This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

The Prime Minister of India endorsed “

Surya Nutan” a twin-top solar cooking stove developed by the Indian Oil Corporation (IOC) at the India energy week 2023 in February and announced that the stove will be in 30 million Indian households very soon. The solar cooker is part of the

initiatives taken by the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas (MOPNG) to reduce oil imports and increase domestic production. Other initiatives of MOPNG to reduce oil imports include an increase in the mandate for ethanol blending with petroleum-based transport fuels to 20 percent, an increase in procurement of

compressed biogas by raising the price to INR54/kg from INR45/kg under the

SATAT (sustainable alternative towards affordable transportation) scheme and increase in the production and consumption of hydrogen under the hydrogen mission. As envisioned, if mass adoption of solar cookers is achieved, it will reduce indoor pollution in rural households that burn biomass, reduce consumption of LPG (liquified petroleum gas) which in turn will

reduce the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs), and also contribute to India’s energy security by reducing LPG imports. But will rural households voluntarily adopt solar cookers?

Surya Nutan

According to IOC, the solar cooker is based on a hybrid model designed to use both solar energy and alternative fuels and it is efficient as the design minimises radiative and conductive heat loss. The cost of the solar cooker ranges from

INR12,000 to INR30,000. When manufacturing is scaled up, the cost of the stove is expected to come down. “Surya Nutan” offers a payback time of one to two years assuming an annual consumption of

six to eight cylinders per year per household, according to IOC.

Earlier models of solar cookers required the stove to be outdoors and the cooking process was slow. The cooker could not be used at night, during cloudy days, or when it was raining. The “Surya Nutan” solar cooking system overcomes some of these challenges with the use of

thermal energy storage (TES) that enables cooking indoors and cooking when the sun is not shining. The stove stays indoors while a solar panel collects energy from the sun, converts it into heat through a specially designed heating element, stores thermal energy in a thermal battery, and reconverts the energy for use in indoor cooking. The developers of “Surya Nutan” claim that the stove does not need maintenance for

10 years and the solar panel has a life of 25 years. Unlike batteries that store electrical energy in the form of chemical energy, thermal batteries do not have to be charged adding to the advantages of the solar cooker.

The LPG Challenge

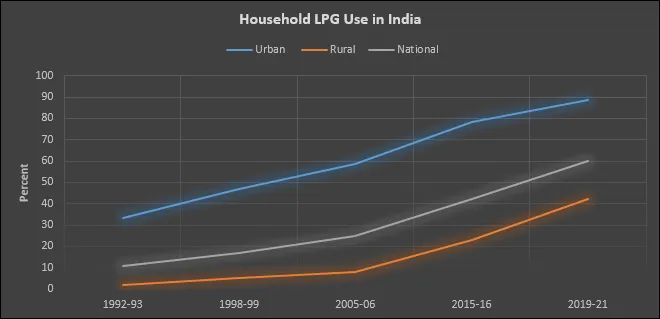

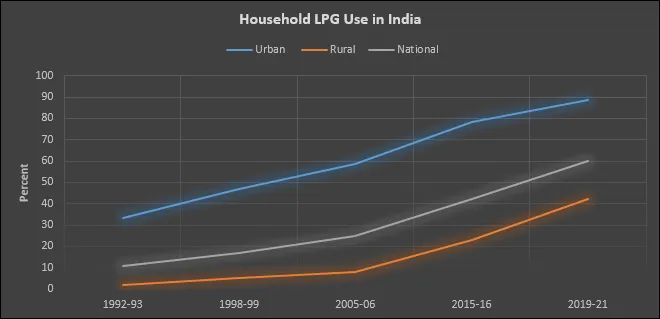

The transition from biomass (firewood) to LPG in Indian kitchens that began in the 1970s is yet to be completed, especially in rural kitchens. However, LPG is the only fuel that has managed to displace biomass as the primary cooking fuel in at least half of rural households. According to the fifth

National Family Health Survey 2019-2021 (NFHS-5) carried out by the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India,

88.6 percent of urban households use LPG or piped natural gas (PNG) as the primary cooking fuel, while

42 percent of rural households use LPG.

Until the 1990s scarcity of LPG meant that only wealthy and well-connected households had access to LPG. When the LPG scarcity eased, a number of

southern state governments launched dedicated programmes for distribution of subsidised or free LPG connections to households that were ‘below poverty line’ (BPL). This substantially increased the number of households with access to LPG in the southern states. This model was successful in galvanising political support for governments dispensing LPG programmes at the state level and was adopted by the centre in the form of the

Rajiv Gandhi Gramin LPG Vitran (RGGLV) scheme in 2009. RGGLV more than doubled LPG dealers in rural areas. In 2016, the current government recast RGGLV with some minor changes and relaunched it as the

Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY).

