Maternal health and well-being has remained a neglected aspect of our political discourse

The relationship between a mother and her child is beyond words and description. But it is unfortunate that not every mother is able to live with her newborn and not every child is blessed with mother’s love.Maternal deaths, in many ways,mirrors our health system and is a sentinel indicator of our development.

Given its relevance, the United Nations Millennium Declaration warranted achieving a 75% reduction in maternal mortality from 1990 to 2015 but several nations, including India (68.7% reduction), were still behind target. Such limited success has re-focused global attention with maternal mortality reductions being stated as a prime target under the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).There is a wide acknowledgment that maternal deaths are almost entirely preventable but the extent to which we fail to do so reflects our underperformance as a society and a nation.

Maternal mortality in India

The burden of maternal deaths is usually reported as maternal mortality ratio (MMR) defined as the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. United Nations expert group estimates that in 2015 India had a MMR of 174 implying that each year 45,000 women die due to causes related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management. After Nigeria, India is the second largest contributor to global burden of maternal deaths accounting for 15% of the total 303,000 maternal deaths worldwide. India’s MMR is six times higher than China (MMR 27).

MMR in poll bound states

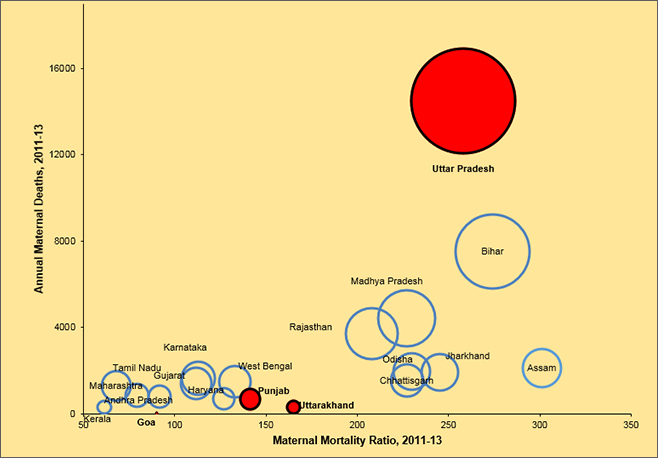

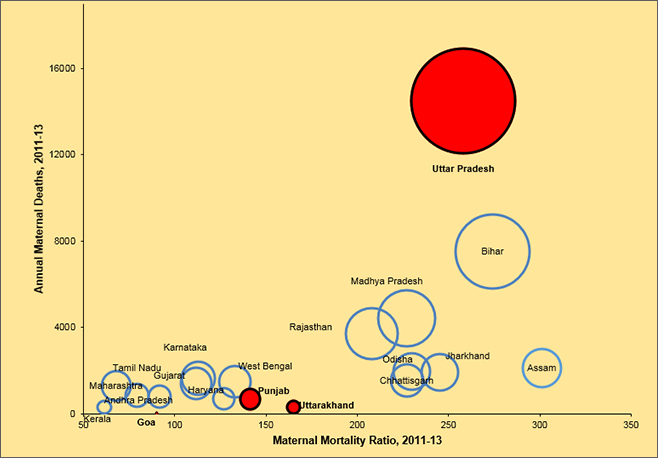

How is the burden of maternal deaths distributed across poll bound states? According to the latest round of Annual Health Survey, during 2012-13,Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Uttarakhand had an MMR of 258 and 165, respectively whereas Punjab had an MMR of 141. With over 14,500 maternal deaths,UP alone accounts for one-third of the total maternal deaths in India. Punjab and Uttarakhand contribute to over 600 and 300 maternal deaths, respectively. We do not have official numbers for Goa and Manipur. However, a Goa Medical Collegestudy suggests Goa’s MMR to be in the range of 90 which translates into 21 maternal deaths each year.

Figure 1: MMR and annual burden of maternal deaths across major states

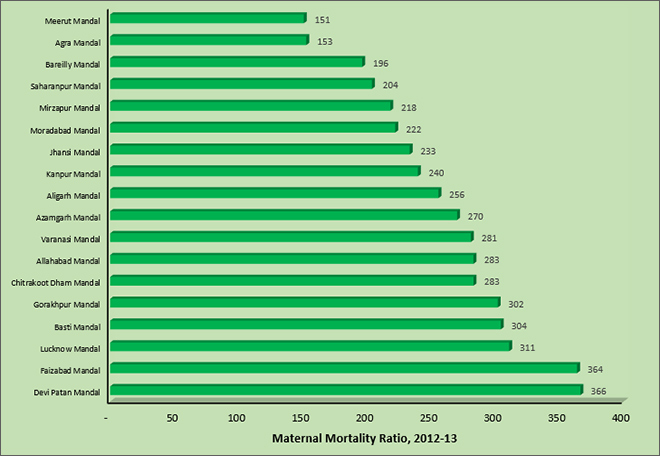

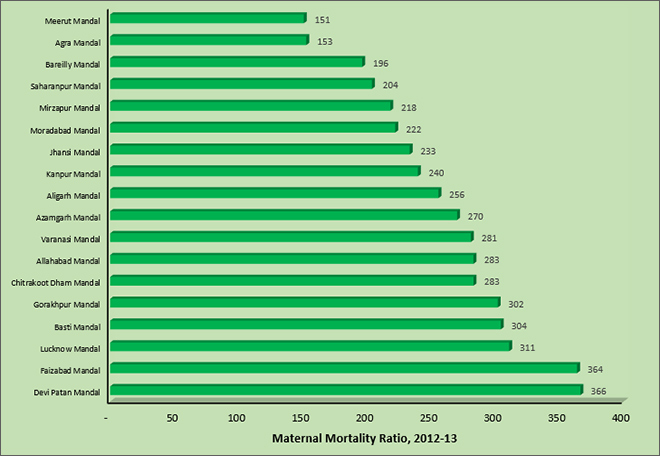

Figure 2: MMR across administrative divisions (Mandals) in Uttar Pradesh

Does place of residence matter in UP?

It is indisputable that UP is the battlefield if India has to improve its odds of meeting the SDGs in maternal health. But there are numerous challenges including huge Mandal-specific disparities. MMR within UPranges from 151 in Meerut Mandal to 366 in Devi PatanMandal. More than five Mandals from Central and Eastern UP, including the Lucknow Mandal, have MMR of more than 300 whereas Mandals from western region report lower MMR. These disparities are deeply rooted within social, cultural and economic divide where women from marginalized communities find themselves at an elevated risk of maternal mortality.

Progress toward the SDGs

Punjab took a decade to decrease MMR from 178 in 2001-03 to 141 in 2011-13.However, during the same period UP/Uttarakhand were able to reduce MMR from 517 to 285. These comparisons suggests that at low levels of MMR it becomes more of an achievement to reduce it further. The effect is visible from data for 2010-11 and 2012-13 which show that UP’s MMR declined from 345 to 258 whereas during the same period Uttarakhand witnessed much slower reductions (188 to 165). Because of higher base levels UP continues to gain rapid absolute reductions but Uttarakhand and Punjab are found struggling to reduce MMR below 100. Given such nonlinear pace of improvements it will be increasingly difficult for these states, particularly UP, to achieve the SDGs target of reducing MMR to below 70 by 2030.Interestingly, Kerala and Maharashtra have already achieved the national SDGs target with Tamil Nadu all set to join the club.

A first step to reduce maternal deaths

Institutional care in the presence of skilled birth attendants is a prerequisite for ensuring rapid reductions in maternal mortality. There are pockets inUP, Uttarakhand and Manipur with high home-based births. Reports show thatUP and Uttarakhand have 42% and 41% home-based births, respectively. Hilly districts of Chamoli, Bageshwar, Rudraprayag and Tehri Garhwal have over 50% home-based births. In this regard, Manipur’s profile is similar to Uttarakhand but Punjab and Goa are better-off because of favorable social, economic and health system related factors.

Complementing Institutional Care

With advances in scientific knowledge and proven clinical interventions, it is possible to prevent most of the maternal deaths. But we have to addressthe delays 1) in decision making and care seeking at the household level, or 2) in arranging transport and reaching the health facility, or 3) in receiving appropriate care at the health facility. About 50% of maternal deaths in India occur at home, 14% during transit, and 36% at the health facility. Policy efforts are warranted to address thesethree-delays by improving awareness, transport infrastructure and emergency care.

With high levels of anemia and undernutrition, it is necessary to have a good network of facilities with emergency obstetric careincluding blood transfusion and C-section. But such services are clustered in urban areas and there are several districts across UP and Uttarakhand who fail to provide timely emergency care (EmOC). Districts often struggle to ensure complete EmOC staff (Gynecologists, anesthesiologists and surgeons) in regions with poor amenities. Clearly, the hardware of physical infrastructure is of no use in the absence of trained doctors.

Economic growth, high public health expenditure and improvements in female literacy can go a long way in reducing such eventualities. Chronic poverty and undernutrition- which the former Prime Minister branded as a national shame – are often the fundamental causes of maternal death.All these are inter-linked factors that partly showcases our economic capabilities but in part reflects social attitude towards gender equity and empowerment.

The tribal population as well as other marginalized communities are specifically disadvantagedin these factors. Field studies in Uttar Pradesh show that staff corruption and discriminatory treatment often compromise access to quality care for the poor and marginalized. Therefore, improved health system responsiveness and attitude is clearly the need of the hour.

Policies and best practices

Two major initiatives under the National Health Mission (NHM) – Janani Suraksha Yojana and Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram – directly aim to incentivize beneficiaries to avail delivery care services at health facilities. There is also a rich bouquet of best practices from other Indian states that can be adopted by poll bound states, particularly UP, Uttarakhand and Manipur. For instance, Gujarat has worked with the private sector under the Chiranjeevi Yojana to improve levels of institutional delivery. Rajasthan provides free drugs and diagnostics service to all.

Tamil Nadu has several unique features such as streamlined health administration with effective public health cadre, robust maternal mortality surveillance system, well-planned emergency care transport services, good public procurement of drugs and supplies. Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddy Maternity Benefit Schemein Tamil Nadu provides aconditional cash benefit of Rs.12,000 to each beneficiary women for uptake of antenatal care, institutional delivery, and child immunization. In this context, the Prime Minister’s decision to introduce a nation-wide scheme for financial assistance of Rs. 6000 to pregnant women is expected to help reduce maternal mortality in a big way. Clearly, this has budgetary implications but with effective planning these poll bound states can emerge as a role model in provisioning of good health at low cost.

Message for poll bound states

Demonetization proved that we keep a good account of our money but apparently we lack expertise and motivation in counting maternal deaths, most of which are entirely preventable. Regular and comprehensive data on maternal deaths disaggregated by place of residence, caste, class and religion can help to comprehend the varied dimensions of the problem. It is imperative that the public administration should improve maternal death reporting via health management systems and civil registration systems (CRS). Though the CRS is reasonably good in Goa and Punjab but it is severely challenged in UP, Uttarakhand and Manipur.

Given the magnitude of the problem, the international and national organizations are rightly concerned about achieving faster reductions in maternal mortality. In this regard, Prime Minister’s recent commitment to launch a financial assistance scheme for mothers further increases the relevance of safe motherhood as a policy objective. However, our state health systems currently follow a uniform operational strategy to improve maternal and child health and which is fundamentally an extension of NHM umbrella. Though from the perspective of central government it makes sense to provide a broad framework but instead of turning the centre’s approach into a one-size-fits-all label, the states should adopt a spirit of innovation to devise context specific policies to achieve SDGs in health.We also have a shared responsibility of motivating the policymakers to invest adequate resources in health, particularly for recruitments and development of emergency services in neglected areas.

In conclusion, it is worth reiterating what Prime Minister Modi remarked on New Year eve that, “when policies and programmes are made with clear objectives in mind, not only are beneficiaries empowered, but both short term, and long term benefits are achieved”. It is one thing to understand the importance of healthy mothers but it is also time that we appreciate this fact as voters and citizens and make a difference.

William Joe is Assistant Professor, Institute of Economic Growth, Delhi.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV