The Foreign Trade Policy (FTP) 2021-26 was due to be released last year but got postponed given the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. While India, for varied reasons, could not achieve its FTP 2015 target of US $900 billion by 2020, the mid-term revision of US $1 trillion by 2024 also does not seem realistic.

Anxieties

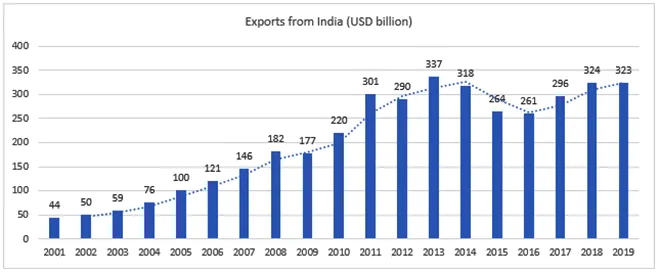

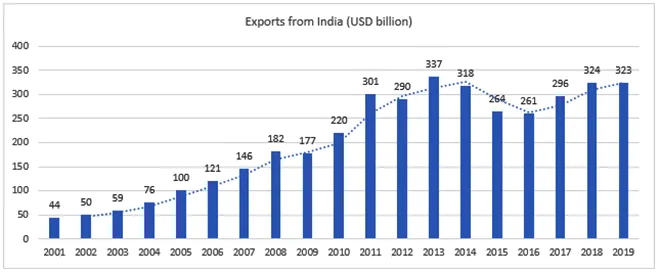

Absolute data in terms of exports shows that there has been an increase in India’s exports in the last two decades as it increased from US $44 billion in 2001, to US $220 billion in 2010, to US $323 billion in 2019 (the pandemic been an outlier in 2020).

While there has been export growth during the second decade of the century, it was largely been flat as compared to the first, which merits some concern. In fact, in 2001, India’s share in global exports stood at 0.7 percent, which doubled to touch 1.5 percent in 2010, but remained fairly around the same level in 2019 at 1.7 percent. The percentage of GDP exports has further fallen from 17 percent in 2011 to 12.4 percent in 2018.

Source:UN Comtrade, ITC; Author’s calculation

Source:UN Comtrade, ITC; Author’s calculation

India’s export-to-GDP ratio, when compared with some of its neighbours, exhibits a dim picture — while in India’s case, it has reduced from 25 percent in 2013 to touch 18 percent in 2019; Vietnam, on the other hand, has shown a perennial increase from 72 percent in 2010 to stand at 107 percent currently. Some of the emerging economies which have a higher export to GDP ratio over India are Thailand, South Korea, Mexico, South Africa, Philippines, Sri Lanka, and China.

On the other hand, the share of manufacturing as a percentage of India’s GDP has been hovering at around 15 percent for the longest time. The compounded annual growth rate of Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) received by Philippines has grown by 285 percent and Vietnam 102 percent during the 10-year period beginning 2010, as compared to 84 percent for India. Bangladesh’s FDI has also grown by 75 percent in the interim.

Opportunity post-pandemic

As the world recuperates from the pandemic, India has a huge opportunity to enhance its exports in the lowest possible time beating its contemporaries. The caveat for growth, however, remains if Indian policymakers exhibit complete belief and trust in their capability to fulfill domestic reforms to compete globally.

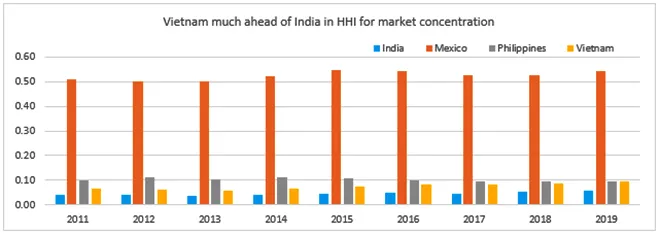

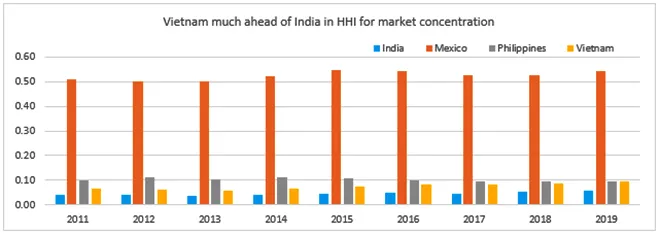

First is to expand India’s export markets. Sluggishness and lack of risk appetite is one of the major reasons for Indian exports failing to get its due. An analysis done through Hirschman Herfindahl Index (HHI) for market concentration of India’s exports was estimated to be 0.06 in 2019, up from 0.04 in 2011, indicating significant diversification of trade during these years. The HHI is a common measure of market concentration and is used to determine market competitiveness — greater the number, better it is.

