-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Against several odds, what began as the Srinagar conversation has transformed into the Srinagar Consensus, making it arguably the most far-reaching policymaking process in independent India.

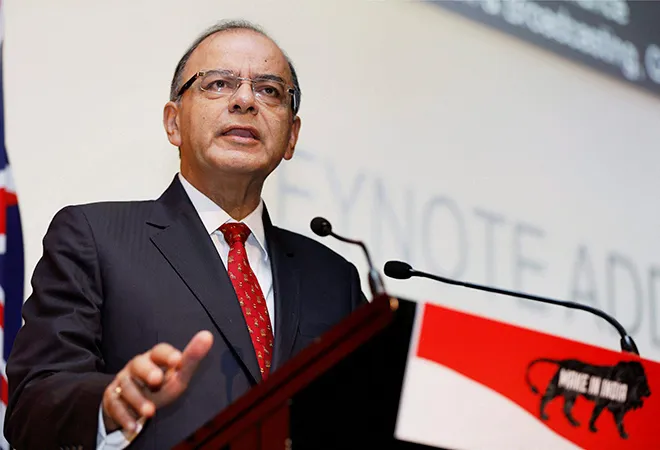

Image Source: File Photo

The first-ever joint fiscal policy of Central and State governments, articulated in the Srinagar Consensus on Friday (19 May), is the biggest gamble on economic growth that India has taken so far. It embraces two pillars on which the economic stability of any government stands. The first pillar is inflation control. "There is hardly anything where rates have been hiked," Finance Minister Arun Jaitley said after the Goods and Services Tax (GST) Council meeting in Srinagar. "Either the present rates were maintained or they've been brought down." Which means, in the aggregate, the GST will not increase prices in the economy, which is good politics through happy households, supported by good economics that keeps the fiscal books intact.

The second pillar stands next to inflation and by implication suggests that Mr. Jaitley, along with other 32 state and union territory finance ministers, is presuming that growth from GST implementation will offset the transition into an entirely new and high-compliance tax system. The question they are addressing is: how can we keep voter-consumers satisfied with low incidence of inflation through low GST rates and yet increase the net tax inflows? The answer is simple: by taking a bet on, and expecting an increase in, value addition by producers of goods and deliverers of services, on which the GST will be charged, to make good any shortfall in tax revenues due to low or flat rates. In the language of business, going for scale rather than margins. Which means, the Council is presuming the Indian entrepreneur, and through her the Indian economy, is going to flourish because of the efficiencies the GST brings. Any downside here would pinch the fiscal deficits of both the Centre and State governments.

Read also | The process of GST must not become larger than its purpose

Against several odds, what began as the Srinagar conversation has transformed into the Srinagar Consensus, making it arguably the most far-reaching policymaking process in independent India, a permanent and positive change on the federal polity map, and a landmark in the way economic reforms are envisioned. What makes it a 'consensus' is the manner in which governments have come together to forge together an economic policy that is transformative in essence, all-encompassing in scope, and carries the conviction of participative democracy not only among states but between the Centre and States as well.

In contrast, recall the 1991 reforms, all of which were led and dominated by the Centre — from the devaluation of the Rupee to the removal of Licence Raj and the creation of financial regulatory frameworks to the relaxation of barriers to foreign capital. Or remember the way State governments had to pay obeisance to the Planning Commission for funds until it was replaced by Niti Ayog. The GST Council has changed all that — it comprises the Union finance minister, the Union minister of state for finance, and finance ministers (or any other nominated minister) of every State. Together, the council takes decisions on taxes and exemptions, laws and principles, rates and provisions.

"GST Council is India's first federal institution, both fiscally and politically," Jammu and Kashmir Minister of Finance Haseeb Drabu said. "The GST will bring major changes in fiscal and political side of India's federal structure because of which coercive federalism will pave way for cooperative and competitive federalism." The Assam Finance Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma said the Council's 14 deliberations over two days brought trust between State finance ministers. The nature of the institution is such that it has forced ministers of states and the Centre to empathise with one another and collaborate in a way that delivers optimal results — the transformation of India into a single market.

But the politics of GST was a success foretold. Bringing political parties of various ideologies, families, constraints and visions on a single legislative table is no mean feat — the baton of the bill went through several governments before it became law. It was the economics that needed to be thrashed out, taking the diverse needs and strengths of various geographies into account. And if on the same rates or lower, the inflation rate and fiscal finances remain in shape, as Mr. Jaitley said — a theory that will turn into evidence only after the first two quarters of GST implementation are behind us — it spells a never-seen-before successful harmony of India's federal political economy.

Technically, the final rate around which the Council's decisions can be evaluated has not been declared — only the incomplete rate schedule for goods and the compensation cess rates for different supplies have been released. This rate, defined as the 'revenue neutral rate' (RNR), or the single rate that preserves revenues of the Centre and the States at desired levels, arrived at by capturing all the rates and the revenues accompanying them, remains elusive for now. The 2015 Arvind Subramanian Committee had placed the rate within a range of 15.0 to 15.5%, while five years earlier, the 2009 Arbind Modi Task Force on Goods and Services Tax had called it out at 11%, exclusive of revenue gains from increased compliance and GDP growth.

Presuming the GST Council has gone with Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian's 15.0 to 15.5% recommendation — a number that some of his colleagues disagree with — and the rates remain either the same or lower, there is a new faith in the entrepreneur that the Council is placing. It has either relegated the expected problems of compliance behind its hyper-optimistic political stance, or has been blinded by its political success, or is simply unaware of what is happening to the rulebook under its nose. It is presuming that the transition to GST will be smooth and friction-free, that businesses will be ready to shift to GST from 1 July when the new regime comes into force, that the GST Suvidha Providers will provide the needed knowledge lubricant, that entrepreneurs will march to the GST tune in time.

Perhaps they are right. They have to be — else, the fiscal books will not balance. And enough warnings have been given. "The gross fiscal deficit (GFD) to gross state domestic product (GSDP) ratio in 2015-16 breached the 3% ceiling of fiscal prudence for the first time since 2004-05," the RBI report on State Finances noted last week. "Information on 25 states indicate that the improvement in fiscal metrics budgeted by states for 2016-17 may not materialise." Among the major violators here are Jammu and Kashmir whose 2016-17 GFD as a percentage of gross state domestic product stood at 8.8%, followed by Goa at 6.8%, Rajasthan at 5.6%, Haryana at 4.6% and Uttar Pradesh at 3.9%. All five are States where BJP is either governing or is a governance partner. And with its ₹36,000 crore farm loan waiver, Uttar Pradesh is all set to double its deficit.

Read also | Are loan waivers breeding a defaulter nation?

There is no way that the Srinagar Consensus would take such a fiscal risk and certainly not in the first year of its implementation. There are some gaps in the final numbers that prevent a definitive analysis — the rates on gold, for instance. The Council is probably betting on economic benefits from the ease that a uniform rate structure across the country brings to doing business. It may also be gambling on the end of cascading taxes, a financial and administrative menace. It could be making a wager that reduced transaction costs will make India's exports more competitive. All of which come embedded into the GST. But it may be overestimating the transition time and compliance cost to entrepreneurs that look good on paper and in rulebooks but may spring a shock while implementing.

Fiscal gambles are not new to India. In 1991, then Finance Minister Manmohan Singh took a gamble to reform — it worked. From 93.5% peak income tax rate in the early 1970s under Finance Minister Y.B. Chavan to 50% under Finance Minister V.P. Singh in 1985-96 to 30% under Finance Minister P. Chidambaram in 1997-98, the tax rates have been steadily coming down — they have worked too. At the time of announcement, all these reforms felt outlandish, difficult, even impossible. But finally, all of them increased the tax base, expanded markets, created wealth. The Srinagar Consensus seems to be following the same trajectory.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Gautam Chikermane is Vice President at Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. His areas of research are grand strategy, economics, and foreign policy. He speaks to ...

Read More +