-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Image Source: Getty

This article is part of the series — Raisina Files 2025

In discussing how the world should respond to inequities within health systems and interventions, well-established responses might immediately come to mind: promoting Universal Health Coverage, increasing local primary health care infrastructure and human capital, and addressing social determinants and root causes of ill health. Yet, when considered around the knowledge that health systems are inextricably linked to geopolitics and geoeconomics, the question of how to address inequities becomes appositely centred on how to increase the agency and autonomy of the Global South.

Considerations within this context involve espousing the benefits of relocating the headquarters of global health multilateral institutions to the Global South to better ensure that interventions are developed and delivered with rather than to the communities that global health is intended to serve; moving towards southern-hemispheric sovereignty in the production of medical interventions such as diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics; encouraging and enabling countries in the Global South to fund their own health initiatives and infrastructure; and systematically dismantling the donor-recipient model of global health funding to ensure that countries in the Global South are empowered to step up. Whatever the answers might have once been, today there is a profound sense of January 2025 being a ‘moment of before and after’ in the global health arena. It thus seems pertinent to reconsider this question in the context of what comes after this moment in time. Psychology defines such moments as “significant points in time where a noticeable change occurs, essentially dividing one’s life or situation into a ‘before’ and an ‘after’ phase.”[1] January 2025 as a ‘moment of before and after’ transcends individual, national and cultural perspective and circumstance. It is global and it is seismic.

Although it feels premature for Global Health to have arrived at another pivotal point after which nothing will be the same so soon after the last one, when COVID-19 was declared a pandemic and the world closed down, it is wise to take a moment to survey the terrain in which we now find ourselves. This time, the fulcrum is political rather than pathogenic. Within hours of the inauguration of the 47th president of the United States (US) and throughout the succeeding week, a flurry of new executive orders was signed while other long-standing orders were revoked. It is several of these implementations and revocations that will redefine the global health landscape and create new opportunities for the Global South.

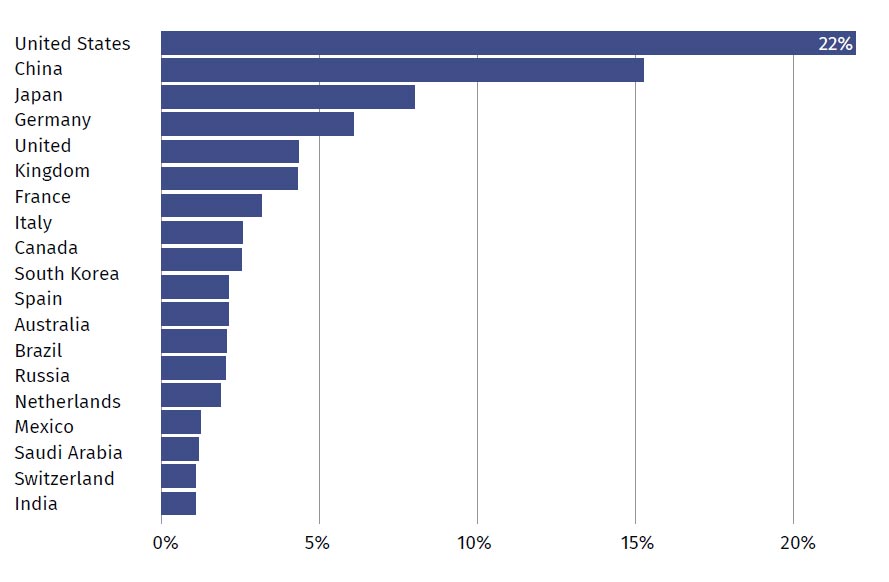

On 20 January 2025, the US Department of Health and Human Services halted all research grant reviews, travel and training for scientists at the National Institutes of Health, the world’s largest public funder of biomedical research with a US$47-billion budget.[2] Federal health agencies including the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were directed to freeze all external communications. On the same day, an Executive Order to ‘Withdraw the United States from the World Health Organization (WHO)’ was also signed.[3] The US contributes around US$1 billion or 22 percent of the organisation’s annual budget of US$6.8 billion. For comparison, the next largest state donor is Germany, which contributes around 3 percent of the total annual budget.[4]

Figure 1. Global Leaders in AI

The US is the largest fund contributor to the World Health Organization Share of mandatory fund contributions from 2024-2025

Source: Reuters[5]

The Secretary of State was ordered to cease negotiations on the WHO Pandemic Agreement and US public health officials were told to stop working with WHO, with immediate effect. This will compromise ongoing investigations surrounding the outbreaks of Marburg virus and Mpox in Africa and the spread of bird flu within the United States and beyond.[6]

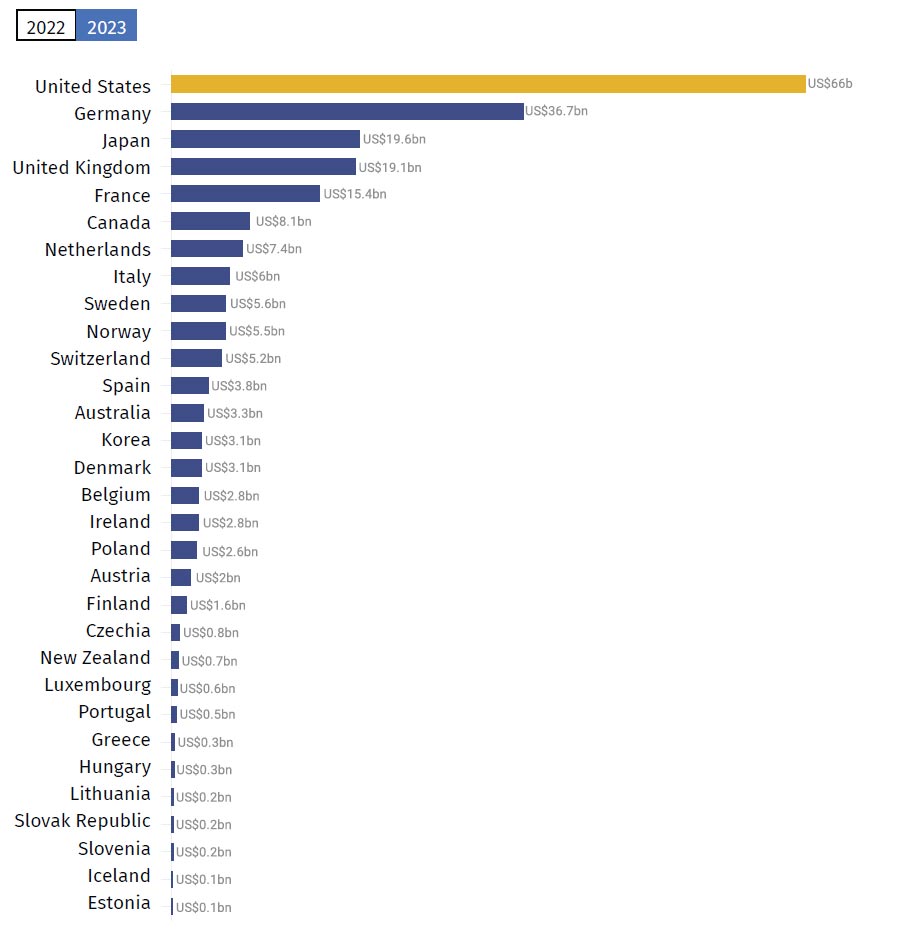

It is not an overstatement to say that these orders alone are enough to alter the global health terrain; yet there were more. The US State Department issued executive orders to pause all new foreign aid spending with immediate effect, as well as a stop-work order for existing contracts and grants.[7] Again, the US is historically the largest donor of Official Development Assistance to the Global South.[8] The latest OECD figures for total development spending shows US assistance of US$66 billion, followed by German assistance of US$36.7 billion.9[9]