Source: World Bank; Author’s calculation

Source: World Bank; Author’s calculation

In 2019, India’s top five merchandise export destinations accounted for about 37 percent of India’s total merchandise exports, as against 40 percent in 2011. While the figure shows an improvement, but when the HHI is compared with other emerging economies like Mexico, Philippines, and Vietnam, India indicates at being a relatively lower levels of market concentration — HHI stands at 0.54, 0.10, 0.09 respectively, as against India’s 0.06.

As an out of box measure to increase exports, the government may like listed export-oriented corporates to spend atleast 0.5 percent of their earnings yearly towards conducting seminars about market opportunities abroad. This could be akin to GOI’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiative wherein 2 percent of their average net profits is dedicated for the same. Many Indian companies are not even aware of the various sustainability and phytosanitary issues that are prevalent globally which holds them back from treading there. Hence, it is important to educate exporters, especially Micro, Small and Medium Enterprise (MSMEs) in India, which contribute more than 48 percent of India’s exports, who are often unaware of global laws and requirements.

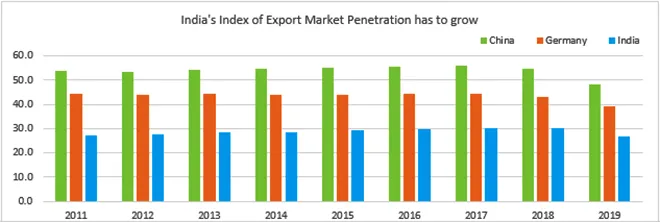

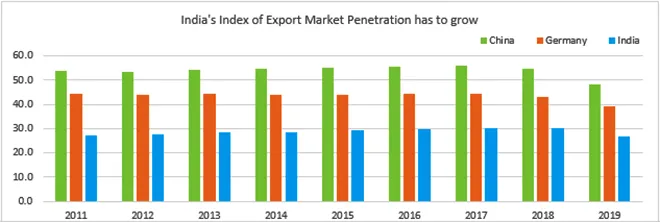

Secondly, as a corollary to the above, the country’s exports to its existing key destinations should also widen in product scope. For example, the Index of Export Market Penetration (IEMP) for India’s exports is estimated to be 26.8 in 2019, which is now lower than 27.1 in 2011, exhibiting that the growth potential in proven markets has not been fully tapped into, during the last 10 years. This is only possible by having a greater marketing network overseas. IEMP was reported to be the highest for China (48.1), the USA (40.6), and Germany (39). The IEMP measures the extent to which a country's exports reach already proven markets.

Source: World Bank; Author’s calculation

Source: World Bank; Author’s calculation

Thirdly, it is extremely important for India to diversify its export base by better integrating priority sectors with global value chains. It may be observed that a country like Vietnam, which has been an agrarian economy, has evolved, wherein more than 30 percent of exports are from technology-oriented electronic products.

Recently, GOI rolled-out targeted Production-Linked Incentives (PLI) schemes to create local industrial capacity, which is expected to benefit both local and foreign firms, while also possibly attracting some amount of FDI. It may be noted that India’s high-tech exports as a percentage of manufactured exports stood at around 10 percent, as compared to Malaysia (52 percent) and Vietnam (40 percent). Hopes are pinned on the PLI scheme to show some traction to improve the scenario.

Fourthly, a comprehensive package for the export-led growth in manufacturing and value-added agricultural sector, like a tax holiday, which would encourage investments and foster growth should be bought. Initially, the number of years could be linked to the sector and the investment being made by the firm, and consequently it can be linked to sales and exports, both.

Lastly, it is very important for Indian companies to participate in the global value chains. While many countries have been increasing import duties which reflects protectionism, the same should be extended with some sunset clauses. This will help Indian companies to know and believe that they need to improvise in the interim and not rely on protectionism for eternity.

India possibly had adequate reasons not to join the RCEP in 2020 as it found itself ill-prepared despite having started discussions in 2012 — but it cannot afford to give the same reason again. In conclusion, it is important to usher a favourable, realistic, and a doable export policy which is time-bound and helps India become capable of playing a greater role in global exports while competing with others.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV