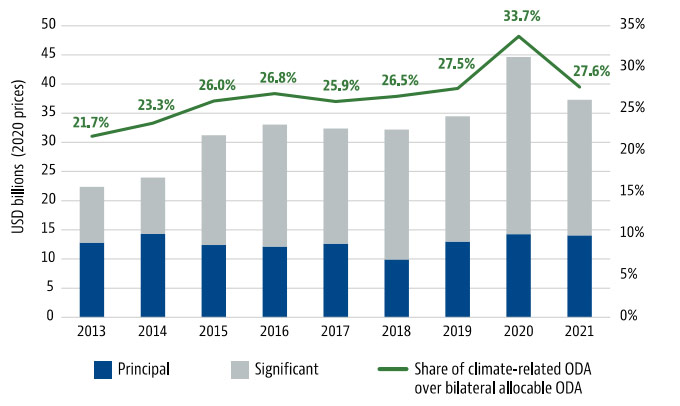

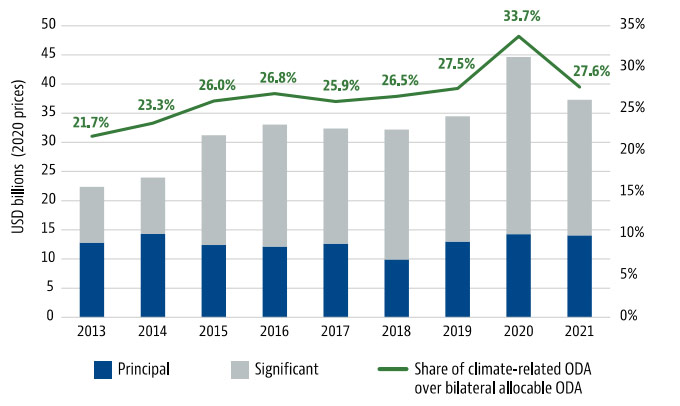

Reflecting a fiscal hangover following the pandemic, the world economy has somewhat proved its mettle by being resilient to inflationary attacks. As per the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2024 is likely to witness a mild slowdown of GDP growth at 2.7 percent compared to last year’s figure of 2.9 percent. However, with increasing calls for closer cooperation toward bridging the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) financing gap, the international development landscape paints a grim picture. It remains fragmented, fragile, and fractured. Magnified by the visible consequences of climate change along with increasing conflicts, renewed instabilities, and a decelerated economic outlook, there is a strong need for development providers to rethink their Official Development Assistance (ODA) strategies. While commitments from several of the Global North development providers for climate change have increased, climate finance is still falling short of what is needed. Despite the total amount of ODA touching an all-time high of US$ 204 billion in 2022, it fell short of meeting the annual needs of US$ 2,000 billion for realising the SDGs. According to OECD figures released in 2023, almost 27.6 percent of the allocable bilateral ODA in 2021 focused on climate action marking a slight drop from 33.7 percent in 2020 (Figure 1). A close look at these figures also reveals that although a major chunk of the ODA did target climate action (both mitigation and adaptation), it was not the fundamental driver for these allocations. In 2021, almost US$ 14 billion carried climate as a principal objective compared to US$ 23 billion with initiatives having climate as a significant objective.

Figure 1: Snapshot of bilateral climate-related ODA (2013-2021)

Source: OECD

Moreover, since the adoption of Agenda 2030, though climate-related development finance by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members of the OECD surged by almost 65 percent, a lower share was meted out to the ones who need it the most—environmentally vulnerable countries. As reported by the Centre for Global Development, out of the US$50 billion that donors gathered as part of the various climate funds, such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF), Global Environment Facility (GEF), and the Climate Investment Funds (CIF) under the World Bank banner, only 5.37 percent of this has been directed to the 10 most climate vulnerable economies. This reflects a ‘labyrinth of incongruent climate financing mechanisms’ completely alien for the low-income and vulnerable regions to fathom. Additionally, a visible divide is noticed when it comes to allocating ODA for climate adaptation vis-à-vis mitigation owing to several lacunae—a) lack of risk apportion and estimation; b) lack of incentives, particularly for the private sector for financing adaptation; c) lack of local capacity to absorb and employ funding, etc.

Countries in need should be in a position to secure not just adequate quantities of finance but also the requisite quality of finance—finance that creates sustainability.

Moreover, not only climate finance but the topic of humanitarian aid has also been occupying the conversation on financing in 2023. As per the Global Humanitarian Overview 2024 report released by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), the funding requirement for the humanitarian crisis is estimated to be approximately US$ 46.4 billion this year. Furthermore, in 2023, donors could only meet 35 percent of the total funding need of the UN, i.e., US$ 19.9 billion out of the US$ 56.7 billion. Of course, the unprecedented rise in unrest across the globe—Ukraine, Israel and Gaza, Sudan, and Afghanistan—has naturally put pressure on the development providers. In terms of numbers, ODA did rise dramatically but it has failed to keep pace with the rising need. Is ODA inept in dealing with the global impediments? Is there a need to refashion ODA or maybe think beyond ODA? The answer possibly lies in upholding the practice of ‘just financing’, as stated by Egypt’s Minister of International Cooperation, Rania Al-Mashat. Countries in need should be in a position to secure not just adequate quantities of finance but also the requisite quality of finance—finance that creates sustainability. Perhaps, encouraging cooperation among competing development providers can possibly provide positive pathways in an increasingly fragmented world. Furthermore, experts suggest ‘coopetition’ i.e., competing development providers working together to achieve similar objectives can potentially facilitate the distribution of benefits leading to innovative financing models, lower prices, and improved public goods. According to official figures, it is reckoned that global private investors have over US$410 trillion in financial assets, out of which US$2.5 trillion is spread across low- and middle-income countries. Experts suggest that these private pools of capital are one of the underutilised resources globally. In this context, the option of blended finance—combining concessional public funds with philanthropic capital to involve and attract the private sector—can also be effectively explored. However, inclusive development does not come by easily. Of course, one needs to put this into the perspective of the Global South countries which have been consistently wary of co-opting with their peers from the Global North owing to colonisation of ‘aid’ and practices of the ‘aid’ industry. Though there does not exist an exhaustive list of measures for ensuring just financing, experts believe that redesigning ODA must focus on three primary elements—a) reaching out to the vulnerable geographies by going beyond the North-South divide; b) devising new principles by incorporating values of mutual interest, solidarity with responsibilities, and burden-sharing; c) bringing new voices, actors, and agencies to fill the finance gap to build new coalitions. In this sense, 2024 could possibly turn out to be a pivotal year for development finance. It would be interesting to see how countries look to operationalise and reconcile their ODA allocations alongside climate exigencies.

Swati Prabhu is an Associate Fellow with the Centre for New Economic Diplomacy (CNED) at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV