This article is part of the Global Policy-ORF publication — A 2030 Vision for India’s Economic Diplomacy.

International mobility is an essential aspect of the development process, especially for India, which possesses a large demographic dividend as a distinguishing asset<1>. Therefore, global labour mobility is a key priority for the country’s economic diplomacy, and India has been an old and vocal proponent for the cause. The nature of work and labour force requirements worldwide have transformed over the past decade, catalysed further by the COVID-19 pandemic-induced digital acceleration. India’s old playbook of economic diplomacy may no longer suit this new and rapidly evolving landscape. India must therefore be cognisant of emerging debates around the future of work and geo-economic trends, to successfully advocate for international labour mobility and prepare its workforce per changing labour force requirements.

Economist Jagdish Bhagwati predicted that global labour mobility would be the engine of twenty-first-century growth, just as the movement of goods drove economic growth in the nineteenth century and that of capital dominated twentieth-century development<2>. The movement of people across borders is such a potentially powerful engine for development, that were it to be liberalised further, developing country incomes would quadruple and global GDP would double<3>. However, the political contestation around international migration has hampered its potential, earning it the epithet of “the last bastion of protectionism”<4>.

The movement of people across borders is such a potentially powerful engine for development, that were it to be liberalised further, developing country incomes would quadruple and global GDP would double.

This is especially so for unskilled labour migration — relatively speaking, developed countries tend to welcome skilled migrants (albeit, to an extent) but consider unskilled workers an economic, security and cultural threat<5>. This has unfortunately tempered the “irresistible forces” propelling migration, primarily that ageing prosperous economies require labour and poor demographically-endowed countries need to export surplus labour<6>. India is at the centre of this debate — it is among the world’s top origin-countries for migrants, with its international migrants more than doubling over the past 25 years<7>. It is also one of the top destinations for international migrants — in 2015, India hosted the 12th largest immigrant population globally<8>.

Migration is now recognised as a key function of sovereign diplomacy, going beyond traditional statecraft to ensuring well-governed labour migration, and the training and welfare of migrant workers<9>. But global labour mobility today is no longer restricted to the physical migration of labour. The forces of globalisation, coupled with technological shifts, are transforming work and production structures. The dematerialisation of the world economy has contributed to the rise of “virtual migration,” a flexible, disembodied labour supply across borders — a form of “migration without migrating” — that is coming to define the new labour economy<10>. In his book Virtual Migration: The Programming of Globalisation, A. Aneesh draws a distinction between “body-shopping” (hiring skilled workers who work for corporations overseas through sub-contracting practices) and “online programming” (skilled workers living in their home countries and working through the internet for corporations). The latter has received a fillip due to accelerating digital transformation and the shift to remote-first modes of working, engendered by the COVID-19 pandemic. With a large chunk of its workforce part of this ecosystem, India is the world's largest digital labour supplier<11>. This phenomenon therefore deserves a place in India’s imagination of its economic diplomacy for the future.

The dematerialisation of the world economy has contributed to the rise of “virtual migration,” a flexible, disembodied labour supply across borders — a form of “migration without migrating” — that is coming to define the new labour economy.

Shifting landscapes

The international mobility landscape is in a state of flux at present, precipitated by accelerating digital transformation and the changing contours of work, and made urgent by the COVID-19 pandemic’s tumultuous impact. This section is an exploration of evolving labour market trends that are expected to have an impact on Indian economic diplomacy’s agenda for promoting global labour mobility.

The COVID-19 pandemic

It would be remiss to discuss global trends affecting international labour mobility without mentioning the COVID-19 pandemic — historically, one of the biggest shocks to global migration<12>. The pandemic has prompted protectionist restrictions against the movement of people globally. Remittance flows globally declined by 6 percent year-on-year in Q2 of FY2020<13>, and are likely to fall even more sharply — the World Bank has predicted a 13 percent decline in global flows in 2020<14>, and a 23 percent decline in remittance flows to India<15>.

The pandemic’s impact on the labour market has been heterogeneous. Research suggests that migrant workers form a critical chunk of ‘essential services,’ such as healthcare and care work, that have been instrumental in fighting the pandemic across the world<16>. In some countries like the UK and Germany, migrants have earned considerable public favour by holding up their economies as ‘essential workers’ (Germany chartered flights to bring in agricultural labour). However, others, such as the US and the Gulf (two key destinations for Indian emigrants in particular), have put up protectionist barriers that are unlikely to be relaxed in the near term<17>.

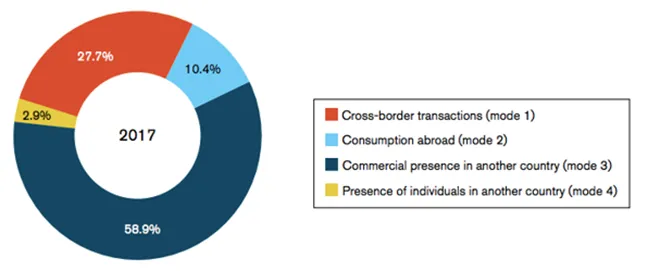

The pandemic will also likely magnify existing issues that had begun plaguing the migration economy, such as growing xenophobia and protectionism. A surge of xenophobia is already being seen in the Gulf countries, where the spread of the virus is being attributed to unskilled migrant workers and employers are being warned not to hire expatriate workers<18>. Protectionism is also likely to rise in this context; services under mode 4 — the presence or movement of natural persons — have always been the least liberalised of all modes of labour supply (see Figure 1). The pandemic is likely to reverse some of the meagre progress made in this regard<19>. As a service-led economy, India has long had labour mobility at the top of its trade negotiations agenda. However, there has been little appetite for mode 4 liberalisation in global trade deliberations, much to its discontent. The multilateral Trade in Services Agreement, launched in 2013 for this purpose and to which India was not a party, has also stalled<20>. India’s service exports continue mainly via mode 1 (cross-border supply)<21>.

The pandemic will likely magnify existing issues that had begun plaguing the migration economy, such as growing xenophobia and protectionism.

Figure 1: World Trade in Commercial Services by Mode of Supply, 2017

Source: World Trade Report 2019: The future of services trade<22>

Source: World Trade Report 2019: The future of services trade<22>

Restructuring labour markets and changing labour force requirements

The forces set into motion by the pandemic will likely cause a restructuring of labour markets. For one, the bulk outflow of migrants driven by the pandemic is unlikely to be reversed in equal proportions. Second, the threat of the transmission of infection may keep country borders closed for immigration for a considerable period, especially in developed states where vaccination will arrive first. Third, the recessions and employment crises witnessed across the world will also pressurise countries to put their citizens first, thereby hurting the cause of migration and development. Lastly, technological shifts will increase the demand for high-skilled workers more generally across the board.

The pandemic’s impact on the labour market will be heterogeneous, and it is critical to gauge where opportunities and challenges lie. The Gulf and the US have traditionally been the major destinations for Indian emigrant workers. In its May 2020 report, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimated that six million jobs will be lost in the Arab region due to COVID-19 and the oil shock<23>. The crisis is also likely to intensify the Gulf Cooperation Council’s ‘nationalisation policies,’ instated to create jobs for locals and reduce dependence on international migration<24>. Bahrain has already announced that jobs left vacant by migrants during the pandemic are to be filled by locals<25>. However, nationalisation policies are unlikely to have an extreme impact on the need for migrant workers in the short term<26>; for now, demand for migrants is expected to persist in the construction, care and hospitality sectors<27>. The region is looking to expand its tertiary-educated talent pool by 50 percent by 2030<28>, and in the longer term, labour requirements in the Gulf are expected to gradually move towards a smaller number of migrants with superior skills. Digital transformation coupled with the climate crisis is also likely to create demand in new sectors — for instance, the energy efficiency sector is expected to be the single largest generator of new employment in the UAE and is estimated to create more than 65,000 jobs by 2030<29>.

Nationalisation policies are unlikely to have an extreme impact on the need for migrant workers in the short term; for now, demand for migrants is expected to persist in the construction, care and hospitality sectors.

US-India relations mostly flourished under former US President Donald Trump, except on the issue of immigration. His temporary ban on several work visa categories hurt Indian H1B-visa workers disproportionately, and stringent conditions for the H1B visas, such as prohibitively high application fees, led India to file a case against the US at the World Trade Organisation (WTO)<30>. The restrictions are expected to be relaxed under US President Joe Biden. Biden’s campaign promises indicate that he will work to eliminate country-based quotas for high-skilled visas and exempt overseas PhD holders in science, technology, engineering and mathematics from visa caps, which is good news for India. Worryingly, however, Biden has remained conspicuously silent on the subject of the WTO and US tariffs<31>.

In addition to keeping an eye on trends in the above regions, the Indian government must also turn its attention to other key geographies that have considerable potential in this regard. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries are estimated to need 400 million additional workers by 2050 to hold up their social security systems<32>. The UK has recently indicated that it will be open to an “unlimited number of highly-skilled Indian workers” from 2021 onwards<33>. Promisingly, the European Union (EU) is also assessing the prospect of liberalisation of both skilled and unskilled migration. An ILO report suggested that there are higher shortages in the skilled sector in Europe — medicine and engineering being two key areas — even as requirements differ by country and must be assessed accordingly. The mobility of science and technology professionals could, therefore, be a key area for India-EU negotiations<34>. The EU has acknowledged the pressing need for labour — and the failure of migration regimes thus far — to put in a framework for the recruitment of low-skilled workers in a way that reduces irregular and illegal migration<35>. The Indian government must note this development, and reinvigorate efforts to work with the EU to a constructive dialogue in this area. The India-EU Declaration of Common Agenda on Migration and Mobility (2016) is a commendable step towards this goal. Future initiatives must focus on key areas of interest like student mobility and the governance and prevention of irregular migration (especially from North India to the EU, which will require the cooperation of the relevant Indian states)<36>. Additionally, Japan has recently begun liberalising its stance on immigration in recognition of the needs of its ageing population, and foreign workers in the country have doubled since 2013. Japan has fast-tracked permanent residency for skilled workers and, importantly, also passed a law to expand the quantum of blue-collar visas and provide blue-collar workers a path to permanent residency<37>.

The EU has acknowledged the pressing need for labour — and the failure of migration regimes thus far — to put in a framework for the recruitment of low-skilled workers in a way that reduces irregular and illegal migration.

There has also been some speculation recently that the shift to remote, virtual work during the pandemic may provide a fillip to “virtual migration” and the possibility for skilled workers to work across borders more fluently. However, at present, the ILO estimates that only about 18 percent of workers globally are in sectors that can work effectively from home, and have access to a conducive environment and infrastructure to do so. Therefore, this phenomenon may have a more muted impact on international labour mobility than expected<38>.

The future of work

What will the restructuring of labour markets due to emerging technologies likely look like? The deployment of emerging technologies is now causing a ‘hollowing out’ of the global workforce, with middle-skill jobs beginning to vanish. It has also created a ‘skill bias’ — high-skilled labour is in greater demand and has been more resilient and fared better during the pandemic<39>. White-collar non-routine occupations are also relatively more immune from automation, even though susceptibility to automation remains frustratingly difficult to predict and plan for<40>. In the long-term, this skill bias is expected to cause a large-scale shift in the structure of demand for labour at the expense of developing countries’ large pools of unskilled labour.

In their book Ghost Work, Mary Gary and Siddharth Suri have pointed to a more recent phenomenon that is emblematic of the effect of digital transformation on labour markets — the rise of a near-invisible global workforce that has emerged to power the platform economy<41>. The book refers to a virtual, high-skilled globally-distributed workforce that performs flexible, task-based work and reports to an application programming interface (API). India is at the core of this phenomenon, and is rapidly becoming the artificial intelligence (AI) backend office of the world<42>.

Gray and Suri estimate that by 2055, 60 percent of today’s global employment will have converted into ghost work<43>. This may well happen sooner; with regular jobs disappearing during the global pandemic-induced recession, their ranks have likely been vastly inflated. The size of this workforce is currently difficult to estimate, as the nature of their work is practically invisible. While this type of work has provided opportunities in the form of flexible ‘virtual migration’ and the ability to work for employers across the world, it has also extracted a high cost. Digital blue-collar workers face the problem of plenty — supply of workers vastly exceeds demand for their services — which has squeezed their wages and bargaining power, and led to a feeling of alienation and the loss of job security and mobility. Collective action is harder for them; as the nature of their work is disintermediated, they are dispersed all over the globe and view each other as competition<44>. The cross-border, invisible and informal nature of this work has created tremendous regulatory challenges. The role of the state must first extend to efforts towards making these labour supply chains visible, by defining platform work clearly and creating comprehensive databases for these workers. India’s Union Budget 2021 has taken a laudable step towards that end by provisioning for a minimum wage across all categories of workers, which will also be tremendously beneficial for these workers if implemented well. The role of economic diplomacy in this regard is crucial — regulation of ‘ghost work’ requires international collaboration and alignment of regulatory practices as workforces are dispersed all over the world.

Digital blue-collar workers face the problem of plenty — supply of workers vastly exceeds demand for their services — which has squeezed their wages and bargaining power, and led to a feeling of alienation and the loss of job security and mobility.

Recalibrate India’s economic diplomacy

In light of the changing global outlook, it is imperative for India to recalibrate its economic diplomacy framework, to enable its advocacy for global labour mobility in the future. This section shall proceed issue-wise and attempt to come up with a broad roadmap for this purpose.

A creative and pragmatic approach

India needs to rethink its approach towards engaging in debates on the future of global labour mobility. India has been disappointed time and again at the WTO — most recently in 2017, when it tabled its draft negotiating text called the Trade Facilitation Agreement for Services<45> — and regional fora such as at the recently concluded negotiations of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)<46>. India’s decreasing manufacturing competitiveness has led it to become increasingly defensive in trade negotiations with regard to market access in areas like agriculture, retail and dairy, making it difficult for the country to bargain for greater services liberalisation, as the RCEP negotiations demonstrated. In such a situation, it is patient and creative diplomacy, rather than an offensive stance, that may enable India’s cause.

One solution is to identify bilateral opportunities for partnership rather than multilateral engagement — an idea that has already yielded dividends for India. Among the key barriers for partnerships on global mobility are a lack of trust, concerns around the economic and security-related domestic impact of migration, and (now) health risks. Therefore, while negotiating, India will need to delve into several issues, such as those related to liability for overstay, illegal migration and the enforcement of temporary guest worker rules, and offer to assume some legal responsibility for monitoring and compliance as well<47>.

Among the key barriers for partnerships on global mobility are a lack of trust, concerns around the economic and security-related domestic impact of migration, and (now) health risks.

India also needs to think creatively to carve out greater policy space for itself in negotiations. One solution advanced by the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations is the introduction of start-up visas. This will serve to attract innovative talent to the country and also demonstrate India’s willingness to reciprocate on high-skilled labour mobility liberalisation, shifting the country’s policy stance to one more inclined to engage and compromise rather than just demand<48>. This would also enable India’s diaspora policy, and provide a route for inviting greater diaspora participation in domestic development. While focusing on bilateral engagement, India must continue to push on the multilateral front as well, and remain engaged with the WTO and forums like RCEP, with a view to build consensus on the growing need for well-designed labour mobility channels.

Invest in a capable workforce

A domestic as well as an emigration prerogative, India needs to invest in enhancing the capabilities of its workforce. Skills requirements are not a monolith, and neither is the future of work. Skilling programmes need to address the starting points of learning, for what is a highly segmented workforce.

A workforce of the future needs to be agile and move fluently between occupations. Basic digital fluency will be critical, even as a section of the population needs to be trained in higher-order technological skills. Skill-biased technological change will create greater demand in the areas of AI, machine learning, robotics, big data and natural language processing across the board. Soft skills, meanwhile, are often underemphasised but will be critical to every profession<49>.

Skills requirements are not a monolith, and neither is the future of work. Skilling programmes need to address the starting points of learning, for what is a highly segmented workforce.

India’s National Education Policy has encouragingly aligned vocational education and apprenticeships with formal educational attainments<50>. The government has done well to engage multiple agencies in migration governance for the purpose of capability-building — with the Ministry of Labour and Employment and Ministry of Skills Development and Entrepreneurship taking on key roles. However, the problem of skill mismatch remains high, as is the challenge of skill recognition across borders. Addressing this will require an integrated policy and certification framework, put into place collaboratively by sending and receiving countries<51>. It also requires efforts towards strengthening India’s Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL) programme as a priority — much of India’s workforce, contrary to popular perception, is already skilled but unrecognised and uncertified<52><53>. Technology-based solutions can also make intermediation more transparent — online job platforms, skills verification and tests and the verification of contracts will make job matching more efficient<54>.

