-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

India may well find itself being dragged into a confrontation that is not of its own making, especially if the Chinese perceive our closeness to the Americans as supportive of their attempts to restrain them.

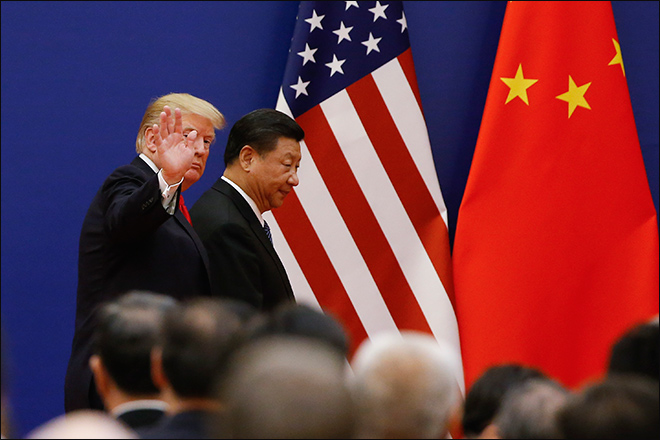

Image Source: Getty Images

While climate change may be rapidly warming up of our oceans, it cannot be compared to the pace at which the “Indo-Pacific” is heating up after Prime Minister Modi and President Trump recently danced the tango at Houston for the world to see. In fact, we also have Prime Minister Abe of Japan and Prime Minister Morrison of Australia waiting in the wings to accompany him in a quick foxtrot and complete the “Quad”. Obviously, the Americans have reason to worry as China powers its way up the food chain and threatens their economic and technical prowess with the likes of Huawei and its 5G technology leap. Add to this President Xi’s combative foreign policy and we have a potent brew of economic and military muscle-flexing that leaves friends and neighbours in Asia apprehensive and wary of its intentions.

India, given its size and geo-strategic location, finds itself being wooed by the United States and its allies since it is seen to have the potential to become a suitable countervailing force to China’s hegemonic ambitions. Moreover, given China’s symbiotic relationship with Pakistan, to befriend the only super power and its allies makes eminent sense for India. And appears to be the best way forwarded in the coming decades. Thus, to be feted in the manner that he has, this must make Mr. Modi believe that his outreach is paying rapid dividends. Yet, success in such matters can be a fickle friend, more so if one has friends like President Trump, as the Kurds are discovering to their cost. In the prevailing circumstances one would do well to heed that old Latin proverb “festina lente”, or “Make haste slowly.” Indeed, it may be worthwhile to pause and reflect on how closer ties with the America would help, especially given that through the Cold War India’s adeptness at straddling two canoes worked well for it, barring an odd exception or two.

Why does the West really feel threatened by China’s rise? Unmistakably, it is not only hugely uncomfortable with China’s unbridled ambition to be top dog, but also with its obvious contempt for democratic norms and its unwillingness to play by the existing rules. However, we would do well to remind ourselves of the observations made by the late English economic historian, Angus Maddison. He showed us that as late as the early 18th Century, China’s share of World GDP was around 26% until imperial depredations by the West reduced it to virtual penury. Moreover, the “rule based” system that the West is now so determined to protect was of their own creation following the ravages of the Second World War, clearly intended to safeguard their own interests and the advantages that they enjoyed. As China rises economically and finds itself at the forefront of the technological revolution that is overtaking us, why should it not attempt to regain the place of pre-eminence that it previously occupied? That, from its viewpoint, would be in the natural order of things.

In fact, we should be questioning our own motivation in unthinkingly regurgitating what the West uses to justify its decades of depredations. Incidentally, at the time that China had the leading share of World GDP, we were not far behind at around 24%. There can also be little dispute, given the wealth of information available in the public domain, that the two hundred years of servitude to the British destroyed not just our economy but also the socio-cultural, linguistic and religious bonds that had held the subcontinent together for over a few thousand years. In addition, it now appears that the partition was engineered by the British to safeguard their own interests and much of what ails that region now is but a consequence of that disastrous initiative. The only reasonable explanation for our unstinted support for the West may possibly stem from the fact that we continue to be held in the grip of the “Stockholm Syndrome”.

“We should be questioning our own motivation in unthinkingly regurgitating what the West uses to justify its decades of depredations.” Photo: Thomas Peter/Getty Images

Undoubtedly, over the years, China has viewed India as a potential rival and has successfully used Pakistan as its proxy to ensure that India remains not only severely constrained within the sub continent, but also that its economic development is hampered by petty rivalries and tensions. Not surprisingly the impact of this policy on Pakistan has been no less devastating. Not only is it nothing more than a Chinese vassal, but now also confronts an existential crisis of immense proportions. A sinking economy, deep ethnic fissures and a military that is openly self- serving and refuses to look beyond the humongous profits it derives from its various business enterprises only adds to its problems. It is unlikely that China has as yet fully understood the unintended consequences of its unconditional support to Pakistan. As the situation there deteriorates, it will find itself being increasingly called upon to provide fiscal support for its proxy while simultaneously being subjected to Jihadi rage and frustration that it has had a big hand in creating.

Thus, while China’s zero sum game may have paid dividends in the short term, such an approach can hardly be a credible solution for long term stability or development for any country in the region. It is a given that any armed conflict, involving the three nuclear weapon states, either individually or in tandem, will have serious repercussions for all, with no clear winners likely to emerge since uncontrolled escalation is a distinct likelihood if any of the involved States finds itself facing defeat. Indeed, it seems quite ironic that America now hopes to use India in very much the same manner to constrain Chinese ambitions, with consequences unlikely to be any different than what Pakistan finds itself in.

Apart from the regional issues that haunt us, there is that little matter of the ongoing Sino-American confrontation. Often enough, past actions are a reasonably accurate predictor of future behaviour and in that context this confrontation seems to be proceeding much in the manner in which America treated Japan in the 1930s, once it realised the rapidity with which Japan was catching up with it as a rival. By systematically withholding oil and commerce, it forced the Japanese to undertake a series of offensive actions that not only bogged them down in a confrontation with China, but also forced them to attack the United States and Britain in an effort to stave off economic collapse. All of this despite being fully aware that they would never emerge victorious against American might.

Thus, increasing acrimony over Sino-American trade and tensions in the Persian Gulf, ostensibly between Iran and Saudi Arabia, from where China gets the bulk of its petroleum supplies, is certainly not a coincidence and seems to be following a well-worn path. In a similar vein, the situation in Hong Kong, where locals are agitating for greater democratic rights, ironically something they have never enjoyed ever since the British first set up shop there, seems to be no accident.

All of this is unlikely to lead to a direct military confrontation between America and China, given America’s overwhelming superiority and despite the fact that it is mentally exhausted after twenty years of unproductive wars. However, any conflagration in the Middle East will restrict availability of oil and thereby hurt the Chinese economy, and with that its internal cohesion, as well. In such a situation the only option that may well be available to the Chinese could be to undertake offensive actions against American proxies to send out a warning to the United States against interference in the region, as well as to safeguard its own interests. It is in this context that India may well find itself being dragged into a confrontation that is not of its own making, especially if the Chinese perceive our closeness to the Americans as supportive of their attempts to restrain them. Would it really be in our national interest to be dragged down this path?

There is, of course, the other distinct possibility that Mr. Modi may well be gaming the United States in an attempt to finesse and maximise our negotiating position vis- a- vis the Chinese. If so, it has indeed been a bold and successful ploy but remains only as just another short term gambit in the zero sum game equation. Given these dynamics, it is obviously in the interests of both India and China to adopt a win-win model and make serious efforts at resolving their border dispute decisively and equitably. While conventional wisdom suggests that the Chinese are leaps and bounds ahead of India both economically and militarily, what is often missed out is that in any confrontation in Tibet or in the Indian Ocean, which would be the theatre of operations, the militaries are much more evenly matched because geography favours India.

While for India, a stable and durable friendship with China would help change, if not wholly neutralise, its toxic relationship with Pakistan, for China, it would remove a potential adversary capable of pinning it down to Asia with American assistance. It would require realistic negotiations to overcome decades of hostility and pettiness, to achieve substantive and equitable results. Something that is distinctly possible today given the dominance that both President Xi and Prime Minister Modi exert on the political systems in their respective countries. In this context only time will tell if the recently held informal summit between President Xi and Prime Minister Modi, at Chennai has produced something more substantive than just another photo opportunity for their respective domestic audiences.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Brig. Deepak Sinha (Retd.) was Visiting Fellow at ORF. Brig. Sinha is a second-generation paratrooper. During his service, he held varied command, staff and instructional appointments, ...

Read More +