-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Improving the way food is produced — and also consumed — will go a long way towards addressing global warming.

Global warming is one of the most defining challenges of our time. The global food system, which encompasses production and post-farm process such as processing, and distribution accounts for 25 percent of global Green House Gas (GHGs) emissions. At the same time, food production is also highly dependent on the natural resource base of the planet — accounting for 50 percent of habitable land use, 70 percent of freshwater use, and 78 percent of global ocean and freshwater pollution. Therefore, improving the way food is produced — and also consumed — will go a long way towards addressing global warming. Since the farm-stage in the entire agricultural value chain accounts for a predominant share of its impact on the environment, research, debate, and discussions have focussed primarily on the supply-side dynamics of the agricultural, or food, value chain. But at the same time, radical changes in the overall patterns of demand for food is also necessary. According to a recent study, technology can provide energy efficiency measures that help combat climate change, but “consumption (and to a lesser extent population) growth have mostly outrun any beneficial effects of changes in technology over the past few decades.” Understanding the factors that influence the current demand patterns for food and how to modify them to achieve outcomes that are more in harmony with the planetary boundaries is crucial for sustainable development.

With a growing population and rising income across the world, the demand for food is also exponentially increasing. Although the share of food in total consumption expenditure declines with increase in per capita incomes. But at the same time, the share of meat, dairy, oils, and fats in total food expenditure increases. Since these food products are more intensive in the use of natural resources like water, land, and emit higher GHGs, the overall impact on the environment is also higher. Ecological Footprint (EF) captures this interaction between human consumption and the biocapacity of the planet — i.e. the supply of natural resources. Recent estimates suggest that global EF has been increasing steadily at an average rate of 2.1 percent since 1961 and it has tripled to 20.6 billion global hectares in 2014 from only 7 billion global hectares in 1961. At the same time, the total biocapacity of the planet was only 12.2 billion global hectares in 2014. Implying that humanity’s EF in 2014 was already 69.6 percent greater than its capacity. Along with unsustainable agricultural production, high levels of ecological overshoot is also driven by an increase in population and per capita consumption. Scientists’ have warned that affluence is a major systematic driver of overconsumption and its impact on the environment. Not only are the people in the top income percentiles driving this consumption trend and environmental impact, they are also influencing social norms regarding consumption for the rest of the population. For instance, positional consumption is largely driven by aspirations with everyone striving to be “superior” relative to their peers while the overall consumption level rises.

Against this backdrop of rising consumption demand for food, depleting natural resources and global warming induced climate change, what is it that consumers can do to induce ecologically sustainable consumption? According to Keynesian economics, it is demand that drives production and the economy. Therefore, making right food choices can play an important role in increasing the demand for sustainable products. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have already highlighted the importance of ‘responsible consumption’ as a key strategy towards ensuring a safe and secure planet for all by 2030. However, despite the rising trend of sustainable consumerism the market share of products that are ‘sustainable’ is still very low. Therefore, consumers are still not engaging in the purchase of products that are more sustainably produced. This does not, however, necessarily imply that consumers are not ecologically or environmentally sensitive.