Figure 2. Donor Countries’ Total Development Spending (2023)

DAC Donor Countries’ Total Development Spending Total ODA

Source: Donortracker.org[10]

The rationale for these executive orders is stated as the following: “The United States foreign aid industry and bureaucracy are not aligned with American interests and in many cases are antithetical to American values.”[11] The 90-day pause on foreign aid includes funding for the medication needed by 25 million people living with HIV. In the absence of these medications during this time, HIV is likely to develop resistance to current medications, making a re-instatement of previous programmes ineffectual and a worldwide health crisis inevitable.[12]

One might wonder what national values could uphold this course of action and woefully, there is clarity to be found in two further Executive Orders: The order for ‘Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions’[13] revokes 78 executive orders from previous administrations that promote equal opportunities, support underserved communities, and combat discrimination. This, more than anything, radically changes the answer to the question of what the world should do to respond to inequities in access to health interventions and to addressing inequities across all domains.

Federal employees are being urged to report colleagues who fail to comply with this new regime and have been cautioned that those who fail to blow the whistle may face disciplinary action.[14] With multiple pathogens of pandemic potential active around the globe, it makes little sense to foster a culture of cuts and circumspection when collaboration is so desperately needed to reach a pandemic agreement.

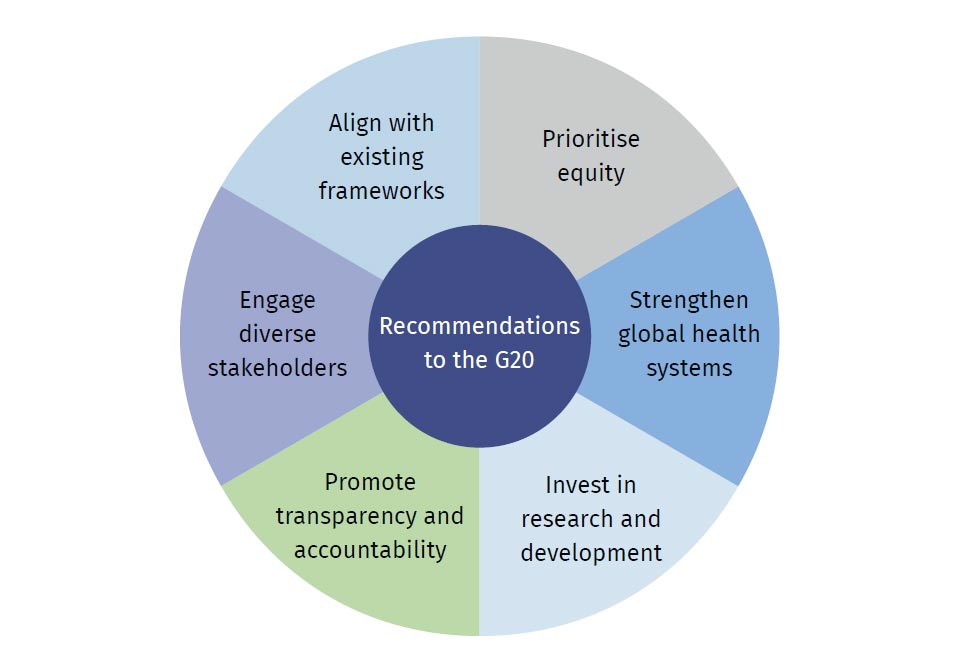

Sound recommendations made by scholars, such as those contained in ORF’s May 2023 policy brief, ‘Preparing for the Next Crisis: The G20 and the Pandemic Treaty’,[15] have been directly undermined by the actions and values upheld by the executive orders listed above. Further delay in reaching an agreement runs the risk of losing the lessons learnt from COVID-19 and the principles of equity and benefit-sharing which were to be embedded in the treaty.

