-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The Supreme Court’s recent 547-page verdict affirming the fundamental right to privacy of Indians should not come as news to technology companies. The court merely codifies what should have been an article of faith for internet platforms and businesses: the user’s space is private, into which companies, governments or non-state actors must first knock to enter.

The technical architecture of Aadhaar and its associated ecosystem too will now be tested before a legal standard determined by the court, but the government should see this judgment for what it is - a silver lining.

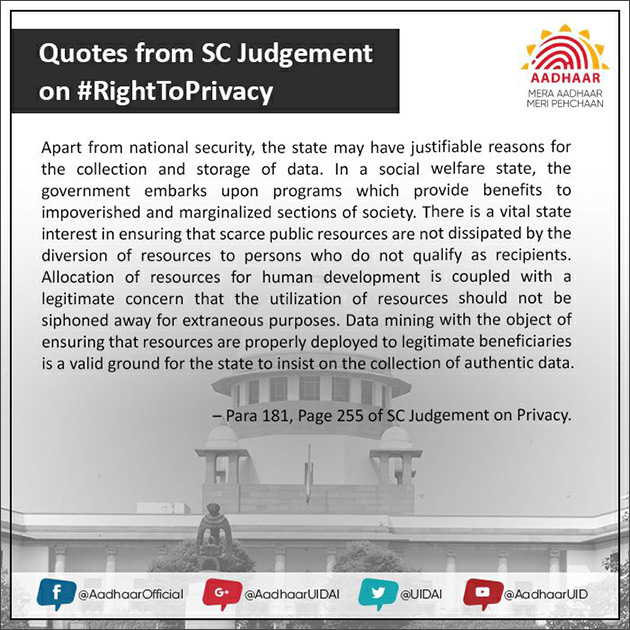

The verdict bears enough hints to suggest the Supreme Court sees the merits in a biometrics-driven authentication platform. In fact, Justice Chandrachud impresses upon the possibility of better governance through big data, highlighting that it could encourage ‘innovation and the spread of knowledge’, and prevent ‘the dissipation of social welfare benefits.’

The court’s words should spur the government to create a “privacy-compliant Aadhaar”, but this requires a serious and systematic thinking on the part of its visionaries and architects. Private sector too will have to put “data integrity” and privacy at the core of their consumer offerings and engagement.

To begin with, the government must account for Aadhaar’s biggest shortcomings — its centralised design and proliferating linkages.

A central data base creates a single, and often irreversible, point of failure. The government must decentralize the Aadhaar database. Second, Aadhaar must be a permission-based system with the freedom to opt-in or out, not just from the UID database but from the many services linked to it. This must be a transparent, accessible and user friendly process.

With a “privacy-compliant” Aadhaar, the government would not merely be adhering to the Supreme Court verdict. It would also be on the verge of offering the world’s most unique governance ecosystem, a feat that more technologically advanced nations such as America and China have failed to achieve.

Take Beijing’s efforts in this space, for instance. In 2015, the government of the People’s Republic of China unveiled a national project to digitize its large, manufacturing-intensive economy and to create a digital society. The “Internet plus” initiative, as it was called, aimed for the complete “informationisation” of social and economic activity, and harvest the data collected to better provide public and private services to citizens. China has no dearth of capital or ICT infrastructure, but the ‘Internet plus” initiative has struggled to take off in any significant way, nor has it found any international takers. The project suffered from a fundamental flaw: Beijing believed by gathering information — from personally identifiable data to more complex patterns of user behaviour — the state would emerge as the arbiter of future economic growth, consumption patterns and indeed, social or political agendas.

But trust in the digital ecosystem, as the failed Chinese government attempt at technology enabled social-engineering shows, can only be built by addressing those needs which extend to the demand for freer expression, political dialogue and economic mobility. On account of its closed governance model, Beijing has arguably failed to generate such trust among internet users. China’s failure to move forward on its grand digital project bears lessons for India.

If a project like Aadhaar is to succeed, its underlying philosophy must be premised on two goals: first, to increase trust and confidence in India’s digital economy among its booming constituency of internet users, and second, to ensure that innovations in digital platforms also result in increased access to economic and employment opportunities.

A privacy compliant Aadhaar creates trust between the individual and the state, allowing the government to redefine its approach to delivering public services. The Aadhaar interface, that UPI and other innovations rely on, could well generate a ‘polysemic’ model of social security, where the same suite of applications cater to multiple needs such as digital authentication, cashless transfers, financial inclusion through a Universal Basic Income, skills development and health insurance. But such governance models should not be based on a relationship of coercion or compulsion. It is heartening that the country’s political class has embraced the court verdict, with BJP’s leaders like Amit Shah affirming their commitment to create a “robust privacy architecture” and the Srikrishna Committee’s efforts to recommend one.

A key reform missing in current debates about the UID platform is the government’s accountability for its management. Aadhaar, to this end, should have a chief privacy officer — or indeed a “privacy ethicist” not unlike the major technology companies —who will be able to assess complaints, audit and investigate potential breaches of privacy with robust autonomy.

An Aadhaar based ecosystem which is both privacy-compliant and has built a bottom-of-the-pyramid financial architecture would inspire confidence in other emerging markets to also adopt the platform, with Indian assistance.

Companies and platforms must internalise that promise of black box commitments towards privacy and data-integrity may no longer suffice. These commitments must be articulated at the level of the board and communicated to each user that engages with them. Overseers of data integrity must be appointed to engage with users and regulators in major localities.

India’s digital growth story must be scripted by its people and for its people. The Indian state, however, has an important role to play here — it should catalyse technology platforms that provide reliable, affordable and qualitative internet access to citizens. But most importantly, the state should articulate a bold political, legal, and a philosophical narrative that can drive innovations, both by public and private organizations, in India and abroad. With a privacy compliant Aadhaar, this narrative could be one of empowerment, inclusivity and prosperity enabled by digital networks.

(A shorter version of this article was published in Economic Times)

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Samir Saran is the President of the Observer Research Foundation (ORF), India’s premier think tank, headquartered in New Delhi with affiliates in North America and ...

Read More +