Workforce implications of rising automation are profound; workers across industries are seeing its effects creeping into their offices in real time. The limitations of reskilling are just as complex as the difficult task of finding new jobs and then hanging in there. For migrant workers in foreign lands, there are added pressures of dealing with erratic political shifts. Those who work jobs that involve close human connect feel more insulated in the thick of the current zeitgeist. We bring you insights from the field, based on conversations with up-skillers and seek to understand their inputs based on layers of research from the world’s leading voices on technology’s ascent.

When Amresh Dubey’s phone rings any time of day or night, he doesn’t have the luxury of ignoring it. Bleary eyed yet always on alert, Dubey rarely gets enough shut-eye because he has “ownership” of mission, critical for IT systems across geographically diverse teams; he says the mayhem of an always-on lifestyle is messing with his health but he’s learnt to live with it. Despite his messy work schedule, he managed to steal some crazy hours and arm himself with a shiny new agile certification last fall. He plans to get “at least two more certifications” in a year. “My role is a mix of technical, managerial and sales. It will be challenging to play it with any less experience,” shrugs this New Jersey resident.

Amresh Dubey rarely gets enough shut-eye because he has “ownership” of mission, critical for IT systems across geographically diverse teams.

Amresh Dubey rarely gets enough shut-eye because he has “ownership” of mission, critical for IT systems across geographically diverse teams.

Why Agile, we asked Amresh. He says he believes it’s going to be “de facto for the next decade or so, for new project execution.”

Fast learning and adaptation remain the only key skills in the IT industry, he says.

Meet Shiv. Last summer, he was eagerly waiting for his Tesla Model 3 delivery and was about to close on a $400,000 home when his company got bought over, he lost his job in the US, and he hurriedly moved to neighbouring Canada from New York — all in a matter of a few manic weeks which have given him “stress related stomach ulcers.” He has put off his home buy and is back to his books while he shoots off his resume to recruiters. “Once I’m back in a regular job, I won’t have this kind of time on my hands,” he explains. Shiv has enrolled in MIT’s short course on ‘Artificial Intelligence: Implications for Business Strategy.’ That’s a fairly general topic, unlike a specific computer language. How will it help Shiv? “It’s the language everyone’s speaking. I might as well learn the vocabulary,” says Shiv who tells us he’s opened a Twitter account only to follow machine learning specialists.

In Houston, Texas, Becka Miller, came off a 11 year break caring for her three children and dumped a humdrum school job “that didn’t pay enough” and trained herself as a Salesforce consultant.

“Tech skills? I had none!” — she said while dwelling on the many tangles of starting a new career from scratch. “I remember my head wanting to explode while my husband tried to explain the difference between leads, accounts, contacts, and opportunities,” she says of the early days.

From that sputtering start in 2015, she has earned at least 6 Salesforce certifications to her name and now trains rookies looking for a foothold in the automated CRM business. The certifications won’t stop, Miller plans to keep adding to her kitty.

Miller lives in middle America, Dubey and Shiv are on the US East Coast; they are neither millennials nor are they baby boomers, they fall somewhere in-between — a cohort that occupies a unique niche in the generational hierarchy of the modern workplace.

These folks have witnessed the rise of the internet after having lived out their school and college years without mobile phones for most part and then gone on to make a living on the strength of digital transformation powering their personal and professional lives.

Incidentally, the average age for successful entrepreneurs (too) is between 42 and 47, no less. Harvard Business Review says evidence points to entrepreneurial performance “cresting” in the late fifties.

“If you were faced with two entrepreneurs and knew nothing about them besides their age, you would do better, on average, betting on the older one,” write Pierre Azoulay, Benjamin Jones, J. Daniel Kim and Javier Miranda.

Although none of the people interviewed for this article are ‘entrepreneurs’ in a way that it is commonly accepted, research suggests that the so-called ‘older worker’ is adept at adapting to new tools, environments or working practices.

‘Transportable’ skills which can be learnt in short bursts and applicable across a variety of industries are enjoying a surge of interest among mid career professionals keen to break out of a job funk.

“It’s not very different from modern day political theater. There’s so much talk about ‘younger’ voters tipping the balance it but it was us — the greying crowd — that swung it, both in Brexit and in the 2018 US midterms. I see similar forces are at work in the job market,” smiles Greg, a lymphoma survivor currently in training to be a physical therapist.

“Tech skills? I had none!” — Becka Miller said while dwelling on the many tangles of starting a new career from scratch.

“Tech skills? I had none!” — Becka Miller said while dwelling on the many tangles of starting a new career from scratch.

Multiple studies have come to the happy conclusion that upgrading skills makes workers more productive, raises individual incomes and also adds to country GDP. At a more intimate level, higher levels of education allow workers to adjust better to different demands of the workplace and help their earnings diverge from those of less educated.

Hanushek, Schwerdt, Wiederhold et al have found that adjustment to change has led to continual calls for enhancing lifelong learning, “particularly by those in jobs subject to more intense competition and by those currently receiving less continual training and upgrading.”

Also, the rising level of automation across industries is lending sharper focus to how workers think about investing in incremental skills.

The threat for middle and low skill workers is leading both employees and employers to think along the same lines of upskilling and reskilling.

“Whatever industry you work in, AI will transform it, just like electricity did when it came on the scene. AI is going to create new winners and losers based on the first step that’s already been taken — digital transformation — which allows AI to come in, eat that data and automate decisions,” Andrew Ng, Stanford adjunct professor and former Baidu scientist, said at a Wall Street Journal conference this October.

Ng lists online advertising is the single most lucrative area for application of AI tools; healthcare comes a far second.

Workers see the writing on the wall. According to an Accenture survey ‘Advancing missing middle skills for human AI collaboration,’ 67% of workers believe they must develop their skills to work with intelligent machines.

The same survey says “leaders should shift from ‘planning the workforce’ to ‘planning the work’” based on mapping internal capabilities to new roles and then develop new skills to bridge talent gaps.

“I’m not a techie but I oversee an offshore team of 100 people who are extremely good with hard core tech. I need to be able to speak the same language with some depth. That’s what I’m training for,” says Nalini Kumar, project manager at a listed bank.

Workers like Kumar believe their companies should do more to help. They cite lack of time (48 per cent), lack of sponsorship (37 per cent) and lack of resources (36 per cent) as the biggest barriers to developing new skills, in the same Accenture study.

But it’s not just skills that need polish, the old idea of job stability is changing fast too. “It’s no longer about being in the same place, it’s about being in the same job even if you get packed off to the wild west,” says Anne, who has been given a week to decide whether she is ready to move base from New York to Kansas.

For migrant workers, being able to live with erratic immigration policy is also a thing. Take for instance, the the US Department of Homeland Security’s proposed rule that came out on 30 November 2018 which plans to favour US master’s degree applicants over all other candidates for the H1B visa. “Even without this rule, we are having serious staffing issues,” says a techie from a large Indian outsourcing firm working with Credit Suisse. We have a requirement, we need a person in 10 days or a month, this H1B system is simply not working for anybody anymore. And, we are unable to find replacements. It’s a mess.”

In the US, tax cuts, job cuts and nearshoring are becoming the path to higher profits and workers have to adapt to more than just automation. “Most of my team is moving to Florida. Those who can’t move are out of contention,” says a Citigroup staffer in New York as the bank is slashing real estate costs in costly metros and moving to low tax, low rent, lower salary destinations within the US.

Erik Brynjolfsson frames the challenges of the current automation zeitgeist in a more useful way: Managers who embrace machine learning will replace managers who don’t, he told us in an interview earlier this year. Brynjolfsson and Tom Mitchell have come up with a 21 question rubric that helps almost anybody work through which tasks are the most suitable for machine learning. Understanding this framework helps both employers and employees refine thinking on where to spend money on reskilling.

And, because algorithms can be shipped instantly around the world, the sense of urgency more palpable among mid level employees, is palpable.

In short, AI algorithms will be to many white collar workers what tractors were to farmhands — a tool that dramatically increases the productivity of each worker and thus shrinks the total number of employees required, writes Kai Fu Lee in AI Superpowers.

Lee calls retraining a “nice idea” which is “far from enough to solve the bigger problem that looms where workers may be changing jobs every few years and rapidly trying to acquire skills that that took others an entire lifetime to build up.”

