusive approach. Despite the

persistence of (economic) growth fetishism in many aspects of policy thinking in developing nations, the concept of sustainable development has gained significant prominence by connecting ecosystem services, environmental degradation, societal concerns, and quality of life to economic growth. This transformative change, occurring in less than a century, can be seen as nothing short of a revolution.

Why sustainable development?

Firstly, to address global challenges, sustainable development is a response to the pressing environmental, social, and economic challenges facing the world today, ranging from the post-pandemic macroeconomic repercussions to the impact of the Ukraine-Russia conflict on the global food and energy markets. As a result, individuals can gain the knowledge and skills needed to contribute to finding solutions for issues such as climate change, poverty, inequality, resource depletion, and environmental degradation. Secondly, the development model is now inherently interdisciplinary, drawing on fields such as environmental science, economics, sociology, political science, etc. This interdisciplinary nature offers an exploration of various academic disciplines and develops a broad understanding of complex problems.

The transition from the MDGs to the SDGs represents an evolution in understanding development challenges and the need for a comprehensive, integrated, and inclusive approach.

Third, many individuals are motivated by a desire to positively impact society and the environment, with the knowledge and tools to actively contribute to sustainable practices and policies, whether through research, advocacy, policy development, or practical implementation. And fourth, sustainable development encourages a holistic and

systems-based approach to problem-solving. It develops critical thinking skills and analysis of complex systems, understanding their interdependencies, and, most importantly, identifying leverage points for transformative change.

Beyond the Gross Domestic Product

Partha Dasgupta, Pushpam Kumar, and Shunsuke Managi, who have done some seminal work on sustainable development and the concept of inclusive wealth, suggest that the progress towards attaining

SDGs has been constrained by the lack of monitoring tools to evaluate progress. In pursuing economic growth, most developing and underdeveloped economies have primarily focused on

GDP growth and stock market performance, neglecting other metrics of progress. However, GDP growth alone does not comprehensively represent economic capabilities and development realities.

By exploiting natural resources to pursue extensive economic growth, the GDP as a measure of progress fails to consider the significance of human capital, the non-market benefits of natural resources, and the monetary assessment of positive and negative externalities. Moreover, it fails to consider environmental and social costs associated with production and income inequality, resulting in an incomplete reflection of living standards. Yet, despite awareness of these limitations, GDP continues to dominate development conversations as the sacred growth indicator. As a result, several alternative metrics to GDP have been proposed to address these limitations, including the concept of

Inclusive Wealth, which considers a country's capital asset stocks across produced, natural, human, and social capital.

The Inclusive Wealth Index (IWI) helps contrast social value with the market price of resources and could be the future of conceptually understanding sustainable development metrics.

The last

Inclusive Wealth Report 2018 by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) recommends that there is a need to migrate to measuring progress using alternate indices that are more comprehensive. The Inclusive Wealth Index (IWI) helps contrast social value with the market price of resources and could be the future of conceptually understanding sustainable development metrics. Unlike other metrics, IWI reflects current trends and past behaviour and forecasts future status, ensuring that future generations are at least as well off as the current generation.

The excessive focus on GDP growth as a metric for progress has resulted in economists advocating that technological advancements can compensate for a decline in productivity caused by the depletion of natural resources. Ecological scientists have countered this by saying that substitution possibilities among the three types of capital—natural, produced, and human—are not actually possible. Alternatively, the IWI is a

comprehensive and versatile measure of sustainable development, encompassing multiple dimensions, and targets. An increase in the IWI can contribute to various positive outcomes, including poverty eradication, enhanced food security, sustainable agriculture, healthier lives, and overall well-being.