Figure 3. Recommendations to the G20 for Negotiating the Pandemic Treaty

Source: D’Souza et al.[16]

Even though the change of policies is only applicable to federal institutions in the US, researchers fear that federal funding will be used to force universities and other scientific institutions to follow suit.[17] How can the global health community not only prepare for the next crisis but maintain routine health services amidst these developments? How can the global health community broaden the definition of health beyond pandemic prevention to include physical, spiritual, and emotional health outcomes while simultaneously firefighting the most pressing of life-threatening crises with reduced funding and collaboration?

Last year’s Raisina Files upheld “creation and cooperation” as the call of this century; looking back from where we now stand, those words feel prophetic.[18] The editors’ note pointed out that “doomsaying is rarely conducive to transformation, and doomsayers seldom build our futures. Take that line segment, with all its linearity and finiteness, and make it a circle: The more productive Indic notion of Pralaya—the end of one age and the rebirth of another; the deep notion that destruction is intrinsically linked with creation, that every Armageddon is necessarily followed by a Genesis.”[19] The global health community must ensure that this ‘before and after’ moment proves to be a genesis. Instead of it being construed as “the darkest day for global health ever experienced”,[20] every effort must be made to ensure that it is the dawning of an alternative age—the long-awaited epoch of equity.

The disproportionate amount of global health funding provided by the US carried a disproportionate amount of power. With the United States withdrawing from WHO, it will cede this power which can then be re-distributed.[21] This is a moment of geopolitical shift as the US makes itself less relevant to global policies and practices. In response, emerging economies might now put more money into WHO, effect policies and set agendas that were previously opposed by the US.

Indeed, one of the greatest obstacles to reaching a pandemic agreement has been the issue of waiving patenting rights for medical countermeasures so that countries in the Global South are able to gain sovereignty in production rather than relying on inadequate supply chains that are further reduced by nationalism. In negotiations to date, the US and the European Union have stood in opposition to countries in the Global South on this issue. Without the United States taking the contrarian position, there will be a greater chance for more equitable approaches to intellectual property patents and the production of medical countermeasures.[22]

The Global South is rising: India’s G20 presidency demonstrated great leadership in advocating for developing and emerging economies and providing support, in particular, for African nations.[23] The Voice of the Global South Summit in 2023 unified the voices and visions of the 125 countries that participated.[24] In September 2024, China promised African countries US$50 billion in funding and at least 1 million jobs for mutual cooperation in achieving modernisation.[25] Shortly after, Indonesia pledged a US$30-million donation to WHO.[26] Power is shifting hands and that has the potential to create a more just and equitable world in the long term.[27]

It has been nearly 25 years since the African Union governments adopted the Abuja Declaration that set a target of allocating at least 15 percent of national budgets to healthcare improvements;[28] it is also nearly 50 years since the UN General Assembly endorsed the Buenos Aires Plan “to strengthen the capacity of developing countries to identify and analyse together their main development issues and formulate the requisite strategies to address them.”[29] The ineffectiveness of the donor-recipient model of global health funding has long been lamented by countries in the Global South. The radical reduction in aid flowing along the traditional North-to-South access will thoroughly rupture this model and present an opportunity for countries in the Global South to gain control of their own destinies.

These countries have waited a long time. Some three dozen new states achieved autonomy in Asia and Africa in post-war 1960s and ‘70s—these countries, as described by Prabhu (2024), “suffered from multiple challenges in governance, economic security, ensuring political rights, providing access to basic resources and amenities. As expected, the traditional donors looked for avenues to exert influence through a variety of economic, political and social channels, aid being one of them.”[30] If granting foreign aid to these emergent independent states has historically “created pressure, political tensions and economic interdependence,”[31] then a decrease in foreign aid and economic interdependence and the inherent colonial nature of the donor/recipient model ought to then shrink, thereby reducing the hegemonic influence of the Global North.[32] There is a deep and often ignored contradiction within global health as it “was birthed in supremacy, but its mission is to reduce or eliminate inequities globally. To transcend its origins, global health must become actively antisupremacist, and also anti-oppressionist and anti-racist. Equity and justice involve flipping every axis of supremacy on its head.”[33]

