-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The Surya Ghar scheme will provide 10M households with solar rooftops by 2027, aiming for significant emissions reductions.

Surya Ghar Muft Bijli Yojana (solar home: free electricity programme) is a central government programme launched in February 2024 to provide solar roof top systems for over 10 million households by March 2027. This would give 300 kilowatt hour (kWh) of free electricity per month per household. The goal of the programme is to produce 1 terawatt-hour (TWh) of electricity, which is projected to reduce carbon emissions by 720 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2 eq) in 25 years (approximate life of installed solar panels).

While the logic behind the programme is simple and the goal laudable, implementation of the programme is likely to face a number of challenges. At a broad level, there may be problems in adoption of the programme as poor households, the primary target of the programme, get 100-300 kWh of free grid based electricity in many states and they may not value intermittent electricity that comes with long string of transaction costs attached. The effort required to access subsidies and install rooftop solar (RTS) systems may prove to be intimidating, even for affluent and more informed customers.

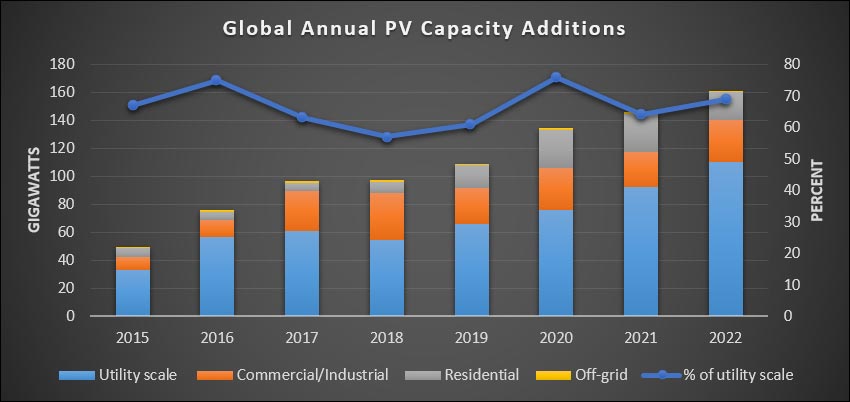

RTS accounts for over 40 percent of total global solar installations, against about 10-15 percent in India. India’s current installed capacity of RTS, approximately 12.8 gigawatt (GW) in 2023, is low compare to installations in other Asian countries. In China, RTS alone amounts to 254 GW of capacity, accounting for about 35 percent of total solar installed capacity. RTS capacity in China is almost half the total (fossil fuel and non-fossil fuel-based) power generation capacity in India. Although China has phased down national subsidies, local level incentives, cost competitiveness of solar PV systems, and concern over pollution continue to drive adoption of RTS systems. Wealthier countries in Asia like Taiwan have shown that RTS can be adopted widely even in high-rise buildings, which account for 63 percent of total solar installed capacity in that country.

Three months after the launch of the programme (May 2024), the Surya Ghar programme had 12 million registrations, over 800,000 applications and 56,000 installations. Effectively, only 0.4 percent of the registrations translated into installations. Though it is still too early to assign causes, it is likely that numerous small technical, economic, and procedural details between registration and installation are among many reasons for the drop in numbers. To begin with, there are far too many institutions involved in the decision-making and implementation chain. Among Central Ministries, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) sets policy guidelines, the Ministry of Power (MOP) sets applicable tariff structure, and the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change decides procedure on disposal of old solar panels. The Ministry of Finance is also indirectly involved in the release of subsidies. The delay in release of the central subsidy has already emerged as one of the issues is slowing down RTS installations.

Among Central Ministries, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) sets policy guidelines, the Ministry of Power (MOP) sets applicable tariff structure, and the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change decides procedure on disposal of old solar panels.

Potential customer has to approach REC India (formerly rural electrification corporation, a non-banking finance company), which is the national programme implementing agency, through its online portal for registration.Customer who will probably discover that the central financial assistance (CFA) covers only about 60 percent of the cost of the RTS system, has to approach designated banks for a loan at subsidised rates to fill in the gap in financing. Some states offer state financial assistance, which introduces yet another entity in the path towards RTS installation. The Surya Ghar programme is open to high-income customers, who are likely to become the largest beneficiaries rather than poor households who are the intended beneficiaries. As in the case of other subsidy programmes, affluent customers who have the capacity to navigate the complexities of the programme and invest in RTS equipment without opting for a loan could potentially appropriate most of the funding allocated for the programme. Banks may prefer larger and more affluent customers to lower risks. Although subsidies decrease as the capacity of the installation increases, the programme may not work in favour of poor households. High-end customers can voluntarily opt out of the subsidy component, but it is unlikely that they will as subsidy is one of the most attractive features of the programme. The Surya Ghar programme, in its current form, has no provision for ground-mounted solar systems. For households that do not have a house with a proper roof that can support RTS system, the option of ground mounted solar systems would have enabled access to the programme.