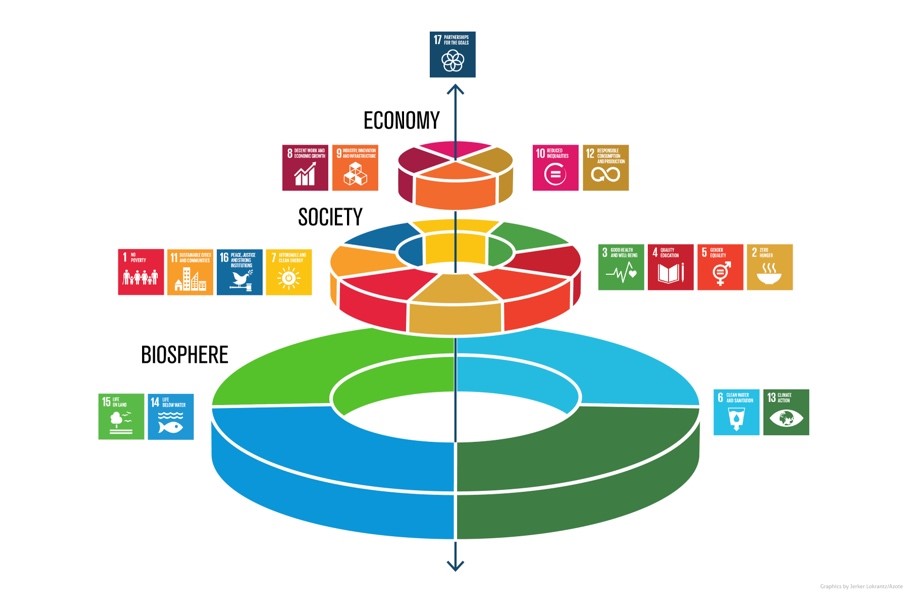

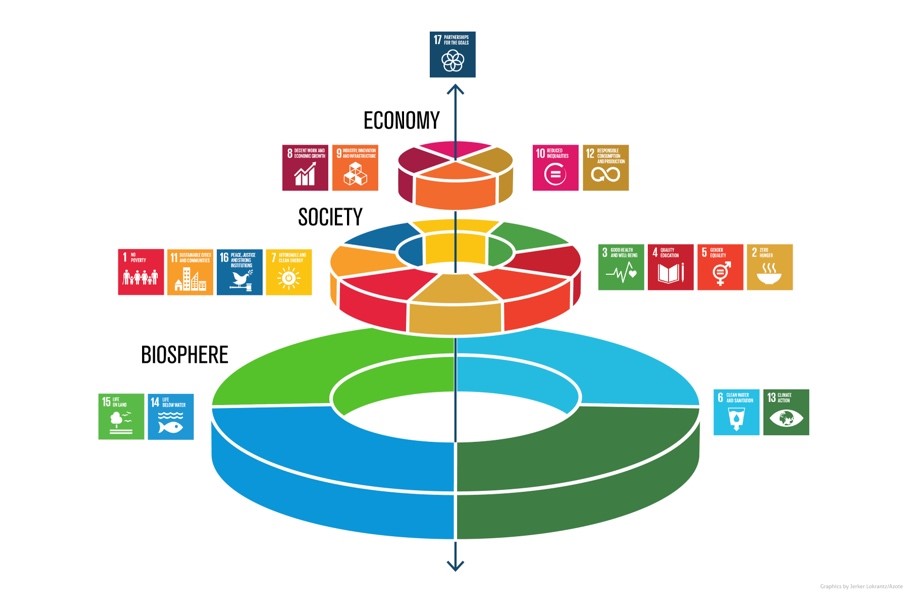

Figure 2: Inter-linkages among the SDGs

Source: Stockholm Resilience Center

Source: Stockholm Resilience Center

While sustainability science has made notable progress in highlighting the interconnectedness between sustainability's social, economic, and ecological dimensions, prevailing development practices tend to perceive these dimensions as discrete entities. Consequently, there is an inclination to prioritise socio-economic development objectives while inadvertently overlooking the associated environmental ramifications. To successfully advance the implementation of Agenda 2030, it is imperative to transcend this reductionist stance and recognise the complex interplay between human beings and the natural environment. Consequently, a fresh perspective is required, whereby the economic and social facets of the SDGs are conceptualised as integral components embedded within the biosphere, as shown above (Figure 2).

Soumya Bhowmick is an Associate Fellow with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV