-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement is an opportunity to reconfigure climate finance and create an equitable and stable ecosystem using public, private and philanthropic capital

Image Source: Getty

The recent withdrawal of the United States (US) from the Paris Agreement has created a significant gap in global climate action. Just months ago, the US at COP29 pledged a significant amount to the new US$300 billion climate finance goal, signalling a renewed commitment to tackling the climate crisis. This abrupt reversal not only undermines collective efforts to combat climate change but also raises critical questions about the stability of global climate finance.

The Paris Agreement seeks to address this imbalance through the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR), urging the Global North, as the largest polluters, to shoulder a greater share of the burden.

Finance is central to enabling transformative climate action, whether through renewable energy projects to reduce emissions, or initiatives that bolster resilience in infrastructure and agriculture. This is particularly crucial for countries in the Global South which bear the brunt of the climate crisis but lack the financial bandwidth to address it. This inequity is stark: developing countries contribute the least to global emissions yet face the most severe consequences. The Paris Agreement seeks to address this imbalance through the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities (CBDR), urging the Global North, as the largest polluters, to shoulder a greater share of the burden. However, repeated failures to meet financial commitments have widened the climate finance gap, leaving vulnerable nations increasingly exposed to climate risks.

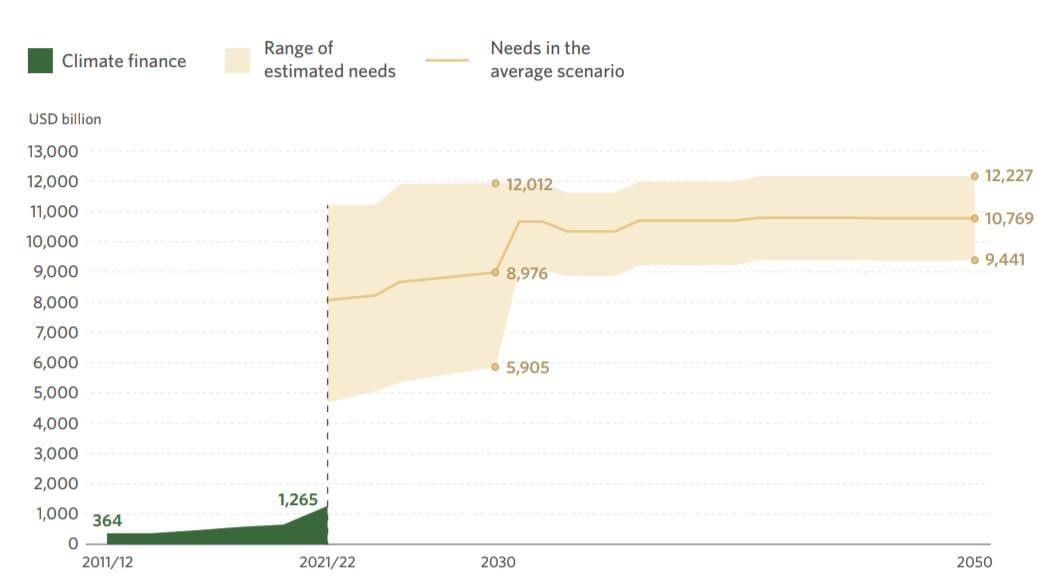

Figure 1: Global tracked climate finance and estimated needs through 2050

Source: Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), 2024

Beyond the shortfall in funds, the quality of climate finance also remains a pressing concern. In 2023, 67 percent of public climate finance was allocated to mitigation efforts, leaving only 33 percent for adaptation. While reducing emissions is vital, the transition to net zero is lagging far behind the escalating impacts of climate change. For instance, while Guyana aims for net-zero emissions by 2050, its capital, Georgetown, is projected to be submerged by 2030. Adaptation, therefore, becomes equally, if not more urgent. However, adaptation efforts often struggle to attract funding due to their perceived lower economic returns compared to mitigation projects, perpetuating the cycle of vulnerability in the Global South. Moreover, the dominance of loans over grants in climate finance further burdens already debt-ridden developing nations, undermining the very principle of climate justice.

The existing financial imbalance underscores a deeper systemic failure in global climate governance, calling for a strategic overhaul to scale up climate finance—both in quantity and quality.

The existing financial imbalance underscores a deeper systemic failure in global climate governance, calling for a strategic overhaul to scale up climate finance—both in quantity and quality. However, amidst this setback lies an opportunity to reimagine and fortify global climate finance architecture. Can the US withdrawal serve as a wake-up call to address the systemic inefficiencies in climate finance? How can developing economies, which bear the disproportionate brunt of climate change, secure the necessary funds to build resilience? Most importantly, how can the world move beyond the broken promises of the past and chart a more inclusive, sustainable future?

Firstly, despite the US withdrawal and limited availability, public finance still remains a critical component of global climate finance. It serves as an essential catalyst for de-risking private investments through policy guarantees, subsidies, and concessional financing. Initiatives such as green bonds, sovereign sustainability funds, and blended finance mechanisms are crucial in mobilising resources. For instance, India's Sovereign Green Bond initiative, which raised over US$2 billion in 2023, demonstrates how public policy can crowd in private capital. Therefore, governments must step up their role in creating an enabling environment that attracts investments to leverage climate finance. Apart from the issue of climate justice, developed countries also have a vested interest in addressing climate impacts. In 2023, greenfield investments surged by 22 percent, with 60 percent of the mega projects concentrated in developing Asian economies. The Global South’s total export value reached US$53 trillion in 2022, driven by its pivotal role in global supply chains. However, climate-induced disruptions, such as the severe drought in the Panama Canal in 2022, caused major disruptions to maritime routes, causing about US$500 to US$700 million in damages. Such disruptions are increasing and creating ripple effects across global supply chains, driving price volatility and economic instability. Hence, investing in climate resilience, therefore, is not just a moral imperative for the Global North but also an economic necessity.

Governments and international institutions must work collaboratively with the private sector to address these challenges through blended finance solutions, which help de-risk investments and enhance returns.

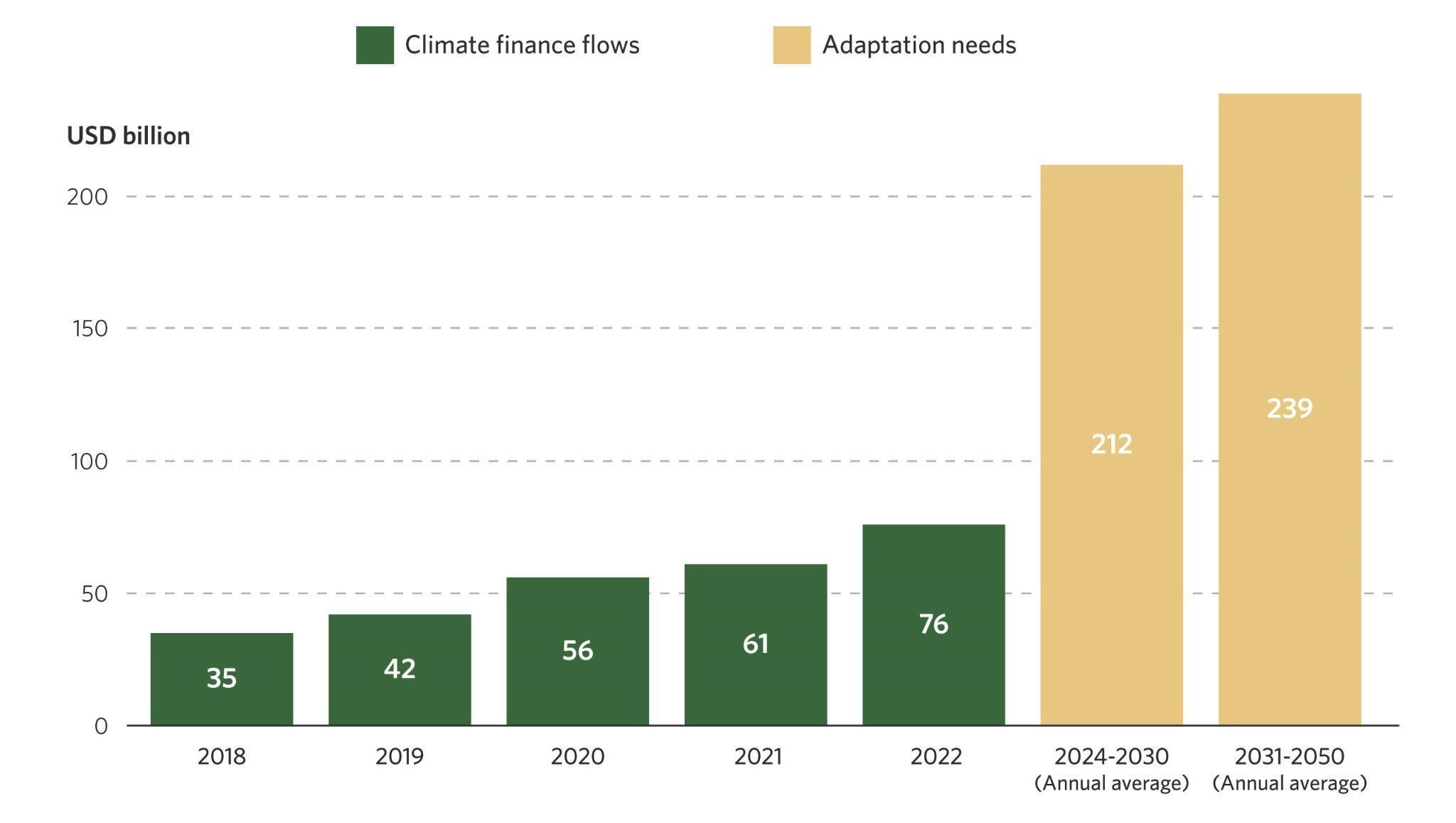

Second, private finance should also be leveraged. In 2023, private investment accounted for 49 percent of total climate finance and is expected to grow further. With over US$210 trillion in assets under management—institutional investors, pension funds, and multinational corporations have the potential to drive climate innovation and market creation. Mobilising these funds toward green infrastructure, renewable energy and climate resilience projects is critical. Companies are increasingly recognising the financial and reputational risks of inaction, fuelling a surge in sustainable investments. The rise of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) frameworks has propelled green financing to record levels, with global sustainable investments surpassing US$35 trillion in 2023. However, significant barriers persist, including perceived risks, policy uncertainties, and a lack of bankable projects in developing economies. Governments and international institutions must work collaboratively with the private sector to address these challenges through blended finance solutions, which help de-risk investments and enhance returns. Despite progress, private finance remains heavily skewed towards mitigation, while adaptation receives only 1.6 percent of total private climate finance. This imbalance must be corrected to ensure comprehensive climate resilience. Strengthening project pipelines, improving regulatory certainty, and expanding risk-sharing mechanisms will be key to unlocking private capital for both mitigation and adaptation efforts.

Figure 2: Global climate adaptation flows and needs

Source: CPI, 2024

Lastly, philanthropy represents a largely untapped opportunity to scale climate finance. In 2023, philanthropic funding for climate initiatives grew by 20 percent, reaching a record US $4.8 billion, but it still constitutes less than 2 percent of total philanthropic giving globally. The majority of philanthropic ventures continue to prioritise sectors like poverty alleviation and health, often overlooking the fact that climate change intersects with all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To address this, philanthropic actors must recognise the urgency of integrating climate action into broader development strategies, pooling resources into climate-focused initiatives for a more intersectional and holistic approach. The urgency of this shift is becoming undeniable. As the US steps back from its climate commitments, Michael Bloomberg has stepped in to maintain US contributions to the Paris Agreement. In the Global South as well, initiatives like the Indian Climate Collaborative are also mobilising local resources to bridge funding gaps. Philanthropy’s capacity to absorb risk and prioritise social impact over financial returns makes it an ideal vehicle to back high-risk adaptation projects in vulnerable regions. Governments can amplify these efforts by providing tax incentives, streamlining regulatory processes, and expanding blended finance models that leverage philanthropic capital to unlock additional investment.

The majority of philanthropic ventures continue to prioritise sectors like poverty alleviation and health, often overlooking the fact that climate change intersects with all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The US withdrawal, whether a disruption or an opportunity, should serve as a wake-up call to confront the deep inefficiencies in climate finance. The way forward lies in leveraging the complementary strengths of public, private, and philanthropic finance to build a resilient and inclusive climate finance ecosystem. Public finance must provide foundational equity, ensuring that systemic vulnerabilities are addressed. Private capital, with its vast resources, should be directed through policy incentives to support scalable, impact-driven projects. Meanwhile, philanthropy can de-risk high-risk adaptation efforts, acting as a catalyst for further investments. The urgency of the crisis demands strategic action from all sectors, creating an inclusive, just, and effective climate finance system—one that moves past rhetoric and finally delivers on its promises.

Sharon Sarah Thawaney is the Executive Assistant to the Director at the Observer Research Foundation, Kolkata

Aparna Roy is a Fellow and Lead for Climate Change and Energy with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Sharon Sarah Thawaney is the Executive Assistant to the Director - ORF Kolkata and CNED, Dr. Nilanjan Ghosh. She holds a Master of Social Work ...

Read More +

Aparna Roy is a Fellow and Lead Climate Change and Energy at the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy (CNED). Aparna's primary research focus is on ...

Read More +