Draft amendments to the Electricity Act 2003 (EA 2003) in the Electricity Amendment Bill 2014 (EA 2014) suggested, among other things, the separation of carriage and content, with the goal of increasing consumer choice in electricity procurement and promotion of renewable energy (RE) based electricity consumption. The separation of carriage and content meant separating the distribution and supply function that was expected to promote competition in electricity retail. RE-based electricity promotion in EA 2014 included a number of incentives at the supply end, along with complementary provisions at the demand end. Under EA 2014, RE-based electricity generation and supply would not require a licence, and cross-subsidy for open access would be eliminated.

Although EA 2014 is yet to become law, the provisions of EA 2003 that were prerequisites for introducing competition at the retail end have not yielded the expected results. Open access is faltering because of high cross-subsidies and a lack of infrastructure. The parallel distribution licensee model has also failed to pick up, as it requires distribution companies to distribute power “through their own distribution system within the same area.” This means duplication of capital-intensive infrastructure leading to higher costs. The distribution licensee model adopted in Mumbai stands as testimony to this outcome.

The parallel distribution licensee model has also failed to pick up, as it requires distribution companies to distribute power “through their own distribution system within the same area.”

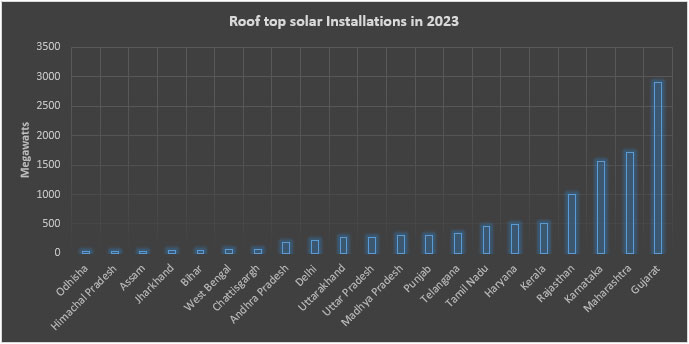

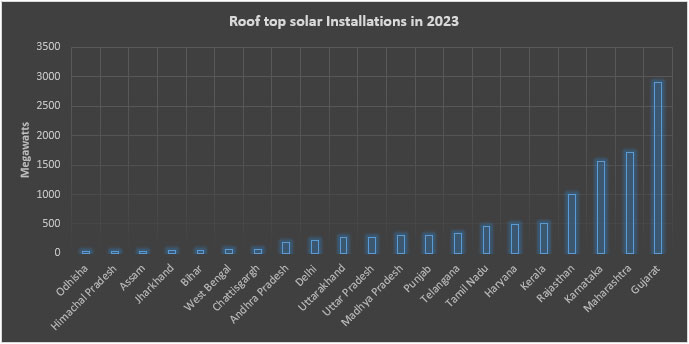

In this context, distributed production and consumption of RE by households and industries, primarily using solar photovoltaic (PV) systems, is projected as a potential driver of RE generation and consumption. In 2023, the cumulative capacity of roof top solar PV installation capacity was 10 GW (gigawatts) which was about 7.5 percent of total installed capacity of RE and 13.8 percent of the total solar installed capacity in November 2023. In India, over 75 percent of rooftop installations are by commercial and industrial entities. Those with solar rooftop installations are both producers and consumers of RE and can drive RE adoption with the support of the right infrastructure and financial incentives provided by distribution companies (discoms). However, caution is recommended as this option may impose costs on the economically challenged households in India.

Incentives for Prosumers

Prosumers are end-use consumers of electricity who also produce their own electricity at the point of consumption to meet their own electricity needs and export surplus electricity to the grid. Increasing the number of prosumers could boost RE consumption and also substantially reduce transmission and other system losses. These potential benefits are particularly important at the city level, where a large share of electricity is consumed, and where consumption is set to rise with rapid rates of urbanization. The major policies that enable the development of prosumers are capital subsidies for installation of solar PV systems, net-metering and feed-in tariffs (FiTs).

