-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The pandemic has offered insights to improve structural flaws in education systems, thus, proper mitigation efforts need to be adopted to reap India’s demographic dividend.

The UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 on Quality Education is recognised as a key driver of economic advancement by significantly influencing health, politics, social empowerment, and human capital as a whole. The role of education was noted to be instrumental for the progress of developing nations and was included as the second Millennium Development Goal (MGD) in 2000 with the objective of achieving universal primary education. The SDG framework took this one step further with the fourth SDG attempting to ‘ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all’.

According to the NITI Aayog, SDG 4 is interrelated with a host of other developmental objectives such as SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), SDG 12 (Sustainable Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Change)—all of which directly or indirectly cater to the human capital inducing aspects of Agenda 2030.

The SDG framework took this one step further with the fourth SDG attempting to ‘ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all’.

Human capital advancement, as envisioned by the SDG 4 objectives, is an integral part of a country’s development, and is the primary force behind economic and societal improvement. The combination of several accumulated skills and goals, of which education stands to be one of the most important factors, also contributes to the enhancement of social capital, crucial for a congenial business climate due to favourable labour market conditions, increased investments and better mobilisation of resources. An econometric analysis, using education data of 55 countries and regions, highlighted a positive correlation between capital investments in education and the economic growth of a nation.

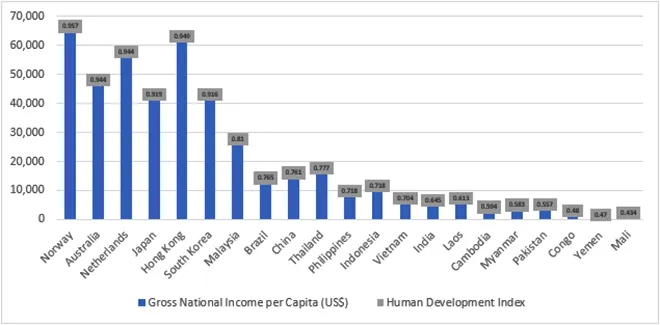

According to the Human Development Report 2020, a clear positive relationship exists between educational outcomes and the Human Development Index (HDI) scores of most nations. Developed nation groups, which are faring well economically as well as in terms of overall human development parameters, have high levels of investment in education, determined through expected and average years of schooling. For example, countries like Norway and Netherlands have HDI scores of over 0.9 while poorer nations like Yemen and Mali languish with HDI scores under 0.5. A high HDI is indicative of nations characterised by higher levels of human capital and economic competency, thus contributing to high per-capita Gross National Income (GNI), as can be seen in the figure below.

Figure 1: Human Development Index (out of 1) and Gross National Income (per capita, US$) of select countries, 2020

Source: Human Development Report 2020, United Nations Development Programme

Source: Human Development Report 2020, United Nations Development Programme

A rise in the average number of years a student spends in school directly contributes to the productivity the person can achieve as part of the labour force. Experts argue that levels of school attainment (secondary, tertiary and so on) have a significant impact on the productivity of a nation’s human capital base. Developing nations have shown better results in receiving stimulus aimed at improving secondary education, leading directly to a positive impact on the nation’s economic growth. Such observations help in determining the targets for investment in developing nations which will have the most efficient results and close the gap with the advanced nations.

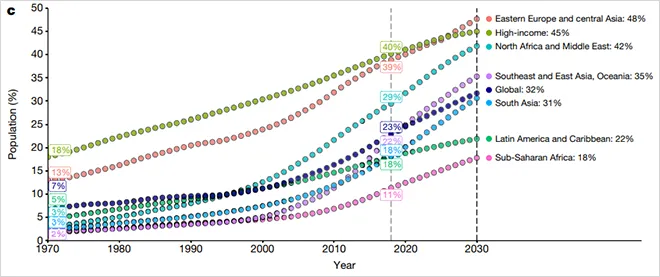

The figure below shows how, since 1970, the number of people with over 15 years of schooling has grown significantly. While significant growth was highlighted for all regions since 2000, Sub-Saharan Africa (with the lowest position in the regional categories) is projected to see a nine-fold growth in schooling levels by 2030. However, the disparities amongst regions continue to surge—developed nations grow at slower rates having crossed most developing nations’ current progress decades ago.

Figure 2: Attainment of 15+ years of schooling: Actual Numbers and Projections

Source: J. Friedman et al., Measuring and forecasting progress towards the education-related SDG targets

Source: J. Friedman et al., Measuring and forecasting progress towards the education-related SDG targets

The pandemic has worsened this divide between the Global North and South. As pandemic-induced restrictions became the norm across the world, schools too had to shut down, impacting the SDG 4 targets. However, certain nation groups were able to open up earlier than others, owing to better health infrastructure and advanced educational facilities. For example, children in advanced economies accounted for a loss of an average 15 days of school in 2020 due to the pandemic. The number increased to an average of 45 days lost for emerging-market economies, and the value stood at 72 for children in the poorest nations. Oceania and the European nations fared far better than the rest of the world when it came to weeks of education lost to lockdowns. Mitigating the divergences between the developed and the developing world, in terms of these losses, has become extremely crucial in the post-pandemic recovery processes that determine the long-term macroeconomic structure of the world economies, with human capital being the most crucial component.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) further points out the areas that require attention to smoothen the transition from the pandemic era in consonance with the impact on students’ psychological health and overall development.

Whilst education has taken a major hit, the pandemic offers insight into how systems can be adapted to improve upon existing structural flaws. Whilst physical access to educational institutions had prevented students from attending schools during the pandemic, the focus on improving telecommunication and internet penetration in remote areas is seminal. This, when paired with better access to affordable technology, would improve universal access to education in the post-pandemic world.

Whilst on one hand public funding needs to be deployed to bridge the demand-supply gap that prevents the digitisation of the education system, on the other, remote learning infrastructure has to be established to make sure that education outreach does not fall behind for the developing and underdeveloped world. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) further points out the areas that require attention to smoothen the transition from the pandemic era in consonance with the impact on students’ psychological health and overall development.

The importance of SDG 4 on the economic outcomes of a country can thus not be understated. Whilst the pandemic has had a dampening effect on the education and skill acquisition frameworks across countries, the mitigation efforts are extremely crucial not only for socio-economic progress but also to effectively harness the demographic dividend for emerging economies like India.

The author acknowledges Rohan Ross at NLSIU, Bengaluru, for his research assistance on this essay.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Soumya Bhowmick is a Fellow and Lead, World Economies and Sustainability at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy (CNED) at Observer Research Foundation (ORF). He ...

Read More +