Capability-building will require a tailored policy. For example, to promote semi-skilled and unskilled worker migration to the EU, India — with the support of EU policymakers — must create training and certification programmes oriented towards EU standards, targeted towards sectors like hospitality, healthcare, construction and care work, which are likely to see high demand<55>.

An updated diaspora policy

Academic and policy discussions have largely tended to focus on the impact of diaspora in their host countries, relatively few studies focus on the political and economic impact on the countries of origin, due to paucity of data. India must look at this phenomenon closely as well<56>. Unskilled migration usually has a net positive impact on the country of origin, however, skilled migration has both negative and positive effects.

The negative effect that India needs to pay particular attention to is brain-drain, which has arguably had a tangible impact on the quality of Indian universities. India has been a “net exporter of talent,”<57> which matters for economic diplomacy as well as development, as the country’s domestic fortunes are inextricably tied to its international exercise of influence. This problem requires serious consideration. Labour mobility agreements can be designed to promote this — we can move training to the country of origin and provision for a net ‘brain gain.’ The Australia Pacific Training Coalition (ATPC), a skilling drive to meet the region’s labour requirements, provides a case study for this<58>. The ATPC has a ‘home’ track and an ‘away’ track, and the ‘away’ track provides language, digital literacy, cultural training, RPL and other necessary work abroad training as well. Crucially, it also has a programme for investing in the return and reintegration of workers through ‘Full Circle Programmes,’ including a promising means to access platforms while away, to support their RPL applications, to know what kind of work is possible and available for returnees.

The negative effect that India needs to pay particular attention to is brain-drain, which has arguably had a tangible impact on the quality of Indian universities.

The attitude of the government towards domestic development and addressing push factors for emigrants often matters immensely for its success with diaspora engagement and reverse migration strategies<59>. Additionally, India also needs to find more creative and deeper-rooted ways of engaging its diaspora in development initiatives. A successful policy will recognise that the diaspora is not a homogeneous category and must be seen as distinct categories — such as differentiating between non-resident Indians, and ‘older’ migrants who migrated early as distinct from recent migrants. Diaspora policies must then be tailored according to their relevance for these different groups<60>.

A large chunk of the Indian diaspora is highly skilled and diaspora organisations can therefore act as effective mentoring networks and help complement skilling initiatives<61>. But to be effective, diaspora policy must be more welfare-oriented and empathetic in tone and content<62>. India needs a migration policy that extends to the treatment of overseas Indian workers. The pandemic has put a spotlight on the shabby, vulnerable living conditions of migrant populations in many parts of the world. This is a failure of the international migration governance framework and further evidence of the urgent need for national economic diplomacy to address this glaring vacuum in policy<63>.

An adaptive and empathetic policy framework

The rising complexity of economic diplomacy requires bureaucracies to design their frameworks to be more adaptive, reasonably decentralised and with strong inbuilt feedback mechanisms<64>. The necessity of feedback mechanisms is evidenced by India’s experience with migration governance in the Gulf. India-mandated minimum referral wages are facing implementation challenges, due to contract substitution in the destination country (contract substitution refers to an informal practice where foreign workers sign a contract before they migrate, but are compelled to accept a different, weaker contract on arrival in the destination country)<65>. Indian embassies could act as feedback nodes for policy in this regard. A plurilateral approach including all stakeholders, such as employer and employee organisations, and greater inter-ministerial coordination will promote more effective governance.<66> The need for domain expertise in India’s bureaucracy<67>, and better systems for retaining and creating institutional knowledge within ministries<68>, have often been brought up as areas of critical reform.

A plurilateral approach including all stakeholders, such as employer and employee organisations, and greater inter-ministerial coordination will promote more effective governance.

Adaptive policy could identify and plug the existence of policy vacuums that impede governance. One such vacuum is wage-theft, especially in the Gulf, where workers are denied their dues by companies in violation of their terms of contract. The e-Migrate platform instituted by the Indian government to coordinate across stakeholders has helped mitigate this problem and could be improved through integration with labour platforms in Gulf countries. Setting up mechanisms for Indian workers to air grievances could also help — the Indian repatriation form to be filled by migrants during COVID-19 did not provide any space for workers to discuss their grievances and seek redressal<69>.

Evidence-based adaptive policy also requires quality data. There is a need for more cross-country, comparative data sets and more data on migration flows and the enforcement of labour laws to realise the vision for a 2030-ready economic diplomacy framework for India.

There is an urgent need for Indian diplomacy to take a more welfare-oriented and rights-based approach towards emigration. India could begin by deliberating upon transitional justice mechanisms to address the immediate grievances and claims of repatriated workers due to the pandemic. India also needs to take this opportunity to push for broader reforms. The pandemic has prompted Qatar to dismantle the ‘Kafala’ system (a legal framework defining employer-employee relations, which has become increasingly exploitative)<70> and some other Gulf countries have expanded access to free healthcare and mandated private companies to provide accommodation to migrants. Governing return migration flows will now require coordination from both sending and receiving countries, and India must take this opportunity to co-build a welfare framework for migrant workers in cooperation with Gulf governments, for mutual benefit<71>.

The rights-based framework must also extend to immigrants received by India. Indian immigrants migrate irregularly and are often unrecorded, which is why there is a paucity of literature and lack of reliable figures on immigrant migration flows<72>. The conduct of India as a destination country is a critical component for economic diplomacy, even as it is beyond this paper’s scope.

The rights-based framework must also extend to immigrants received by India.

Upcoming emigrant bill

India’s draft emigrant bill, yet to be passed by parliament, will replace the Emigration Act of 1983 as the overarching and only legal instrument responsible for dealing with emigration and migrant welfare. However, the current draft bill excludes many, such as the families of emigrant workers and irregular and undocumented migrants. This will hurt India’s bilateral and multilateral efforts towards promoting labour mobility. The bill also neglects to focus on migrant rights in their destination country and the governance of return migration<73>.

In a bulletin released in 2007, the World Health Organisation stated that “international human mobility is factorial to the globalisation of infectious and chronic diseases” and that it poses a national security threat<74>. This is now evident. India’s draft emigrant bill makes no mention of mobility during crises and does not consider the importance of social security and health insurance for its migrants. The pandemic has demonstrated the urgency to work towards greater awareness and access to health and welfare services, and a transnational health framework that is inclusive of migrants. While including these provisions in its own legal framework, India must also work to include this request in its bilateral labour agreements<75>.

Conclusion

Global labour mobility is a critical instrument for promoting India’s development aims, and therefore features increasingly prominently in its economic diplomacy agenda as well. This paper has put forth two broad sets of arguments. One, it has elucidated the changing global outlook for labour mobility considering the pandemic and the evolving future of work. Two, it has provided a roadmap for India to recalibrate its economic diplomacy given this shifting outlook and has provided policy recommendations towards this end.

The subject of international labour mobility has often been averse to international cooperation, with origin and destination countries taking on adversarial stances, resulting in a fragmented and reactive approach to migration. However, a collaborative framework born out of pragmatism and an understanding of changing global trends and common challenges is both possible and desirable to leverage the gains from global labour mobility mutually<76>.

Endnotes

<1> “Global labour mobility is in India’s interest,” The Hindu, 7 May 2018.

<2> Basant Kumar Potnuru and Vishishta Sam, “India–EU engagement and international migration: Historical perspectives, future challenges, and policy imperatives,” IIMB Management Review, 27, no. 1 (March 2015), 35–43.

<3> “Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP): Helping Connect International Labor Markets,” Center for Global Development.

<4> Manjula Luthria, “Three Funerals and a Wedding: Resetting the way we work on migration,” World Bank Blogs, 12 September 2013.

<5> Lant Pritchett, Let Their People Come: Breaking the Gridlock on Global Labor Mobility (Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development, 2006).

<6> “Labor Mobility Partnerships (LaMP)”

<7> Phillip Connor, “India is a top source and destination for world’s migrants,” Pew Research Center, 3 March 2017.

<8> Connor, “India is a top source and destination for world’s migrants”

<9> Gerasimos Tsourapas and Fiona B. Adamson, “How countries use ‘migration diplomacy’ to pursue their own interests,” The Conversation, 4 February 2019.

<10> Rina Ghose, “Virtual Migration: The Programming of Globalization. A. Aneesh,” Urban Geography 28, no. 5 (2007): 511–12.