Capital subsidies allow middle-class households and small commercial and industrial entities to adopt solar roof-top systems. Net-metering which is the most lucrative billing system for prosumers, allows customers (residential, commercial and industrial) who generate their own electricity from solar power to feed electricity they do not utilise into the grid. Under net metering, the value of electricity the prosumer feeds into the grid is the same as the value of electricity the prosumer imports from the grid. The bill calculation is based on the net value. The net present value (NPV) of a net-metered system is high; a prosumer under net metering does not require investment in a storage system, and a solar PV system with net metering has a short payback period. In India, policy on net metering varies from state to state. Net billing is similar to net metering, except that the tariff for electricity exported to the grid is lower than the tariff charged for electricity used from the grid. In a gross metering system, the prosumer does not directly use electricity produced by solar panels. Instead, the electricity produced is exported to the grid, at a fixed rate (FiT), and the prosumer draws electricity at the tariff charged by the discom like most other consumers. Though gross metering reduces the prosumer’s savings, it offers an incentive to the discom to induct prosumers into the distribution system. From a purely economic perspective, net metering could overvalue the prosumer’s electricity supply, but from a climate action perspective, this valuation may be justified on the grounds that it promotes the decarbonisation of the electricity grid.

Challenges

There are many barriers to the expansion of solar PV prosumerism in India, including high initial costs, insufficient support mechanisms and legal frameworks, resistance by incumbent discoms to provide support, inadequate levels of training and skill of technology providers, poor information, and a host of administrative or financial barriers. Subsidies for the production and use of solar PV can overcome these barriers, but there are limits to subsidising RE adoption, as the case of Spain shows. In the late 2000s, Spain implemented generous support for RE adoption. Under this support mechanism, the prosumer was able to choose between selling electricity generated with solar PV under a FiT mechanism or selling it in the free market that offered market price plus a feed-in premium. This increased solar roof top adoption substantially. However, in 2012, this support scheme was suspended as payment to prosumers exceeded expectations. In 2016 and 2017, the government called for technology agonistic RE auctions. Wind power won as it sought no additional premium apart from the market price. In 2015, Spain imposed a “sun tax,” under which systems up to 100 kilowatt (kW) were not allowed to sell surplus electricity to the grid, and systems above 100 kW required registration to sell to the spot market.

Subsidies for the production and use of solar PV can overcome these barriers, but there are limits to subsidising RE adoption, as the case of Spain shows.

The speed and degree of prosumer growth may be influenced by several economic and non-economic factors. In India, the growth of prosumerism could be motivated purely by the economic self-interests of end-users to reduce their costs of energy and constrained only by defined limits to the logistic growth of technological expansion. Affluent urban households that imitate the lifestyle and ideologies of the West could initiate grassroots movements motivated by increasing urgency for climate action, facilitating neo-communal prosumerism. Other drivers for export-oriented services and industries to become prosumers could include compulsion to turn green to navigate trade barriers imposed by developed countries.

The increase in the number of prosumers in the electricity system brings a host of challenges to discoms, the most significant is loss of revenue while maintaining investment in grid security and stability. The impact of growing number of prosumers on reliability and resilience raise concerns. This means additional investment in monitoring, forecasting, aggregation, automation, and control. This is a challenge for financially challenged discoms.

A recent paper reviews the idea of a “death spiral” for discoms, where electricity consumers self-sort to become prosumers, thereby leaving consumers who are financially unable to convert to prosumers bear increasing energy costs pushing more consumers to become prosumers, which drives the price up further. In India, the poor without proper homes with roofs, home renters with no access to space for PV systems, and those who cannot afford PV systems would have to bear the cost of prosumerism. The irony to note here is that consumers who cannot afford to become prosumers pay prosumers to sustain the attraction of prosumerism. Another study on the Spanish case found that most prosumers will not disconnect from the grid, even when they have installed back-up systems and are able to meet their consumption needs comfortably when the incentive system for selling green electricity to the grid are attractive. Prosumersim is in a nascent stage in India. This provides an opportunity for India to weigh the costs and benefits of prosumerism and adopt a model that is relevant for Indian social and economic conditions. Given that residential PV generation is much more expensive than utility-scale PV generation, the subsidy cost per kWh (kilowatt hour) of residential PV generation is substantially higher than the per-kWh subsidy cost of utility-scale PV generation. There is no compensating difference in benefits and thus there is simply no good reason to continue to provide more generous subsidies for residential-scale PV generation than for utility-scale PV generation. Policies for supporting RE generation and consumption need not offer higher subsidies for rooftop residential PV systems than utility-scale PV generation. What is required is a system for recovering distribution costs of discoms that reflects network users’ particularly prosumers’ impacts on those costs.

Source: Ministry of New & Renewable Energy; Note: Only states with installed capacity above 10 MW are shown.

Source: Ministry of New & Renewable Energy; Note: Only states with installed capacity above 10 MW are shown.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV