Causing an apparent surprise,

news broke last week that hydropower exploitation in the downstream of the Yarlung Zangbo had been made a part of the proposals for China’s 14

th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025). It is quite rare that a seemingly inaccessible and largely obscure stretch of the Himalayas should suddenly be in the spotlight of global news because of proposed human construction with no parallels on the planet. The project envisages a ‘historic’ dam on the Yarlung Zangbo river — the longest and most important tributary of the Brahmaputra contributing 38 percent (measured at Pasighat) to the total flow at Guwahati.

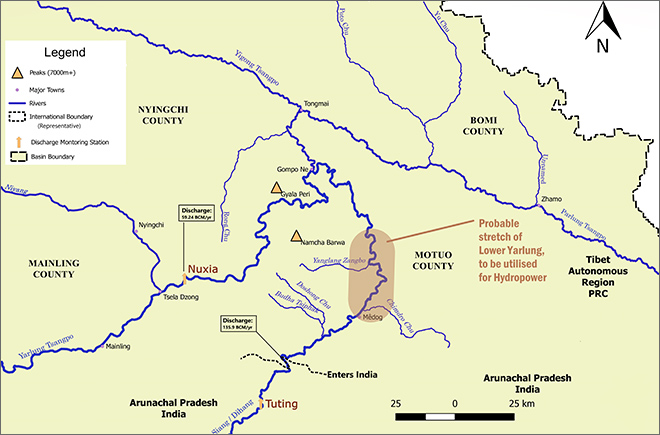

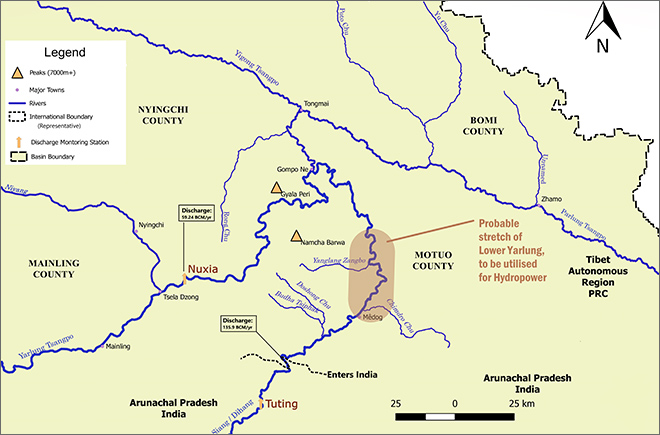

This massive 60GW project is planned to be undertaken at the Yarlung Zangbo Grand Canyon (YZGC) — a spectacular geological formation where the river takes a ‘great bend.’ The Yarlung plunges from the staggering heights of the Tibetan Plateau by tracing active fault lines and enters Arunachal Pradesh as the Siang or Dihang river. A specific 50-kilometre section of the bend will be utilised by making the water drop 2,000 metres, thereby, generating hydropower which is supposedly three times stronger than that of the Three Gorges Dam.

Untangling geopolitics

This move was quickly contextualised as China waging a ‘water war’ with India by connecting the hydropower proposal to the military standoff in the Himalayas and the occasional skirmishes throughout the summer along with China’s increasing maritime presence in the Indian Ocean. A fact that is largely ignored in this quick and make-believe juxtaposition is that technical prowess was not achieved in one single instance.

A particular inventory map for Hydropower projects prepared by Hydrochina had identified a series of dams at the ‘great bend’ almost two decades back. China had been perfecting the technique to harness the energy of flows for a long time now and the Three Gorges Dam and Baihetan Hydropower Station are stellar examples of its technical prowess.

Therefore, it was more likely than not that the country’s attention would ultimately rest on this immensely lucrative site.

According to data, the Yarlung is the least exploited for hydropower of all major Chinese rivers with only 0.3% development level achieved so far, while the figures for Yangtze, Yellow and Pearl are 24.6%, 34.2% and 58% respectively. The site near Medog is the final frontier that will test the best of China’s technological advancement to tame arguably the wildest stretch of any river on Earth. This was also made possible by the fact that

the nearest town to the supposed construction site — Medog of Motuo County in Nyingchi Prefecture — had recently been connected to the rest of the country, thereby, making it the last roadless county to be opened to traffic. Long story short, this Medog project was expected and its announcement is synchronised with the Chinese Communist Party’s fifth plenum. India should not make the mistake of bundling it with the other hostilities and assume it to be another flashpoint in Indo-China relations.