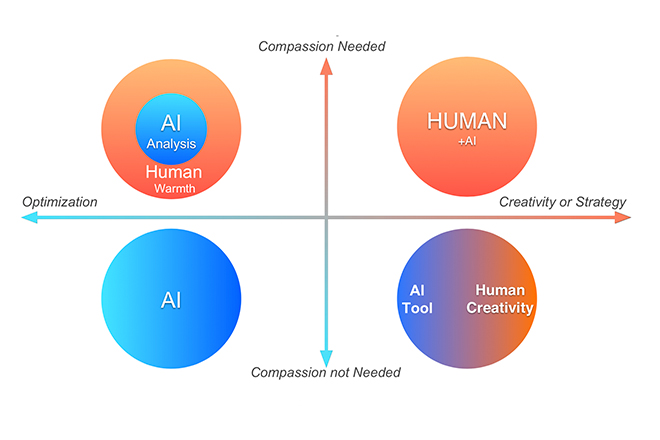

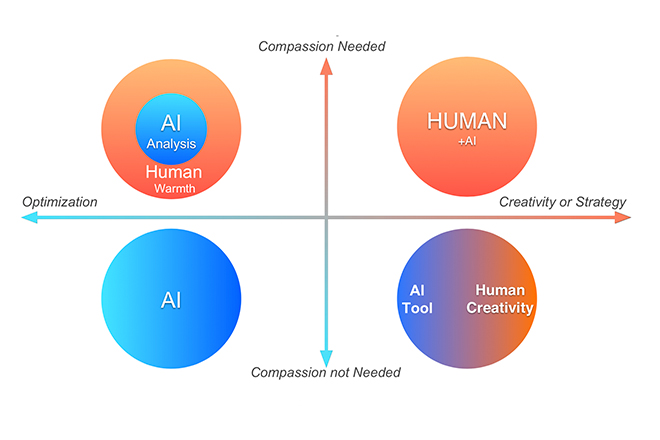

In the diagram alongside, Lee says retraining can particularly help folks in the bottom right quadrant — the ‘slow creep’ zone. Here, learning new tricks can help workers stay ahead of AI’s ability to think creatively or work in unstructured environments.

Learning new tricks can help workers stay ahead of AI’s ability to think creatively.

Learning new tricks can help workers stay ahead of AI’s ability to think creatively.

The CIO of a top US bank (who requested the bank not be named) tells us how Lee’s thinking applies to his own bank’s performance. This CIO says his company’s revenue has climbed 5x by using machine learning systems to provide better recommendations and leads for wealth management staff. “Those managers who were more willing to learn performed better for us and the skeptics are still having issues of adapting to the new work environment. Eventually, they’ll fade out. I can see it coming,” the CIO told us.

This example is one where the bank was ready to train its staffers on using the machine learning system but such cases are few and far in between — where the employer takes the lead in retraining. Recently, though, major US tech companies such as Microsoft, Google, and Cisco joined a World Economic Forum (WEF) plan to train 20 million Southeast Asian workers in digital skills by 2020. The plans are part of the WEF’s Digital ASEAN initiative.

But what about the rest?

Can we really expect a typical worker choosing a retraining programme to accurately predict which jobs will be safe a few years from now, asks Lee.

He responds with an equally chilling answer: “I fear workers will find themselves in a state of constant retreat like animals fleeing relentlessly rising floodwaters, anxiously hopping from one rock to another in search of higher ground.”

“A key lesson is that companies can’t expect to benefit from human-machine collaborations without first laying the proper groundwork. Again, those companies that are using machines merely to replace humans will eventually stall, whereas those that think of innovative ways for machines to augment humans will become the leaders of their industries,” write Paul H. Dauherty and H. James Wilson in Human + AI .

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that home health aides and personal care aides are the two fastest growing professions in the the country, with an expected growth of 1.2 million jobs by 2026.

For workers the world over, scrambling to the two upper quadrants in Kai Fu Lee’s graph hold the promise of insulation because of the higher dependence on what Lee calls “human veneer”: Doctors, wedding planners, teachers, tour guides, financial planners, remote tutors, bartenders, caterers, luxury hotel receptionists and cafe waiters make the cut.

Greg, mentioned earlier, who divides his time as a swim instructor and physical therapist, believes he’s landed in a sweet spot that’s “entirely unintended.” Greg took a break from college when he was diagnosed with lymphoma. By the time he was well, all his peers had passed out of school and already into jobs. “Both my jobs are completely about people and have almost nothing to do with machines, each person lands up with a fairly unique set of issues and I’ve begun to realise how valuable this is for me as a 32 year old in 2018.”

And the grim news? Radiologists, for instance, are in the crosshairs. If not now, then within five years for certain, says Ng.

“If any of you have friends or children or whatever studying Med school and graduating with a degree in radiology, I think they may have a perfectly fine 5 year career…the broader pattern is that in any job where there are many people doing relatively routine, repetitive tasks, that creates a big incentive for AI people to come in and automate.

“There’s one highly imperfect rule of thumb which I’ve often offered my teams which is that any task that a human can do in less than 1 second, we can automate using AI.”

Conclusion

There is often no single right answer to the question of what is the best reskilling or upskilling strategy. What, for instance, does the radiologist in Ng’s example (above) do five years down the line? What must this person train for today so that he/she remains gainfully employed when there’s a bot reading MRI and CT scan results? Avi Goldfarb, Joshua Gans and Ajay Agrawal provide lane markers in their recent book Prediction Machines: “So long as humans are needed to weigh outcomes and impose judgment, they have a key role to play as prediction machines improve.” Most research suggests that tasks most likely to be fully automated first are the ones for which full automation delivers the highest returns to the firm while better prediction raises the demand for human judgment. But once that entire process is set in motion, AI scales at much higher speed than humans, raising the stakes and the risks for all workers who roam the corridors outside the C-Suite.

The limitations of reskilling are just as complex as the difficult task of finding new jobs and then hanging in there. Without exception, all the reskillers who inform this article are bridging the present and future, they didn’t come armed from college with most of the tools they are learning or need. Compared with career relaunchers, those already holding down a job have an edge in figuring out what to learn anew based on their more intimate and daily brush with real time organisational processes. When America’s largest automaker General Motors laid off 15,000 workers recently, a much touted apprenticeship programme driven by the US president’s daughter has been of little use for those let go. Trump made things worse by lashing out at GM’s management for messing with his political rhetoric. For those out of work for even a few weeks, months or years, choosing a retraining program is both hard and expensive; it’s also fraught with the risk that what you’re learning may flame out by the time you find work. In Dying for a Paycheck, Jeffrey Pfeffer, a professor of organisational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business, cobbles numerous examples from all over the world to lay bare infuriating truths about modern work life. ‘Only Chumps Work More Than 40 Hours a Week’ reads a wildly popular headline on Medium, but if you’re working, upskilling and dealing with routine family stuff, you’re looking at 80-100 hour weeks in any case. Pfeffer’s book tells how the lion’s share of management practices are hurting employees and making them sick and not even leading to better profitability. In this piece, we haven’t plunged deep into how reskillers grapple with work-family issues, physical rest, downtime etc. Skivving at work and losing sleep is something many reskillers are forced to do no matter how bad they feel about slacking off. For some, that option doesn’t even exist. Rey, a young mom who waits tables in a New Jersey suburb says her legs “ache like hell” in the evenings but she is pushing ahead with night classes at the local community college while her husband stays home with the kids. “One of these nights, I fear I'm going to fall asleep at the wheel.”

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Amresh Dubey rarely gets enough shut-eye because he has “ownership” of mission, critical for IT systems across geographically diverse teams.

Amresh Dubey rarely gets enough shut-eye because he has “ownership” of mission, critical for IT systems across geographically diverse teams. “Tech skills? I had none!” — Becka Miller said while dwelling on the many tangles of starting a new career from scratch.

“Tech skills? I had none!” — Becka Miller said while dwelling on the many tangles of starting a new career from scratch. Learning new tricks can help workers stay ahead of AI’s ability to think creatively.

Learning new tricks can help workers stay ahead of AI’s ability to think creatively. PREV

PREV