<11> Sangeet Jain, “Reimagining work and welfare for the Indian economy,” Observer Research Foundation, 27 October 2020.

<12> Delphine Strauss, “Pandemic ends a decade of growth in global migration,” Financial Times, 19 October 2020.

<13> Strauss, “Pandemic ends a decade of growth in global migration”

<14> “World Bank Predicts Sharpest Decline of Remittances in Recent History,” World Bank, 22 April 2020.

<15> “Remittances to India likely to decline by 23% in 2020 due to Covid-19: World Bank,” India Today, 23 April 2020.

<16> “Labour migration at the time of COVID-19,” International Training Centre of the International Labour Organization, 16 April 2020.

<17> Strauss, “Pandemic ends a decade of growth in global migration”

<18> Huda Alsahi, “COVID-19 and the Intensification of the GCC Workforce Nationalization Policies,” Arab Reform Initiative, 10 November 2020.

<19> Pralok Gupta, “There is no appetite in the world for Mode 4 commitments,” Trade Promotion Council of India, 18 July 2019.

<20> Linda Yueh, “Economic Diplomacy in the 21st Century: Principles and Challenges,” LSE IDEAS Blog, 27 August 2020.

<21> “Global services trade: What makes India different,” The Economic Times, 24 August 2019.

<22> World Trade Organization, World Trade Report 2019: The Future of Services Trade, World Trade Organization, 2019.

<23> Rejimon Kuttappan, “Indian migrant workers in Gulf countries are returning home without months of salary owed to them,” The Hindu, 19 September 2020.

<24> Alsahi, “COVID-19 and the Intensification of the GCC Workforce Nationalization Policies”

<25> Rhea Abraham, “Migration Governance in a Pandemic: What Can We Learn from India’s Treatment of Migrants in the Gulf?” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 55, Issue No. 32-33 (8 August 2020).

<26> Alsahi, “COVID-19 and the Intensification of the GCC Workforce Nationalization Policies”

<27> Froilan T. Malit, Jr and George Naufal, “Future of Work: Skills and Migration in the Middle East” (presentation, Inter-Regional Experts Forum on Skills and Migration in the South Asia-Middle East Corridor).

<28> “The Future of Jobs and Skills in the Middle East and North Africa: Preparing the Region for the Fourth Industrial Revolution,” World Economic Forum, May 2017.

<29> “The Future of Jobs and Skills in the Middle East and North Africa”

<30> Gupta, “There is no appetite in the world for Mode 4 commitments”

<31> Devirupa Mitra, “What a Biden Administration Could Do – Or Not Do – for India’s Key Priorities,” The Wire, 8 November 2020.

<32> Rebekah Smith and Cassandra Zimmer, “The COVID-19 Pandemic Will Probably Not Mark the End of the Kafala System in the Gulf,” Center for Global Development, 28 October 2020.

<33> “Britain has a good news for Indians who want to migrate to UK,” The Economic Times, 17 January 2019.

<34> Potnuru and Sam, “India–EU engagement and international migration”

<35> Stefano Bertozz ed., Opening Europe’s doors to unskilled and low-skilled workers: A practical handbook (Bureau of European Policy Advisors, 2010).

<36> Potnuru and Sam, “India–EU engagement and international migration”

<37> Noah Smith, “Japan Begins Experiment of Opening to Immigration,” Bloomberg Opinion, 23 May 2019.

<38> Janine Berg, Florence Bonnet and Sergei Soares, "Working from home: Estimating the worldwide potential,” VoxEU & CEPR, 11 May 2020.

<39> Sangeet Jain, “The coronavirus has hurtled unprepared economies into the future of work,” Observer Research Foundation, 29 April 2020.

<40> Daniel Susskind, A world without work: Technology, automation and how we should respond (UK: Penguin UK, 2020).

<41> Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri, Ghost work: How to stop Silicon Valley from building a new global underclass (Boston: Eamon Dolan Books, 2019).

<42> Abrieu Ramiro, Martin Rapetti, Urvashi Aneja and Krish Chetty, “How to Promote Worker Wellbeing in the Platform Economy in the Global South,” G20 Insights, 7 May 2019.

<43> Ann Toews, “‘Ghost Work' in Modi's India: Exploitation or Job Creation?” Foreign Policy Research Institute, 28 June 2019.

<44> Ramiro et al., “How to Promote Worker Wellbeing in the Platform Economy in the Global South”

<45> D. Ravi Kanth, “India sets the stage for a clash with US, EU at WTO,” The Mint, 1 March 2017.

<46> Surupa Gupta and Sumit Ganguly, "Why India Refused to Join the World’s Biggest Trading Bloc,” Foreign Policy, 23 November 2020.

<47> Pritam Banerjee, “Fixing India’s Economic Diplomacy,” The Diplomat, 16 June 2017.

<48> Arpita Mukherjee, Avantika Kapoor and Angana Parashar Sarma, “High-Skilled Labour Mobility in an Era of Protectionism: Foreign Startups and India,” ICRIER Working Paper, July 2018.

<49> Sangeet Jain, “The National Education Policy 2020: A policy for the times,” Observer Research Foundation, 6 August 2020.

<50> Ministry of Human Research Development, National Education Policy 2020.

<51> Panudda Boonpala and Max Tunon, “Quality Not Quantity – It’s Time To Re-Think Overseas Employment,” UN Blogs.

<52> Laura Sili, “Technology and the future of work in developing economies,” International Growth Centre, 20 March 2019.

<53> Yueh, “Economic Diplomacy in the 21st Century”

<54> Steffen Hertog, “The future of migrant work in the GCC: literature review and a research and policy agenda,” London School of Economics and Political Science (paper presented at Fifth Abu Dhabi Dialogue Ministerial Consultation of Abu Dhabi Dialogue Among the Asian Labor Sending and Receiving Countries, 16-17 October 2019).

<55> Potnuru and Sam, “India–EU engagement and international migration”

<56> Devesh Kapur, Diaspora Development and Democracy: The Domestic Impact of International Migration from India (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010).

<57> Devesh Kapur, “Migration and India,” Centre for the Advanced Study of India, 30 August 2010.

<58> Helen Dempster and Andie Fong Toy, “How Has COVID-19 Affected APTC’s Efforts to Promote Labor Mobility in the Pacific?” Centre for Global Development, 13 July 2020.

<59> Ashley J. Tellis, “Troubles Aplenty: Foreign Policy Challenges for the Next Indian Government,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 20 May 2019.

<60> Alwun Didar Singh, “Working with the Diaspora for Development Policy Perspectives from India,” CARIM-India Research Report 2012/25, Fiesole, European University Institute and Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, 2012.

<61> Mukherjee et al., “High-Skilled Labour Mobility in an Era of Protectionism”

<62> Parama Sinha Palit, “Modi and the Indian Diaspora,” RSIS Commentary, no. 241 (28 November 2019).

<63> Nithin Coca, “How can we better protect migrant workers in the next global crisis?” Devex, 24 September 2020.

<64> “Building bureaucracies that adapt to complexity” (webinar, Overseas Development Institute, 30 November 2020).

<65> Boonpala and Tunon, “Quality Not Quantity”

<66> “Global labour mobility is in India’s interest,” The Hindu, 7 May 2018.

<67> Arjun Bhargava, “Economic diplomacy is now core component of India’s foreign policy,” Observer Research Foundation.

<68> Banerjee, “Fixing India’s Economic Diplomacy”

<69> Kuttappan, “Indian migrant workers in Gulf countries are returning home without months of salary owed to them”

<70> Kali Robinson, “What Is the Kafala System?” Council on Foreign Relations, 20 November 2020.

<71> Smith and Zimmer, “The Covid-19 pandemic will probably not mark the end of the Kafala system in the Gulf”

<72> UNESCAP, In-migration: Situation Report, UNESCAP.

<73> S. Irudaya Rajan, Varun Aggarwal and Priyansha Singh, “Draft Emigration Bill 2019: The Missing Links,” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 54, Issue No. 30 (27 July 2019).

<74> Abraham, "Migration Governance in a Pandemic”

<75> Abraham, "Migration Governance in a Pandemic”

<76> Potnuru and Sam, “India–EU engagement and international migration”

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source: World Trade Report 2019: The future of services trade

Source: World Trade Report 2019: The future of services trade PREV

PREV