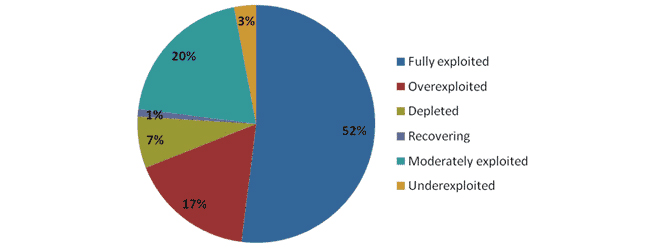

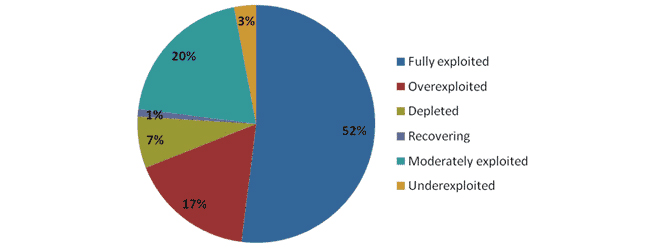

A study conducted by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) finds out that out of the 600 marine stocks monitored globally, 52% have been fully exploited against a meagre 3% of underexploited fish stock. Mechanised trawlers stand as one of the prominent reasons for depletion of the Indian marine ecosystem. In 2015, the Sri Lankan authorities had claimed to have spotted 40,544 Indian trawlers in their territorial waters, touting them to be solely responsible for the dearth of resources in the Palk Bay region.

The ethnic commonality of Indian and Sri Lankan fisher folk is harmoniously celebrated by these two marine allies. However, frequent poaching in the disputed waters of Katchatheevu, a 285-acre uninhabited island, a rich fishing ground located in the Palk Bay region, has become a source of major conflict between them. One of the reasons of this conflict emerges from the presence of Indian trawlers at the Sri Lankan side of the Palk Bay. Tamil Nadu has 5,887 registered mechanised boats (as of March, 2016) and 4,500 registered trawlers, half of which, depend on Sri Lankan waters for their catch, after having rummaged all resources on their side of the bay.

Trawlers are a source of peril to the Sri Lankans because of their capacity to destroy wide areas of the seafloor. So as to curtail their existence in the bay, bottom trawling must first be regimented. In 2006, the United Nations General Secretary reported that 95 percent of damage to seamount ecosystems worldwide is caused by deep-sea bottom trawling. One of the prominent reasons for such a sweeping impact of this technique is its unselective behavior. Due to a high by-catch to total catch ratio, the practice causes detrimental harm to non-targeted species, and more so to juvenile fish species. Approximately 1,000 by-catch deaths of marine species are witnessed every day through bottom trawling.

Source: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)

Source: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)

The genesis of this Indo-Lankan conflict dates back to late 1960s when the potential of harvesting shrimp resources in the Palk Bay region along with the acquisitiveness for earning foreign exchange from markets of Europe, United States and Japan was realised. The motorised trawlers gradually increased, replacing the old fishing crafts.

Domestic governance: The India-Sri Lanka outlook

Since pervasiveness of deep-sea trawling emerges as one of the impetuses towards the convolution of the fishing rights dispute in Palk Bay, it is believed that the contested issue of demarcation of the mutually acceptable international maritime boundary line (IMBL) would reach a substantial resolution only once the existing trawling fleet is downsized in the region.

In a move to restrict Indian trawlers in the area, the Sri Lankan Parliament (SLP) promulgated a ban on the practice in July 2017 by unanimously passing an amendment to the Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act, along with an increase in fines on foreign vessels found poaching in the country’s waters, by passing an amendment to the Fisheries (Regulation of Foreign Fishing Boats) Act, 1979.

While this legislative moves are obviously targeted against the Indian fishing fleet, they have caused collateral damage to Sri Lanka’s own interests too, as curbing the disparaging impact of bottom trawling has also affected the livelihood of over 2.5 million fishermen, who, as per the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, contributed a share of 1.3 percent to the GDP in 2016.

Alternatively, the Indian government has smartly envisioned a path of regulations over an absolute bar on the practice. With deep-sea fishing being considered as an alternative to bottom trawling, the Centre, under its Neel Kranthi Mission (‘Blue Revolution Scheme’), launched a three-phase (2017-2020) project, to make trawlers switch over to deep-sea tuna long-liner-cum-gill netter boats, a measure expected to provide an alternative source of livelihood to fishermen communities, along with unlocking a potential of 1.7 million tonnes of underexploited and unexploited fish. With Tamil Nadu having a total of 608 marine fishing villages as of 2015, and supporting close to 12 lakh fisher folk (9.64 marine fisher folk and 2.28 inland fisher folk), India could have certainly not afforded this huge loss of livelihood of fisher folk as well as to the industry that contributes1.07 percent to the national GDP, with the present fish production standing at 6.4 million metric tonnes.

A 2015 report suggested how the use of tuna long-liner-cum-gill netter boats could change the fishing method of Rameshwaram fishermen, thereby reducing their arrests by the Sri Lankan Navy. In 2015 alone, 70 trawlers were confiscated with a prosecution of over 450 fishermen. At least 100 deaths were reported in the same year on account of poaching into Sri Lankan waters. While gill nets and long-liners too have their respective shares of impact on the seabed, one of the studies of the International Council for the Exploration of the Seas (ICES) finds that bottom trawl fishing stands out as the most detrimental to deep-water corals and other vulnerable species, diminishing marine diversity and productivity.

National Policy on Marine Fisheries

Aiming to replace as many trawlers as possible, the Indian Government adopted the National Policy on Marine Fisheries (NPMF) in 2017. While seeking to encourage entrepreneurship and public-private partnership in marine fisheries sector, the policy overlooks sea security, an integral part of the social security and development of fishermen and their vessels. It falls short of addressing the real problems of small coastal fishermen. The deterioration of our territorial sea and exclusive economic zone (EEZ) at the hands of the first-come first-take principle wasn’t enough that this policy has further brought in relegation of fisheries management and non-delineation of access rights to marine resources. NPMF only adds fuel to the fire by intending to put private investments in deep-sea fishing at the forefront, thereby allowing back door entry for foreign players, and conveniently ignoring the aspect of protection of small artisanal fishermen and fisheries management.

The international diaspora on fisheries conservation is strongly endorsed by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG 14) which advocates elimination of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing practices. The Council of the European Union revised its legislation in June 2016, imposing a ban on deep sea fishing by bottom trawlers below 800 meters in European Union and Fishery Committee for the Eastern Central Atlantic (CECAF) waters. Countries like Brazil, Chile, Germany, the Netherlands, and South Africa along with most Pacific island nations too stand in stern opposition of the practice. However, with bans inviting loss of livelihood of stakeholders, it is vital to introduce a much pragmatic and holistic alternative prior to pronouncing an enforcement measure.

Many a times, countries embrace unsustainable forms of fishing to meet the exigencies of foreign markets. More often than not, the jeopardy of these reckless techniques are ignored. Changes in terms of introducing scientifically-tested technology, capable of combating the high by-catch to total catch ratio, could be brought in, along with timely modifications of existing fishing gears for their contact with the seafloor. The need for greater people-to-people ties between the two nautical neighbours was pressed during Prime Minister Modi’s meeting with the Sri Lankan Parliament (SLP) delegation, where the sentiment once again failed to include the fishermen communities. While the Indian government is successfully diverting its fisher folk towards deep-sea fishing, the fate of coastal fishermen stands dicey. A mechanism concentrated solely on new technology which proliferates private sector participation hampers the welfare of artisanal fisher folk. Cross-country partnerships on conservation of marine ecosystem could procure sturdy benefits, while also maintaining the sanctity of international obligations, if only adopted jointly by India and Sri Lanka.

Ritika Kapoor is a Research Intern at Observer Research Foundation, Mumbai.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations)

Source: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) PREV

PREV