In today’s interconnected world, cyberspace is critical to almost every domain, from healthcare and commerce to finance and security.

Cyberspace is a global domain available to anyone with access to a computer and an internet connection. With few entry barriers and high anonymity, it is the perfect ground for nation-states and non-state actors to conduct acts of hostility, aggression, and warfare with little to no consequences, making cyberspace an arena for pursuing geopolitical and geoeconomic rivalries. For instance, the ongoing Russia-

Ukraine conflict has a significant cyber warfare component.

Nation-states are striving to dominate cyberspace. However, creating a national cyber force is a time-consuming and costly affair. Not all nation-states have the necessary time or resources. Therefore, many are turning towards non-state actors to bridge their shortcomings. This article examines how state actors use non-state actors in cyberspace. It analyses the driving factors behind their use and their international political implications and consequences.

Motives behind the use of non-state actors

A

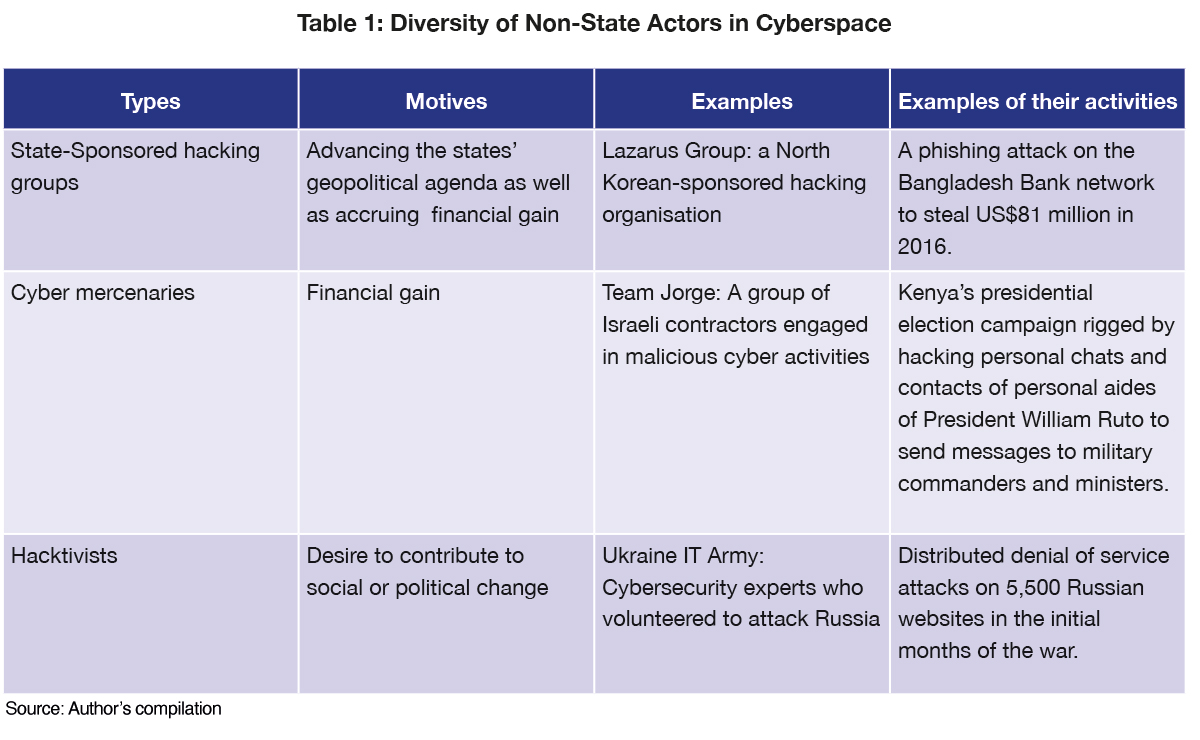

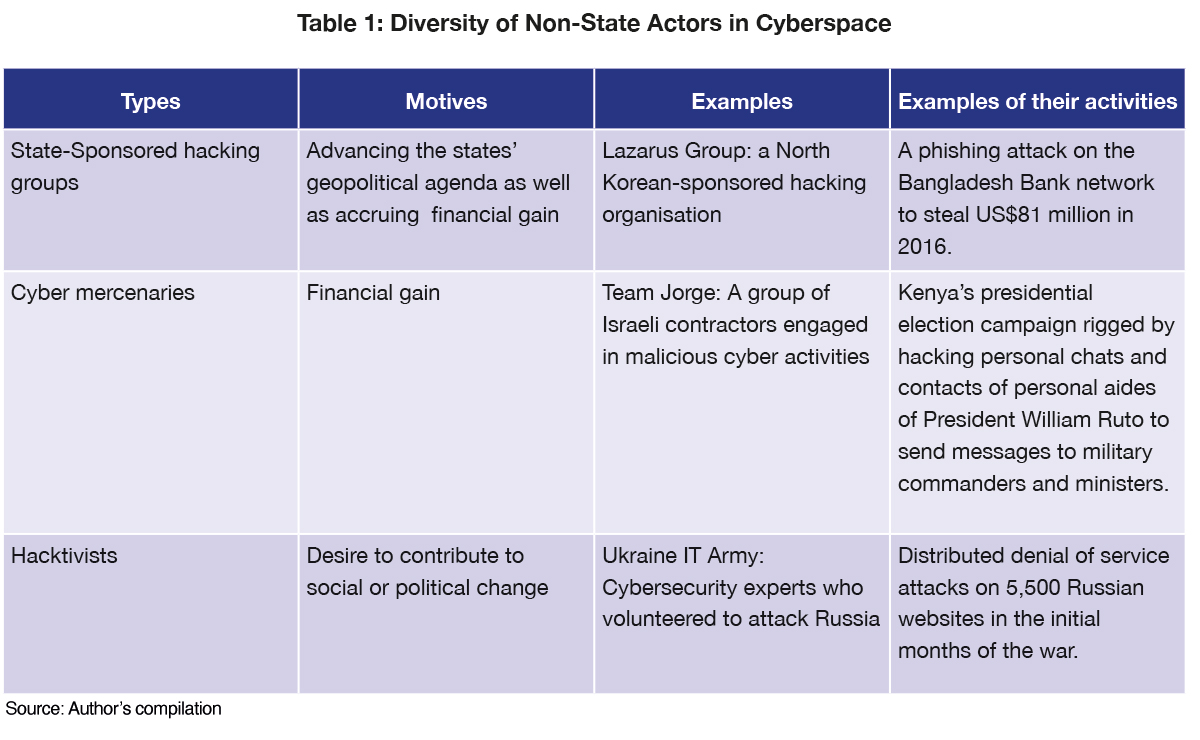

cyber non-state actor is an entity with no specific physical territory or territorial sovereignty that operates in cyberspace. It can include individuals, groups, or organisations that operate independently or in association. Non-state actors can significantly threaten governments, businesses, and individuals.

With few entry barriers and high anonymity, it is the perfect ground for nation-states and non-state actors to conduct acts of hostility, aggression, and warfare with little to no consequences, making cyberspace an arena for pursuing geopolitical and geoeconomic rivalries.

The principal reason states contract non-state actors is to protect themselves. Cyberspace already ensures a high level of anonymity, making

attribution difficult. Non-state actors provide additional protection to the states during cyberattacks, as they can claim plausible deniability and avoid blame to evade indictment. Thus, using contractors to carry out hacking or cyber warfare against other countries allows states to

avoid the application of international law while reaping the benefits of these actions. States are inclined to use non-state actors when the proposed actions are clandestine or illegal. For instance, North Korea uses

Bureau 121, a hacking group, to carry out cyberattacks primarily against South Korea while maintaining a certain distance from their repercussions.

The following table illustrates the various types of non-state actors utilised by states for launching cyberattacks.

In addition, using non-state actors is highly beneficial for states, as the national hacking talent pool is minimal. Training individuals for high-level hacking is time- and capital-intensive.

Contracting non-state actors allows states like Iran to benefit from their manpower and knowledge, bridging their capacity gaps with no startup cost. The Iranian government reportedly hires cyber mercenary groups such as

MuddyWater to access expertise and resources by targeting government and commercial websites globally.

These non-state actors conduct specialists-designed rapid attacks and redefine power dynamics between states. In traditional warfare, the country with a superior military, more financial resources, or better technology has a greater advantage than countries that lag on these three counts. However, cyberspace and non-state actors have reduced that gap. Governments no longer need their own cyber force since they can rely on

non-state actors to carry out their operations. For example, during its war with

Russia in 2008, Georgia, though lacking the cyber manpower to confront Russia, relied on groups of private American hackers to fight back against Russian cyberattacks, showing how smaller countries can hire cyber mercenaries of equal calibre as those of more powerful nations and level the playing field.

The Iranian government reportedly hires cyber mercenary groups such as MuddyWater to access expertise and resources by targeting government and commercial websites globally.

The use of non-state actors is not always confined to acts of aggression. States also contract these organisations to strengthen their cybersecurity capabilities and infrastructures. Protecting national interests by securing cyberspace is vital. Every crime that can happen in cyberspace can also happen in real life. However, they are more dangerous due to three factors:

- The cyber warfare factor—weapons are more easily created

- The remote factor—distance doesn't matter

- The safety factor—physically and psychologically removed

Non-state actors can enhance a state’s security. For instance, the

“IT Army”, a group of volunteer cybersecurity experts created by Ukraine’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Albertovych Fedorov, helped strengthen the cyber defence of Ukraine’s critical infrastructure.

One of the main non-state actors countries use is

state-sponsored groups. They have a direct link to the state apparatus and advance its political, military, and commercial goals. Often state-funded, they do not necessarily have a monetary motive, making them more dangerous than independent hackers. They can be used for espionage, propaganda, disruption, sabotage, and retaliation against adversaries. Even though these attacks are hard to attribute, their targeting pattern can indicate the likely perpetrator. State-sponsored attacks, if detected, can be considered acts of war and lead to serious diplomatic confrontations. In February 2021,

APT42, an Iranian-sponsored cyber espionage group, targeted the email credentials of a senior Israeli government official by mimicking the Gmail login page. These types of attacks further strained the relations between the two countries.

Cyber mercenaries pose a bigger danger, as the states have no direct control over these mercenaries, and the mercenaries have no deep-seated loyalty to the state contractor.

Meanwhile, a new type of non-state actor has quietly emerged in cyberspace in the form of

cyber mercenaries. Just like regular mercenaries, they aim to complete the mission given by the client who has contracted them in exchange for a monetary reward. However, their field of operation is in cyberspace. They are hired for specific operations and do not necessarily have political or ideological linkages with their clients. Cyber mercenaries have changed how attacks are carried out by providing quick manpower to deficit states or groups. Cyber mercenaries pose a bigger danger, as the states have no direct control over these mercenaries, and the mercenaries have no deep-seated loyalty to the state contractor.

Balancing non-state actors and cyberspace management

What are the implications of non-state actors in cyberspace? Their operations should not be underestimated or overlooked due to their disruptive and destabilising nature. They strengthen states by making them a bigger threat to their enemies, particularly in the absence of a legal framework. For instance, the cyber mercenary group

Team Jorge claims to have interfered in 27 presidential-level campaigns worldwide through hacking, disinformation campaigns, and planting fake intelligence. Such types of groups imperil the functioning of democracies.

As these non-state actors don’t operate within the bounds of the law,

legislation is necessary to curtail their activities. Some states have started responding to these attacks by enacting legal measures. Currently,

80 percent of countries around the world have enacted cybercrime legislation to end malicious cyber activities; for example, the European Union’s

Network and Information Security Directive.

Yet, it is also true that many of these countries have utilised non-state actors. States have little to no incentive not to use them, as the drawbacks are few. And as geopolitical rivalries deepen with time, this use of non-state actors is only set to grow.

Aishwarya Raman is an intern at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

In today’s interconnected world, cyberspace is critical to almost every domain, from healthcare and commerce to finance and security.

In today’s interconnected world, cyberspace is critical to almost every domain, from healthcare and commerce to finance and security.

PREV

PREV