-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Ahead of the upcoming COP26 Summit, India needs to redefine its transition path for achieving net zero emissions, and reconsider its dependency on coal

In the run up to the COP26 Summit in Glasgow on 31st October, enthusiasm bubbles over. This is as it should be. Preserving the world as we know it requires cutting back on the 34 giga tons (2018) of annual CO2 emissions, 37 percent of which is by the 16 percent of the global population in high-income economies.

To be sure, income inequality is near universal. Empowered elites, beneficiaries of the “dual economy” syndrome, particularly in developing economies, enjoy “rich world” lifestyles and cannot evade their responsibilities. Pervasive inequality is the rationale for “common” global responsibilities for reversing climate change. But the aspect of “differentiated” responsibilities is just as important, for two reasons. First, it supports differentiating between the higher institutional and fiscal capacity in the rich world to change patterns of fossil energy consumption via technology versus low capacity in the developing world. Second, it reflects “climate justice”, by urging those who have benefited from the near exhaustion of the carbon emissions envelope, to reverse emissions and grow the available emissions envelop.

The salience of “differentiated responsibilities” was visible in Kyoto, 1997. But by Paris 2015, it had morphed into a “free for all” in which we all agreed to go our own ways, with the relatively light, individual responsibility of diligently sharing publicly what we were doing to green our economies—a bit like how divorcing partners treat their past responsibilities.

Over the past six years, the United Nations (UN) system, green activists, concerned citizens, and select industry groups kept alive the need to take more substantive action—an imperative confirmed by the working group for the sixth IPCC Report.

Preparing for Glasgow—the 26th Conference of Parties—the UN advocates that all countries commit to reducing global emissions to 45 percent below 2010 level by 2030, to meet the requirements for limiting temperature rise to 1.5oC and to work towards net zero emissions by 2050.

In the run up to the COP26 Summit in Glasgow on 31st October, enthusiasm bubbles over. This is as it should be. Preserving the world as we know it requires cutting back on the 34 giga tons (2018) of annual CO2 emissions, 37 percent of which is by the 16 percent of the global population in high-income economies.

To be sure, income inequality is near universal. Empowered elites, beneficiaries of the “dual economy” syndrome, particularly in developing economies, enjoy “rich world” lifestyles and cannot evade their responsibilities. Pervasive inequality is the rationale for “common” global responsibilities for reversing climate change. But the aspect of “differentiated” responsibilities is just as important, for two reasons. First, it supports differentiating between the higher institutional and fiscal capacity in the rich world to change patterns of fossil energy consumption via technology versus low capacity in the developing world. Second, it reflects “climate justice”, by urging those who have benefited from the near exhaustion of the carbon emissions envelope, to reverse emissions and grow the available emissions envelop.

The salience of “differentiated responsibilities” was visible in Kyoto, 1997. But by Paris 2015, it had morphed into a “free for all” in which we all agreed to go our own ways, with the relatively light, individual responsibility of diligently sharing publicly what we were doing to green our economies—a bit like how divorcing partners treat their past responsibilities.

Over the past six years, the United Nations (UN) system, green activists, concerned citizens, and select industry groups kept alive the need to take more substantive action—an imperative confirmed by the working group for the sixth IPCC Report.

Preparing for Glasgow—the 26th Conference of Parties—the UN advocates that all countries commit to reducing global emissions to 45 percent below 2010 level by 2030, to meet the requirements for limiting temperature rise to 1.5oC and to work towards net zero emissions by 2050.

Three issues confront India at Glasgow. First, should we announce a net zero target date and, if yes, what should it be? Second, should we commit to a defined transition path to reach net zero? Third, and related to the second, should we announce a date for peaking of emissions— code for abandoning coal as our primary energy source and our most abundant domestic fossil energy source?Preparing for Glasgow—the 26th Conference of Parties—the UN advocates that all countries commit to reducing global emissions to 45 percent below 2010 level by 2030, to meet the requirements for limiting temperature rise to 1.5oC and to work towards net zero emissions by 2050.

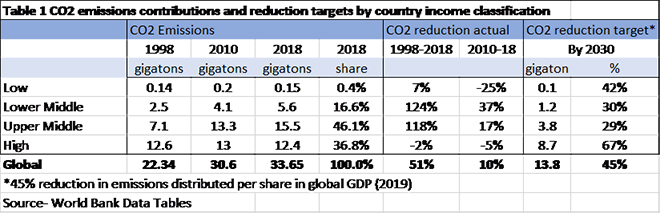

Interestingly, low-income countries—with population share of 8 percent (2019) and per capita income of US $821 (Atlas Method)—reduced their share of CO2 emissions by 25 percent over 2010-2018 as larger countries exited this group. Over 1998-2018, their emissions increased by 7 percent.

High-income countries— with population share of 16 percent and per capita income of US $46,036—reduced emissions over 2010-2018 by 5 percent and over 1998-2018 by 2 percent.

Emissions grew in upper- and lower-middle income countries over both time periods but differentially—less in upper-middle and more in lower-middle economies. The counter factual lesson derived from this differential experience is that economic growth is good for reducing emissions possibly, because it enhances domestic capacity to access better technology and heightens citizen expectations.

Interestingly, low-income countries—with population share of 8 percent (2019) and per capita income of US $821 (Atlas Method)—reduced their share of CO2 emissions by 25 percent over 2010-2018 as larger countries exited this group. Over 1998-2018, their emissions increased by 7 percent.

High-income countries— with population share of 16 percent and per capita income of US $46,036—reduced emissions over 2010-2018 by 5 percent and over 1998-2018 by 2 percent.

Emissions grew in upper- and lower-middle income countries over both time periods but differentially—less in upper-middle and more in lower-middle economies. The counter factual lesson derived from this differential experience is that economic growth is good for reducing emissions possibly, because it enhances domestic capacity to access better technology and heightens citizen expectations.

This was the logic behind the unredeemed pledge at Paris to transfer US $100 billion per year to developing economies for abating climate impact. Higher conditional transfers directly help the recipients. But by enhancing the poor world’s domestic fiscal ability to mitigate climate impact, they reduce the mitigation burden on donors. Table 1 shows why low- or lower-middle-income countries like India, are unable to contribute immediately to emissions reduction. The economic burden is growth retarding, even if distributed per their share in global GDP. Consequently, reduction targets would be double, or more, of the targeted 45 percent for the richest countries. An alternative is to agree a common cap on per capita emissions with differential target dates and disincentives, as a self-regulating, dynamic mechanism to invest in green growth. India's Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) to reduce energy intensity of the economy by 33 to 35 percent over 2005 levels by 2030 is derived from acceptable constraints for green, future growth. It should be tweaked to reflect the new base of 2010.Emissions grew in upper- and lower-middle income countries over both time periods but differentially—less in upper-middle and more in lower-middle economies. The counter factual lesson derived from this differential experience is that economic growth is good for reducing emissions possibly, because it enhances domestic capacity to access better technology and heightens citizen expectations.

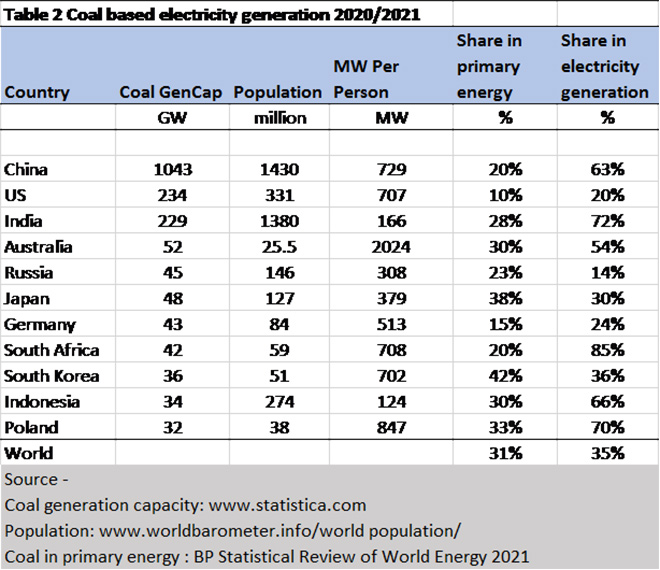

For India, given its dependence on coal for electricity generation, emissions will continue to increase at least till 2040-2050, after which a three-decade long trend of declining emissions can start ending with net zero emissions by 2080.

For India, given its dependence on coal for electricity generation, emissions will continue to increase at least till 2040-2050, after which a three-decade long trend of declining emissions can start ending with net zero emissions by 2080.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sanjeev S. Ahluwalia has core skills in institutional analysis, energy and economic regulation and public financial management backed by eight years of project management experience ...

Read More +