As in the case of smokeless and improved cookstoves and biogas stoves, initial access to LPG for poor households depends more on

top-down schemes and less on bottom-up decisions and choices available for financially constrained households. However, sustained use depends on family income and behavioural issues such as cooking habits. LPG is minimally invasive as far as cooking habits are concerned and the

shift back to biomass from LPG is associated with financial constraints as demonstrated by the pandemic period.

Incomplete Transitions

In the early years of independence, almost all households used

firewood and dried animal dung as fuel for cooking. The discourse among policymakers over household cooking fuels reflected the priorities of the ruling elite. For the educated

elite planners who formulated policy, household cooking fuel needs were just collateral damage in the larger project of nation-building. Rural cooking fuels were sources of inefficiency and pollution and their use had to be curtailed to allow industrialisation and development to progress. The use of dried

animal dung as cooking fuel was seen as wasteful because animal dung was thought to be more valuable as manure to strengthen food production. Wood used as household fuel was blamed for rapid deforestation by government planners and by environmental groups. One recommendation was that

“social forests” be developed by allocating 50 acres of land per village for the cultivation of fuel wood so as to limit externalities such as deforestation but the plan was not implemented.

In the 1970s and 80s, programmes to distribute

smokeless wood-burning cookstoves to rural households were launched with the same zeal as that demonstrated in the current promotion of solar cookstoves. But it was

not very successful as it did not result in mass adoption and use. Later an initiative to promote biogas generation from cattle dung was launched. As cattle raising was part of every rural household, it was believed that biogas with a stove similar to that of an LPG stove and a high-temperature blue flame would displace the use of biomass and kerosene as the primary fuel for cooking in rural households. In the 1980s about

75,000 biogas units were reportedly operating in the country. However, this failed in the longer term and many biogas units were abandoned. The

high initial cost of the stove (INR9000), financial assistance channelled to farmers rather than women, difficulty in maintaining the biogas units were among reasons cited for the failure. The idea of promoting simple box solar cookers as an option for rural kitchens did not go beyond the pilot and demonstration stages.

Neither the huge opportunity cost in terms of time spent collecting fuel-wood and respiratory disease from nauseous smoke from biomass and kerosene stoves that filled their huts managed to shift choice in favour of smokeless efficient cookstoves, biogas stoves and solar cookers. Decentralised renewable energy solutions for lighting and cooking

shift the technology, even if rudimentary, to the consumers premises. This shifts the burden of maintenance on the consumer. Typically, rural men and women labour in agricultural fields or related jobs during the day. This

leaves little time for maintaining devices such as cookers and solar panels. In other words, the opportunity cost of using solar cookers may be higher than that of LPG stoves. Yet another important issue is the idea of pushing new and somewhat

inconvenient fuels among the rural poor rather than the urban rich. Few leaders will dare to suggest that urban households should shift from LPG to solar cookers in the interest of climate change. It is very likely that rural women want exactly what their urban counterparts have which includes freedom to choose between solar and LPG stoves.

Evidence on outcomes of the use of laboratory-validated improved cookstoves from a large-scale

four-year randomized control trial in India showed that smoke inhalation fell initially but the effect disappeared by year two. There were no changes in health outcomes or GHG emissions. The study found that households used the stoves

irregularly and inappropriately, failed to maintain them, and usage declined over time. One critical insight from the study was that

willingness to pay for reduction in indoor air pollution and the related longer term health benefits was low. Another study that examined

solar stove use in Senegal found that six months after the distribution of the stoves, there was no difference in the amount of time spent cooking near a fire and only a 1 percent decline in fuel use since households continued to use their traditional biomass burning stoves. The key message from the studies is that low carbon technologies must be tested real-world settings where behaviour undermines potential benefits.

Under the climate centric narratives that underpin the proposed shift from LPG to solar cookers, the rural poor are perpetrators of pollution and climate change through their use of biomass/LPG stoves rather than victims of political, economic and social marginalisation that leaves them no choice over fuel use. For alternative energy solutions to succeed, emphasis should be on availability, cost effectiveness and convenience first and pollution control and climate change second and not the other way around.

Source: National Health Survey, various issues

Source: National Health Survey, various issues

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV