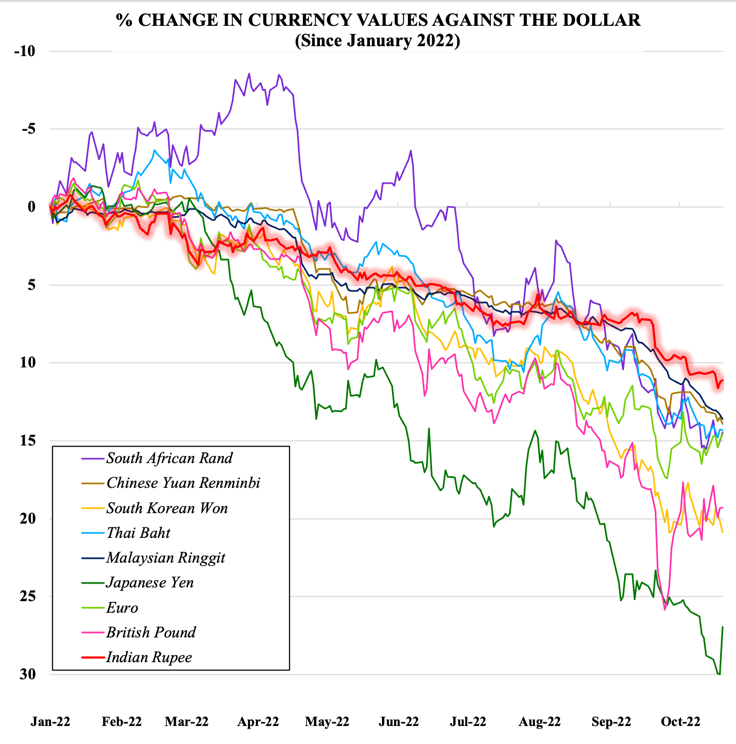

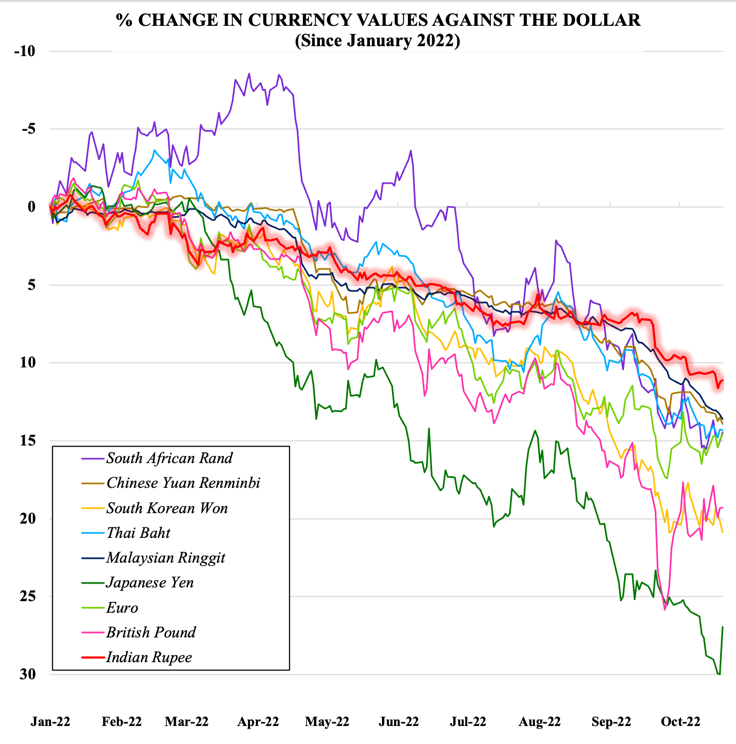

The Indian rupee has been quite the controversial newsmaker this year. Having fallen more than 11 percent against the US dollar so far in 2022, the rupee breached the much-feared 80-mark in July and went on to set record lows, touching

83 to a dollar late in October. With the United States (US) on a war path to curtail inflation and the supply side stifled by the conflict in Ukraine, even historically strong currencies like the euro and the British pound have plummeted against the raging dollar, more than the rupee.