It is unclear at the time of writing how many executive orders will be upheld by the legislative and judicial branches of the US government and so speculating on specific outcomes does not offer clarity. In the short term, a withdrawal of US global health funding and foreign aid would undoubtedly cause unimaginable suffering to those whom the funds are meant to support. But to construe the very real possibility of this happening as nothing other than disastrous will not serve us in moving beyond it.

The withdrawal of billions of dollars in US funding may seem like it would create an insurmountable shortfall. However, as total net private wealth is predicted to reach US$629 trillion by 2027,[34] it seems possible that the deficit could be covered by wealth taxes and philanthropic donations alongside increasing contributions from emerging economies in the Global South.

There is a call for philanthropists to “address the inherent power imbalances between funders, nonprofits and the communities they serve”;[35] on the flipside, there is a growing recognition that “chronic underinvestment in health by several African governments has created an enabling environment for African global health practitioners to be significantly dependent on external funding.”[36] There is a need for a meeting in the middle so that increased funding from governments of low- and middle-income countries inspire greater trust from philanthropists and empower global health practitioners in and of the Global South.

Global Health researcher, Lioba Hirsch theorised that equity in global health “means a radical redistribution of funding away from HICs, a loss of epistemic and political authority and a limitation to our power to intervene in LMICs.”[37] She presumed that that this would never happen, but the executive branch of the United States is inadvertently attempting to create the very conditions that Hirsch predicted would generate equity on a global scale while deliberately deeming efforts towards achieving equity within its own borders as radical and illegal. This rollback on civil rights and equal opportunities will embolden those who are sympathetic to the ‘values’ that are being upheld in the Executive Orders so that the current climate in no way assures us of a more equitable distribution of power and funds. Global health leaders will need to be courageous and creative in the face of events yet to unfold. Those in the Global South, in particular, will need to step up and out of learned helplessness.

The end goal of achieving equity in access to healthcare systems requires every global health organisation to consider, “Who controls global health funding? Who sets the agenda? Whose expertise is highly regarded? Who occupies the most influential jobs? Which organisations get funded, where are they located and who leads them? Where are major conferences held? Who gets published in the most influential journals?”[38] We must redress imbalances, reverse unidirectional flow of funding and expertise from the Global North to the Global South, and reject parasitic proposals that seek to merely copy-and-paste health solutions. We must ensure proportional representation of the marginalised majority populations in global health institutions.[39]

For instance, women and girls in the Global South make up 42 percent[40] of the global population and have considerable and consistently reduced health outcomes[41] yet occupy only 2.1 percent of seats on the boards of the global health organisations that purport to represent them.[42] Such marginal representation for women and girls will not achieve equity. There is an imperative to double down on efforts towards ensuring equity and equal opportunity and seek to shatter the “mud ceiling”[43] that hovers over organisations and practitioners in and of the Global South. Mechanisms for internal and external accountability to tackle racism in institutions and funding organisations must be constantly scrutinised and, as far as possible, globalised.[44]

In the new terrain that is spread before us, US actions to distance itself from global health multilateralism creates an opportunity to build a new global health architecture that is owned by, and will benefit the people that it seeks to serve. Countries of the Global South must seek to create growth through empowerment and collaboration and break open like seeds to germinate the genesis of lasting equity.

Endnotes

[1] Robert Evans Wilson Jr, “What’s Your ‘Before This/After This’ Moment?: Critical Events After Which Nothing Was Ever the Same,” Psychology Today, February 12, 2018, https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/the-main-ingredient/201802/whats-your-thisaftermoment

[2] Max Kozlov, “‘Never Seen Anything Like This’: Trump’s Team Halts NIH Meetings and Travel,” Nature, January 23, 2025, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00231-y

[3] United States, Executive Office of the President [Donald Trump], Executive Order 14155: Withdrawing the United States from the World Health Organization, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/withdrawing-the-united-states-from-theworldhealth- organization/

[4] Annika Burgess, “What the US Exit from World Health Organization Means for Global Health,” ABC/Wires, January 24, 2025, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-01-25/donald-trump-executive-order-us-withdrawalwho/ 104850406

[5] Patrick Wingrove, Jennifer Rigby, and Emma Farge, “Trump Orders US Exit from World Health Organization,” Reuters, January 21, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-signs-executive-withdrawing-world-healthorganization- 2025-01-21/

[6] The Guardian, “CDC Health Officials in US Ordered to Stop Working with WHO Immediately,” January 27, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jan/27/cdc-world-health-organization-trump

[7] United States, Executive Office of the President [Donald Trump], Executive Order 14169: Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid, January 30, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/reevaluating-and-realigning-unitedstates- foreign-aid/

[8] World Bank Group Data, “Low and Middle Income,” https://data.worldbank.org/country/XO

[9] Financial Tracking Service, “Total Reported Funding 2024,” https://fts.unocha.org/global-funding/overview/2024

[10] ODA Funding, “How Much ODA Funding Does the US Contribute?,” https://donortracker.org/donor_profiles/united-states#oda-spending

[11] United States, Executive Office of the President [Donald Trump], Executive Order 14169: Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid.

[12] Apoorva Mandavilli, “Trump Pauses Disbursements to Program Supplying H.I.V. Treatment Worldwide,” The New York Times, January 24, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/24/us/politics/trump-hiv-aids-pepfar.html?smid=urlshare& fbclid=IwY2xjawIK-6hleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHboJg-wz1SZxkadP8e0OOVZmTRkYIqpVkkzb8TIZXm7iv TGNTiZkokoTxw_aem_C6cZ1gCMDjhPRwVSBQGANA

[13] United States, Executive Office of the President [Donald Trump], Executive Order 14148: Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions, January 28, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/initial-rescissions-of-harmful-executiveorders- and-actions/

[14] Michael Igoe, “USAID Threatens ‘Disciplinary Action’ in DEIA Crackdown,” Devex, January 23, 2025, https:// www.devex.com/news/usaid-threatens-disciplinary-action-in-deia-crackdown-109136

[15] Viola Savy Dsouza et al., “Preparing for the Next Crisis: The G20 and the Pandemic Treaty,” T20 Policy Briefs, May 23, 2023, Observer Research Foundation, https://www.orfonline.org/research/preparing-for-the-next-crisis-the-g20-and-the-pandemic-treaty

[16] Dsouza et al., “Preparing for the Next Crisis: The G20 and the Pandemic Treaty”.

[17] Amy Feldman, “With NIH In Chaos, Scientists Fear Trump Will Hamstring Critical Medical Research,” Forbes, January 24, 2025, https://www.forbes.com/sites/amyfeldman/2025/01/24/with-nih-in-chaos-scientists-fear-trumpwill- hamstring-critical-medical-research/

[18] Samir Saran and Vinia Mukherjee, Eds., The Call of this Century: Create and Cooperate, Raisina Files, February 2024, Observer Research Foundation.

[19] Saran and Mukherjee, The Call of this Century: Create and Cooperate.

[20] Burgess, “What the US Exit from World Health Organization Means for Global Health”

[21] Amy Maxmen, “What a US Exit from the WHO Means for Global Health,” CBS News Healthwatch, January 24, 2025, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/trump-withdraw-who-global-health/

[22] Maxmen, “What a US Exit from the WHO Means for Global Health”

[23] ET Online, “‘We are the Voice of the Global South’: PM Narendra Modi Highlights India’s Role at ET World Leaders Forum,” Economic Times, September 2, 2024, https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-d&q=https%3A%2F%2Feconomictimes.indiatimes. com%2Fnews%2Findia%2Fwe-raised-our-voice-for-global-south-modi

[24] Ministry of External Affairs Government of India, “1st Voice of Global South Summit 2023,” https://www.mea.gov.in/voice-of-global-summit.htm

[25] Janis Mackey Frayer and Mithil Aggarwal, “$50 Billion, a Million Jobs and a Red Carpet Welcome: China Woos Africa as U.S. Struggles to Keep Up,” NBC News, September 5, 2024, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/china-africa-summit-us-xi-jinping-rcna169673

[26] Antara, “Indonesia Will Provide US$30 Million to Fund WHO Activities, Prabowo Says,” Tempo.co, November 21, 2024, https://en.tempo.co/read/1943783/indonesia-will-provide-us30-million-to-fund-who-activitiesprabowo- says

[27] Maxmen, “What a US Exit from the WHO Means for Global Health”

[28] Monicah Mwangi, “African Governments Falling Short on Healthcare Funding: Slow Progress 23 Years After Landmark Abuja Declaration,” Human Rights Watch, April 26, 2024, https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/04/26/african-governments-falling-short-healthcare-funding

[29] “ United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation, “About South-South and Triangular Cooperation,” https://unsouthsouth.org/about/about-sstc/

[30] Swati Prabhu, “South-South Cooperation in a Post-2030 Agenda World,” Expert Speak, Observer Research Foundation, September 13, 2024, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/south-south-cooperation-in-a-post-2030-agenda-world

[31] Prabhu, “South-South Cooperation in a Post-2030 Agenda World”

[32] Prabhu, “South-South Cooperation in a Post-2030 Agenda World”

[33] Seye Abimbola and Madhukar Pai, “Will Global Health Survive its Decolonisation?” The Lancet 396, no. 10263 (November 21, 2020): 1727-1628, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32417-X/abstract

[34] Nilanjan Ghosh and Swati Prabhu, “Philanthropy as Development Finance: The New Normal,” Expert Speak, Observer Research Foundation, May 18, 2024, https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/philanthropy-as-development-finance-the-new-normal

[35] Ghosh and Prabhu “Philanthropy as Development Finance: The New Normal”

[36] Global Health Decolonisation Movement Africa, “Our Strategy: Coordinated Advocacy,” https://ghdmafrica.org/strategy/

[37] Lioba A. Hirsch, “Is it Possible to Decolonise Global Health Institutions?” The Lancet 397, no. 10270 (January 16, 2021): 189-190, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32763-X/abstract

[38] Global Health Decolonisation Movement Africa, “About Us,” https://ghdmafrica.org/about/

[39] Ali Murad Büyüm et al., “Decolonising Global Health: If Not Now, When?,” BMJ Global Health 5, no. 8 (August 5, 2020), https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/8/e003394

[40] World Bank Group Data, “Low and Middle Income”

[41১] Shaonli Chakraborty et al., “The Role of Gender Equity in Reducing Malnutrition: The View from South Asia,” Observer Research Foundation, August 16, 2023, https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-role-of-gender-equity-in-reducing-malnutrition-the-viewfrom- south-asia

[42] Ayoade Alakija, “Foreword: Global Health 50/50 Report: Gaining Ground?: Analysis of the Gender- Related Policies and Practices of 201 Global Organisations Active in Health,” In Global Health 50/50, 2024, https://globalhealth5050.org/2024-report/

[43] Global Health Decolonisation Movement Africa, “About Us”

[44] Bolajoko O Olusanya, “Correspondence,” The Lancet 397 (March 13, 2021): 968, https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(21)00378-0.pdf

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ayoade Alakija is a Chair, Board of Directors, FIND; Co-Chair, G7 Impact Investment Initiative on Global Health. ...

Read More +