Then there is the state distribution company (Discom) that has to offer appropriate tariff and metering options to the customer. The Discoms, in turn, depend on the state electricity regulatory commission (SERC) for setting the tariff for the export and import of electricity for RTS customers. If the Discom uses net metering, the value of electricity the customer feeds into the grid is the same as the value of electricity the consumer imports from the grid. If it is net billing, the tariff of electricity exported to the grid is lower than the tariff charged for electricity used from the grid. If it employs gross metering, the electricity produced by the RTS is exported to the grid at a fixed rate (FiT or feed-in-tariff), and the consumer draws electricity at the tariff charged by the Discom. Gross metering would make the RTS programme more attractive for less affluent customers. Another issue is that SERC tariff revisions are made on an annual basis, which means the customer is not assured of his long-term revenue stream. This will discourage customers who take a long-term loan to procure the RTS system. Unless the agreed tariff is secured for at least as long as the period over which the consumer has to repay the loan taken for RTS installation, the customer may not see the option as materially beneficial. In Taiwan, where RTS accounts for over 60 percent of the installed capacity, the tariff is assured for as long as 20 years. Discoms are expected to mobilise capital to provide network access for loads up to 5 kilowatt (kW). This may not be received well by cash starved Discoms.

The Surya Ghar programme allows RTS installations in which the capital expenditure in the system is made by a third party other than the customer, under an arrangement with a renewable energy service company (RESCO). The RESCO will own the RTS system, and the roof-owner will be compensated by the RESCO in return for the use of the roof. Under the RESCO model for surya ghar, the third party is the central public sector undertaking (CPSU) that will have the responsibility to finance, install, own, operate, and maintain the RTS system. If this model becomes dominant, economies of scale will enable a substantial cost reduction for both the Government and the customer. The CPSU is expected to take on the 40 percent cost imposed on the customer, and this loan is expected to be repaid by the customer through export of electricity into the grid under a net metering arrangement over a period of 10 years. Past experience with the RESCO model suggests implementation is not likely to be as simple as it sounds.

Under the RESCO model for surya ghar, the third party is the central public sector undertaking (CPSU) that will have the responsibility to finance, install, own, operate, and maintain the RTS system.

Under the revamped distribution sector scheme (RDSS), the MOP has made installation of prepaid meters for all consumers except agricultural consumers, by March 2025. The compatibility between net meters and prepaid meters is unclear. The MOP has also directed SERCs to reduce time-of-day (TOD) solar tariff by at least 20 percent of regular tariff. This will reduce tariff for electricity export into the grid. In states without industrial load, high solar generation during the day may lead to dispatch problems. Discoms may have to design plans to shift peak loads to off-peak times using incentive offerings. There is also some confusion over applicability of cross-subsidy surcharge for RTS customers.

Then there is the vender who must have domestic manufacturing capacity for solar photovoltaic (PV) systems. Until domestic manufacture of solar panels takes off, availability of domestic panels will emerge as a factor slowing down installations. The price of solar panels, which depends on the price imported raw materials and components, may become a serious challenge affecting the progress of the programme. It is reported that domestic manufacturers have increased the price of panels after RTS programme was announced. With these price increases, it is likely that most of the funds allocated for the programme will be appropriated by domestic manufacturers, which may undermine the goals of the programme. This is particularly troubling given that domestic manufacturers also receive production linked incentives (PIL). Quality of available panels may also become a concern. Although solar panels may be guaranteed for about 25 years, system components, such as inverters may have a shorter life or guarantee period, which may reduce the viability of the programme. The availability of net meters and solar meters may also hold up installations, and so will the availability of skilled technicians to install and service solar systems. 30 GW of distributed generation connected to the grid without control and safety features of conventional generators may also carry fire and other risks that can seriously threaten grid stability. In South Korea, RTS systems of 1 megawatt (MW) and above are allowed to participate in wholesale power markets, which will require protocol and procedure to be followed. India has to first establish a wholesale market for power before offering the option of selling power to distributed electricity producers.

The success of the Surya Ghar programme depends critically on state governments that may or may not share the goals of the Central Government. The central government’s goals in the context of the programme include meeting multilateral carbon reduction commitments, increasing energy security, moving tariff subsidies to one-time capital subsidy, and promoting domestic manufacture. Some states may not value the Surya Ghar programme as a means to meet their renewable purchase obligation (RPO) because they have access to hydro power that can more than meet RPO targets at a lower cost. Some states may not see RTS as a means to access low-cost power, as they have access to dispatchable pit-head power at much lower tariff compared to what they have to pay RTS customers. The financial gains promised to the customer will come at the expense of Discom finances, which state governments may not favour. High residential electricity tariff (compared to industrial tariff) are one of the drivers behind the success of RTS in wealthier countries, but in India residential tariff is only about 80 percent of cost of supply of electricity and agricultural tariff about 25 percent of cost of supply compared to 150 percent of cost of supply for industrial and business sectors. High tariff is among key reasons why industrial and commercial consumers in India opt for RTS systems. If so, increase in conventional power tariff for households may be a may be a pre-requisite for mass adoption of RTS systems.

Source: International Energy Agency

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Akhilesh Sati is a Program Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

Vinod Kumar Tomar is a Assistant Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ms Powell has been with the ORF Centre for Resources Management for over eight years working on policy issues in Energy and Climate Change. Her ...

Read More +

Akhilesh Sati is a Programme Manager working under ORFs Energy Initiative for more than fifteen years. With Statistics as academic background his core area of ...

Read More +

Vinod Kumar, Assistant Manager, Energy and Climate Change Content Development of the Energy News Monitor Energy and Climate Change. Member of the Energy News Monitor production ...

Read More +