Although India is far from a crisis given the safe cushion of forex reserves, it bodes well to be prudent, but without stifling growth.

Source: Database on Indian Economy, RBI

Source: Database on Indian Economy, RBI

While this fall has triggered much speculation and worry, the rupee’s depreciation should be assessed in a larger, more nuanced context. Even economic theory does not always peg a depreciating currency as a harbinger of doom. The article attempts to diagnose the extent of three macroeconomic phenomena in the Indian economy to better assess the impact of a falling rupee–focusing primarily on the trends in trade, the behaviour of foreign investment, and the response of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

A (trade) balancing act

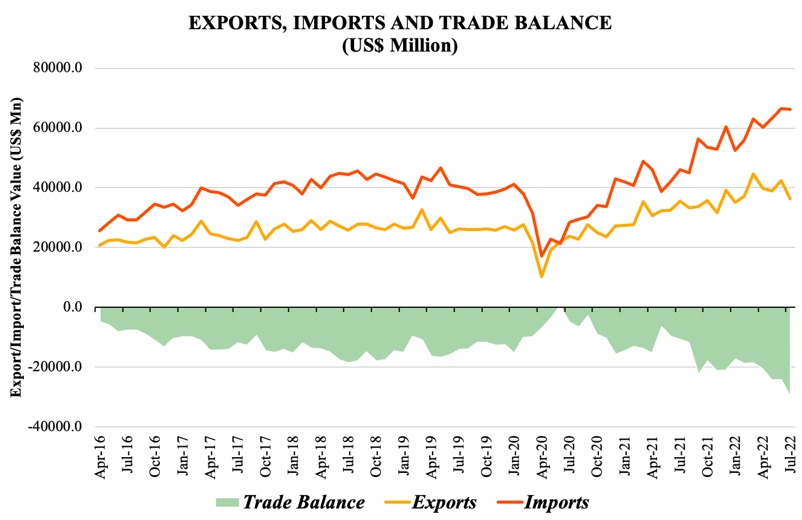

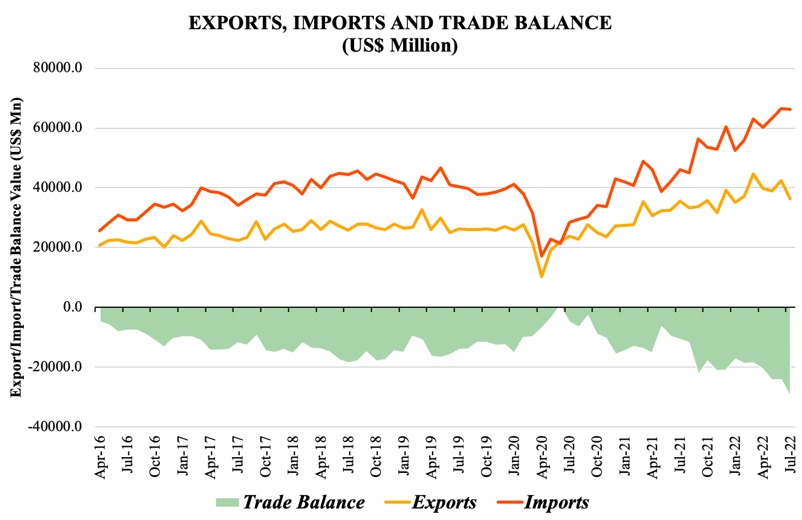

The first phenomenon is one of the biggest worries caused by a falling rupee–a rise in import costs, threatening higher inflation and a widening trade deficit. However, there also exists a ray of hope–a depreciated currency implies cheaper, more competitive exports and therefore, a possible export-led boost to the domestic economy. The net effect of these opposing forces would determine the impact of a depreciating currency on an economy.

Source: Database on Indian Economy, RBI

Source: Database on Indian Economy, RBI

A brief glance at the statistics points to a widening trade deficit, with the rise in imports far outstripping the rise in exports and the first quarter of FY 2022-23 seeing the highest current account deficit (CAD) in nearly a decade. However, there is room for optimism. The import bill has risen not only on the back of a raging dollar and hardening crude prices but has also been spurred by strengthening domestic demand and manufacturing–as evidenced by a

robust Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI) of 55.3 in October. Unfortunately, there is a reason that warrants for some worry on the export side. Although service exports have done fairly well in FY 2022-23,

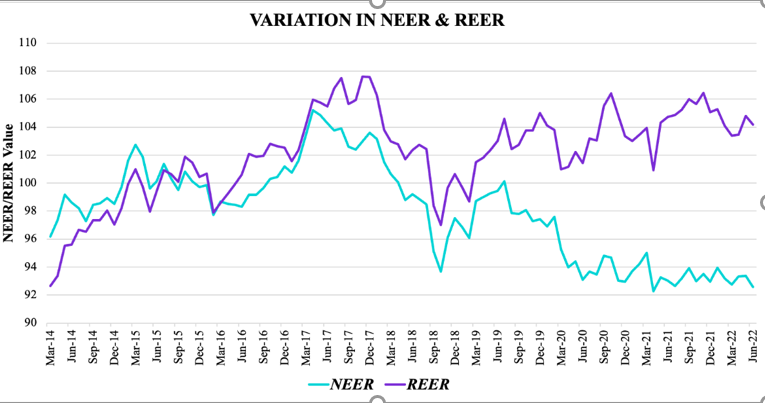

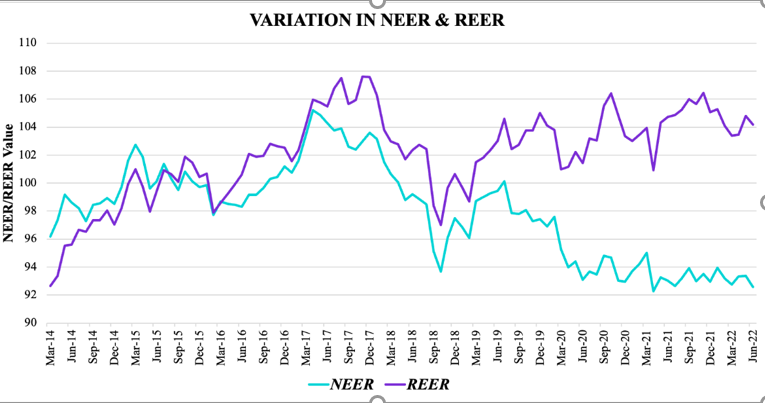

merchandise exports have remained subdued and could soon worsen due to economic downturns in Europe and the US. Even indicators of international competitiveness such as the NEER and REER show limits to the export-led benefits of a depreciated rupee. The nominal effective exchange rate (NEER) is a trade-weighted currency index–a rise in the NEER indicates an appreciation of the local currency against a weighted basket of currencies of its major trading partners. The real effective exchange rate (REER) is the NEER adjusted for inflation–the NEER is adjusted by the ratio of domestic prices to foreign prices to give the REER.

Source: Database on Indian Economy, RBI

Source: Database on Indian Economy, RBI

In recent years, India has seen a growing divergence in the values of the NEER and REER – particularly due to

higher prices in India as compared to its export partners. While the NEER has been falling, pointing to a nominal depreciation in the value of the rupee, the REER has risen, indicating an appreciating rupee in real terms. India’s woes lie wholly in this growing gap. The value of the currency is falling in nominal terms, making imports more expensive–but rising in real terms, essentially wiping out the possible benefits of cheaper exports. The rising REER also points to an overvalued rupee–indicating the possibility of further depreciation so as to fall in line with macroeconomic fundamentals. Therefore, while there is comfort to be found in the link between rising imports and a strong domestic economy, gains from the export side remain elusive.

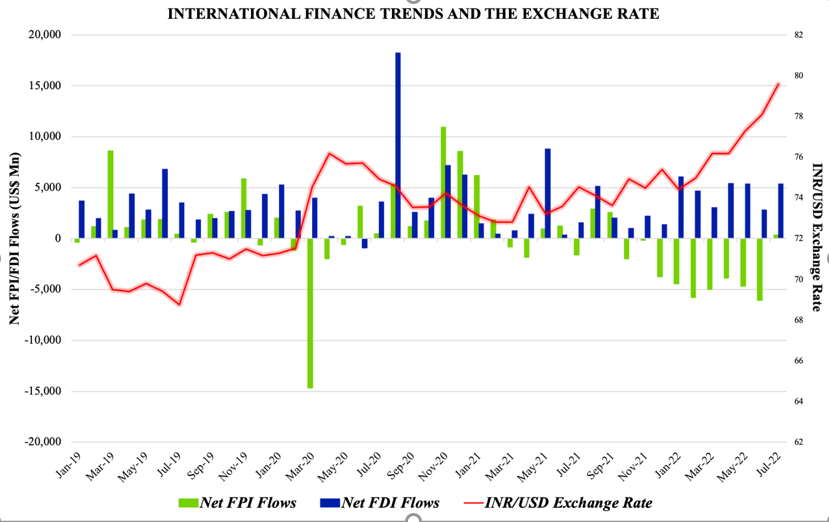

Capricious capital

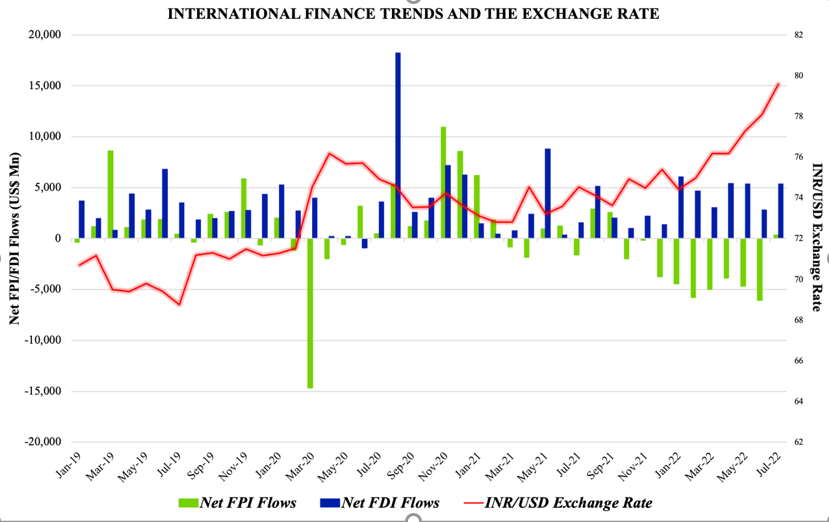

The rupee has a complicated relationship with the moody foreign portfolio investors (FPIs). A weaker rupee can discourage FPIs. In turn, FPI outflows can further push the rupee to depreciate. With the exception of July and August–each month in 2022, FPIs turned net-sellers of Indian assets in the debt and equity markets, with the calendar year seeing a total of $23.2 billion in FPI outflows by the end of October.

Source: Database on Indian Economy, RBI

Source: Database on Indian Economy, RBI

With the rupee losing value against the dollar, and interest rates around the world rising, NRI deposit flows also fell in the five-month period from April to August 2022, down to US

$1.4 billion from US$2.4 billion a year ago. Moreover, given the prevailing geopolitical uncertainty and rising interest rates around the world, the interest differential between emerging (‘risky’) economies such as India and developed (‘risk-free’) economies is narrowing, giving investors little incentive to invest in ‘riskier’ economies in the absence of higher returns. These outflows can be hazardous–as foreign money moves out of India, rupee-denominated assets are sold, increasing the pressure on the rupee to depreciate. And if investors see the possibility of further depreciation in the future, it is possible that they dump assets even faster, leading to a sharp fall of the rupee. Nonetheless, FPIs are often short-term investment flows, subject to the mood of the international market and highly dependent on global factors.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) instead, is a better judge of investor confidence in the long-term growth prospects of an economy—constituting more illiquid investments in infrastructure and productive assets. Net FDI flows have remained positive and are set to grow, with

April-June 2022 seeing an inflow of US$13.6 billion, higher than the same period last year. Even Indian stock markets have remained resilient, particularly on the back of large net-purchases by domestic institutional and retail investors, offsetting the equity sell-off by foreign investors. However, net foreign investment (FII) flows did turn negative for a few months in 2022, and while rebounding FPI and resilient FDI do point to a more optimistic opinion of India among foreign investors, foreign investment is absolutely crucial at this juncture in India’s growth story and must be watched closely.

RBI to the rescue?

Over-tightening of monetary policy and excessive intervention in the currency market can pose significant risks to the country’s growth prospects

All eyes are now on the RBI and it certainly has a lot on its plate. Inflation can be stubborn, capital remains whimsical, and the currency is depreciating. In an effort to defend the rupee, the RBI has intervened and sold off some of its foreign exchange reserves. The reserves stood at US

$524.52 billion as of 21 October 2022, witnessing a fall of over US

$115 billion since the beginning of the year. FII outflows have undoubtedly contributed to this fall and the widening CAD is further threatening to stretch the reserves to their seams. The RBI has, however, repeatedly stated that

most external indicators such as external debt to GDP ratio, net international investment position to GDP ratio and the ratio of short-term debt to reserves reflect India’s relatively comfortable position in meeting its external financing requirements–even in contrast to other emerging economies. However, one must not forget that the primary task of the RBI is to ensure price stability. Given the overvalued REER, the possibility of further rate hikes by the Fed and the prevailing geopolitical uncertainty, it is very likely that the rupee will depreciate further, albeit at a slow pace. Over-tightening of monetary policy and excessive intervention in the currency market can pose significant risks to the country’s growth prospects and the RBI must be careful to intervene just enough to quell volatility, without expending an inordinate amount of reserves.

The Indian advantage

Both the RBI and the government need to, therefore, play a tricky balancing act. The current account deficit needs to be monitored–while a rise in imports could stem from robust domestic demand, if allowed to balloon unchecked, it could erode investor confidence and exert pressure on the rupee. This widening CAD, together with a muted capital account, presents (a very real) threat of a BoP deficit–resulting in further depreciation and drawdown of reserves. Although India is far from a crisis given the safe cushion of forex reserves, it bodes well to be prudent, but without stifling growth. At the same time, India has the unique opportunity to be an outlier in a slowing global economy – with relatively robust macroeconomic fundamentals and a currency far from a free-fall. Particularly, India has the chance to leverage its relatively healthy growth rates and rising infrastructure and capital expenditure to attract foreign investment—spurring growth and strengthening the capital account. Investor confidence has been steady, with the country seeing a record high of

annual FDI inflows of US$84.8 billion in FY2021-22 in spite of the pandemic and volatile geopolitical scenario. This confidence needs to be leveraged and by positioning India on the international stage as a thriving and stable haven for investments, both the country’s growth and forex needs can be met. Therefore, although the falling rupee has caused worry for a few economic indicators, with sufficient policy support, the domestic economy could emerge as an outlier in a global downturn.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The Indian rupee has been quite the controversial newsmaker this year. Having fallen more than 11 percent against the US dollar so far in 2022, the rupee breached the much-feared 80-mark in July and went on to set record lows, touching

The Indian rupee has been quite the controversial newsmaker this year. Having fallen more than 11 percent against the US dollar so far in 2022, the rupee breached the much-feared 80-mark in July and went on to set record lows, touching

PREV

PREV