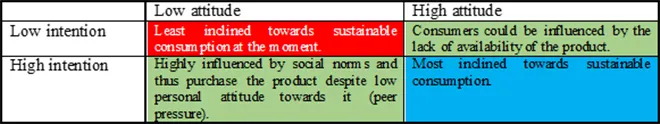

A post-modern consumer is increasingly characterised by a more responsible and exigent buyer behaviour, more attentive to the ‘mode of production’ of food and the impact of their actions in solving a problem — in this case environmental degradation. But when it comes to actual purchasing, a clear inconsistency between attitudes towards sustainable consumption and actual behaviour is observed. This phenomenon is called the attitude-behaviour gap (ABG). For example several surveys have shown that 30 percent to 50 percent of consumers indicate their intention to buy sustainable products. Yet, the market share of these goods is often less than 5 percent of the total sales. This ABG can be attributed to several factors that influence the decision-making process of a consumer. Unlike traditional economic theories based on rationality, human decision making is not guided by a stable and consistent utility structure. As Daniel Kahneman has put it aptly in his book Thinking Fast and Slow, “it is self-evident that people are neither fully rational nor completely selfish, and that their tastes are anything but stable.” Another fellow economist Richard Thaler got the Nobel prize in 2017 for showing that humans are not always rational, but a little nudge can push them in the right direction. It depends upon the choice structure that an individual faces. Final behavioural intent is determined by an interplay of values, needs, motivations, knowledge, and information, availability of the products and Perceived Consumer Effectiveness (PCE). PCE refers to the impact that a consumer believes her action will have in solving the problem. Higher PCE will lead to more positive attitudes towards purchasing sustainable products, and vice versa. Studies on behavioural responses towards sustainable products have revealed four categories of consumers based on the attitude-behaviour parameters. Attitude refers to their predisposition, either positive or negative, towards the sustainable characteristics of the product, say its low carbon footprint, while behaviour corresponds to whether they would actually purchase the product, i.e. support their attitude with intent.

Source: Based on Vermeir and Verbeke (2006)

Source: Based on Vermeir and Verbeke (2006)Consumers exhibiting low attitude-low intent (red box) and high attitude-high intent (blue box) have consistent preference and behavioural patterns as their attitude and intent towards sustainable consumption is aligned. However, consumers represented by the green boxes are the ones that exhibit the ABG phenomenon. The consumers either have a positive attitude towards sustainable consumption but are unable to purchase due to factors like unavailability of the product, higher price, lower Perceived Consumer Effectiveness; or they purchase the product despite having a low attitude towards it. The latter is driven by social norms and the willingness to comply with the opinions of others. For those least inclined towards sustainable consumption, information emphasising on personal benefits of sustainable consumption and increasing their relevance to the consumer — for instance, in terms of health benefits — can be a possible way of changing their behaviour, or nudging them towards sustainable consumption. Similarly, consumers in the top right corner (high attitude-low intent) are most likely to be converted into sustainable consumers because they have a very positive attitude. Perhaps, lack of information on the availability of the product, or a lower PCE can be a major factor hindering their action to purchase the product, despite sufficient desire to do so. Another major factor which has a negative impact on the final purchase decision of consumers is the relatively higher price of the products themselves. Addressing this would require major changes in the production of food products such that the social and environmental costs of production are accounted for in the final price of the products. The higher price for organic, ‘green’ or sustainable products is essentially due to efforts made to internalise the social and environmental impacts in the costs of production. As long as this is not considered across industries and sectors, the price of sustainable products will continue to remain relatively higher.

Notwithstanding supply-side interventions, there are societal, personal, and situational factors that influence final consumption intent. But these factors are not uniform across groups or even within a group of people. A survey based on behavioural and experimental economics techniques will help identify the major factors that influence different decisions regarding sustainable food consumption. Identification of specific gaps or patterns of consumption vis-à-vis the various social, personal, and situational factors will help create nudges that can be used to manipulate the outcomes. Furthermore, using nudges is advantageous over classic informational campaigns and education because they require lesser cognitive effort, are unobtrusive in nature and also less costly. This makes it easier to improve food choices of consumers by altering the choice environment. For example, the way products are positioned, their visibility or packaging can significantly change consumer behaviour. To begin with, nudges must be targeted at those who are most likely to respond — for example, people in the top right-hand corner of the ABG matrix. Such mechanisms have already been used to improve political outreach during campaigns and influence voter decisions. Why not do the same for the greater good of the planet?

Concerted efforts towards changing consumption patterns is complementary to the efforts at improving agricultural production. The two must work in tandem to ensure a safe and secure planet for all.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Roshan Saha was a Junior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation Kolkata under the Economy and Growth programme. His primary interest is in international and development ...

Read More +