Figure 1: Probable location of the lower Yarlung Dam based on an existing map by Hydrochina; Discharge data for Nuxia from Cuo et al. (2019) and for ‘point leaving China’ from Cuo et al. (2014).

Figure 1: Probable location of the lower Yarlung Dam based on an existing map by Hydrochina; Discharge data for Nuxia from Cuo et al. (2019) and for ‘point leaving China’ from Cuo et al. (2014).

Altered flow regime

India certainly has some legitimate concerns if a dam were to be constructed. But,

contrary to the hue and cry, these do not pertain to loss of water and water insecurity for the whole of Northeast India. Owing to the supposed site of construction — at the great bend and near the town of Medog — this project will tap into the monsoon-dominated precipitation regime unlike previous projects on the mid-stretch of the Yarlung. Consequently, it could significantly alter the flow regime in the downstream if the dam were to operate keeping in view

hydropeaking — the discontinuous release of turbined water due to peaks of energy demand.

It may cause extreme flow variability over a diurnal cycle even if it is only a run-of-the-river scheme, particularly during the lean season. The glacier and snowmelt along with groundwater contribution through springs and baseflow feeding the river may not be sufficient to run the plant at installed capacity and cater to hydropeaking. Therefore, the water will have to be stored in a reservoir and only the environmental flow might get released. As a result, the Yarlung/Siang will have relatively less water during a few hours of the day representing the minimum flow conditions of the year, while for the rest of the day, it could represent the monsoonal flow of a uniform nature for as long as the units/turbines generate hydropower.

Ecological disruptions

The obstruction will not just disrupt the longitudinal connectivity of the river but is also bound to have a detrimental impact on the constituents and productivity of the riverine ecosystem in the downstream over a long period. A retaliatory 10 GW dam on the Indian side to supposedly ‘offset’ this impact of the Chinese, as being

claimed by the government, will not help as it is also likely to cater to hydropeaking. The cumulative impact of these two megaprojects might aggravate ecological degradation, converting lotic ecosystems into lentic ones. Rather than ‘offsetting’ the impact, I sense that India is planning to expedite the project on the Siang to claim

prior appropriation on the waters of the Yarlung before China completes its own project in the upstream.

A large volume of suspended sediments also gets generated due to the very high anomalous rainfall in this stretch. According to

estimates, the Siang generates 7,694 Ha.m. of average annual suspended sediment load (measured near Pasighat), which is 32% of the total within the Brahmaputra valley (middle reach). A significant amount of the Yarlung/Siang’s sediments may get trapped behind the walls of the dams by China and India unless major technological innovation is put to use. Moreover, the release of clear water will increase erosion in the downstream — of riverbank and riverbed, as has

also been observed in the case of the Three Gorges Dam. The extent to which this impact will cascade downstream will depend upon the specificities of the projects and their exact locations. The region downstream of Pasighat is already prone to erosion for reasons related to

neotectonics. The river also creates depositional features in this stretch and supports rich biodiversity. The long-term consequences of an altered flow regime, increased erosion and reduced sediment supply can be far-reaching simply because of the large proportion of water and sediments contributed by the Siang.

The landmine of natural hazards

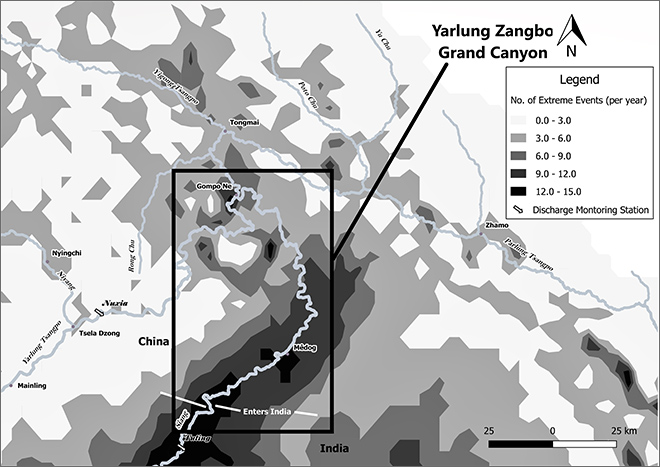

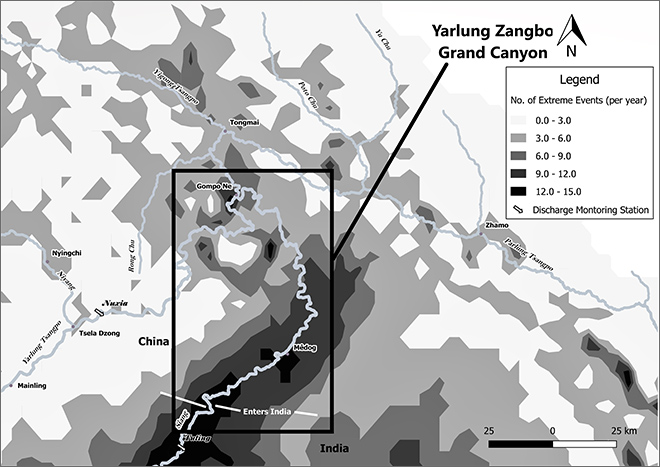

Figure 2: Map showing Extreme Rainfall Events at the ‘Great Bend’ | Source: Ghosh et al 2019

Figure 2: Map showing Extreme Rainfall Events at the ‘Great Bend’ | Source: Ghosh et al 2019A major concern regarding dam construction at the ‘Great Bend’ is also the risk of dam burst in the face of emergencies created due to the prevalence of natural hazards. The zone is

seismologically active, and the endogenic forces result in frequent earthquakes of varying magnitude. Moreover, due to a streamlined influx of moisture through this corridor and anomalous precipitation, the effect of exogenic forces is also significantly high. These result in frequent occurrences of avalanche, landslide, and cause debris to flow downhill. The two countries have coordinated in the past for creating emergency response

arrangements at the instance of landslide-induced damming of waters in the region downstream of Nuxia and upstream of Tuting, including the catchments of Yigong Tsangpo and Parlung Tsangpo.

In the same manner, India needs to be taken into confidence right from the very initiation of the project to foster trust and collaboration. A token ‘

good communication,’ as claimed by the Chinese embassy might not be enough. India should continue to voice its legitimate concerns through the already established channel — the Expert-level Mechanism (ELM) on transborder rivers. India has concerns regarding the location, design, and other technical details about the dam(s) in the lower Yarlung stretch. China needs to disclose the protocols that it plans to develop for exigencies that may arise due to the risks associated. Even a single act of allowing a large quantity of water to be released due to an extreme rainfall event, the chances of which are quite high in the YZGB (Ref. to Fig 2), might cause devastation in the downstream. This is not to mention that India will have to match the operations of the Siang Dam with that of the Lower Yarlung Dam and that would invariably necessitate the two countries to cooperate.

However, despite everything said and done, the ecological impact of such massive constructions might be irreversible and such concerns will have to be considered by both countries cumulatively before proceeding with any plans. The river, along with its riverine and riparian ecosystems, is a single entity and only a cumulative impact assessment will suffice.

Lastly, this analysis is based on whatever scarce data that already exists in the public domain and suffers greatly from the lack of it! Hence, this analysis should largely be treated as indicative. Due to security reason, both countries maintain strong control over the dissemination of hydrological data which has time and again proven to be the sole stumbling block for objective and accurate analysis of issues such as this. Declassification of data and making it available for everyone along with the full disclosure of all project details will be the first step towards confidence-building in a largely charged and vitiated climate of foreign relation between the two Himalayan neighbours.

Following Bookhagen (2010), an extreme event is defined as the daily rainfall magnitude whose probability of occurrence exceeds the 90th percentile, with percentiles being identified from the probability density function of the 3-hour rainfall data collected over a 11-year period (1998 – 2009).

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Causing an apparent surprise,

Causing an apparent surprise,  Figure 1: Probable location of the lower Yarlung Dam based on an

Figure 1: Probable location of the lower Yarlung Dam based on an  Figure 2: Map showing Extreme Rainfall Events

Figure 2: Map showing Extreme Rainfall Events PREV

PREV