-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

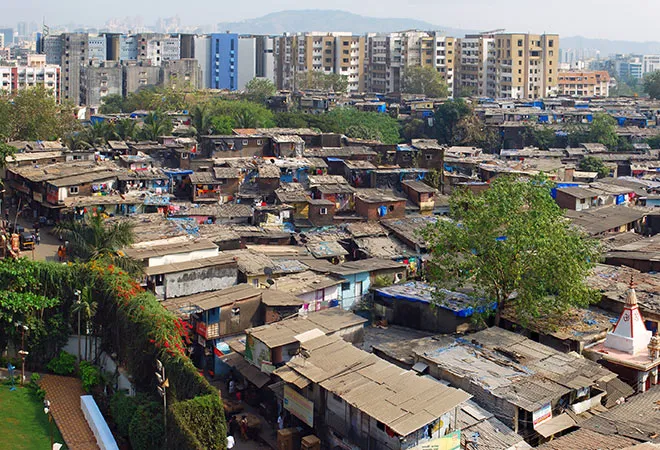

Frequent hand washing and physical distancing are being routinely prescribed as public health protocols against the spread of the coronavirus pandemic. But how about slums and squatter settlements where often ten to twenty people live cheek by jowl in tiny shanties and hundreds share community toilets? This is an issue of gigantic proportions. India’s urban slum population is larger than the population of Britain. According to Census (2011), there are 65 million slum dwellers. One in every six household in urban India live in slums. The proportions are much higher in metro-cities like Mumbai (41.3 percent), Kolkata (29.6 percent) and Chennai (28.6 percent). The slum dynamics need special focus in charting a post-pandemic recovery roadmap.

The pandemic is first and foremost an urban crisis, epicentres of which are the prime urban centres of the country. The districts classified under red-zone, includes all top-tier cities, which are fulcrums of Indian economy; gateways to international trade and commerce; and hubs of transportation and logistics networks. Prolonged lockdown of these strategic growth poles can hugely jeopardize economy and employment prospects across the country even if the rest of India is opened to business. Lives and livelihoods of people in India are increasingly interconnected. So as are the industry supply chains.

Spatial distribution of Indian economy is top-heavy and dominated by big cities. According to a McKinsey study 49 metropolitan clusters were projected to account for 77 percent of India’s incremental GDP, 72 percent of consuming-class households, and 73 percent of income pool between 2012 and 2025. However, economic growth in the cities had not generated labour intensive jobs in this age of outsourcing, contracting and automation. Research by World Bank economist Ejaz Ghani shows medium and large-scale manufacturing activities are also moving out of the big cities due to high land costs. Whereas, small scale informal sector trading and manufacturing are urbanising to take advantage of better infrastructure and business access. Livelihoods of the urban poor are almost entirely tied to the informal economy. Ejaz Ghani suggests the need to focus on small scale entrepreneurship to generate urban jobs.

Job scenario in Indian cities had been under severe stress in recent years, before being hit further by the COVID19 shock. According to Periodic Labour Force Survey (2017-18) urban unemployment rate at 7.8 percent is higher than rural unemployment rate of 5.3 percent. A recent study by CMIE shows that the lockdown has further worsened the job scenario. Worst hurt are the workers in the urban informal sector. People who depend upon daily income like street vendors, auto-rickshaw drivers, construction labour, carpenters, plumbers, waste pickers etc. are out of jobs for weeks together. The lockdown imposed for public health security, has snowballed into a grave humanitarian crisis for the migrant workers. A process of reverse migration has begun, as faced with loss of income, inadequate support for sustenance and harsh living conditions, millions of migrants have started returning to their rural roots.

Indian cities typically have an uneasy relationship with informality and labour mobility. Urban policies frequently equate informality with dysfunctionality, blight, and decay. Unskilled rural migrants are seen as burdens on city infrastructure. City beautification and environmental improvement drives often lead to forcible evictions of slums and squatter settlements, with taking their livelihood implications into consideration. The Covid-19 pandemic has further intensified these urban divides.

However, it is important to recognise that formal and informal economies are highly intertwined and reorient our urban policies. Informal workforce (including migrant labour) is vital for our cities to function. Several slum neighbourhoods are indeed vibrant economic clusters. For example, areas, such as: Dharavi -Mumbai (leather goods, packaged snacks and waste recycling), Metiaburj-Kolkata (kids’ garments), Jahangirpuri-Delhi (waste recycling) are indeed specialised production clusters linked to industry value-chains. Business models of these clusters derive their efficiency through cheap land and labour supply to micro-scale home-based enterprises, while for urban poor and recent migrants, they provide jobs and shelter. They often thrive by being creative, while negotiating extremely harsh living conditions. Several programmes in the past had sought to improve living conditions of the slum dwellers by relocation into proper housing at the outskirts of the city. But such projects ended up disrupting the livelihood ties of the people and failed.

The urban dimension of the COVID19 crisis has so far received only limited attention. Governmental attention is still preoccupied with the immediate task of crisis management, which is of course monumental in scale, and plagued by uncertainties. The administrative machinery is overstretched in enforcing quarantine regulations and emergency relief distribution. Nevertheless, as we are now moving towards phased relaxation of the lockdown, it is necessary to put in place a people-centric roadmap to restart our city systems, to avoid a repeat of the migrant crisis.

Several important welfares schemes such as universal basic income and direct cash transfer food subsidies through public distribution systems, and enhanced work opportunities through MGNREGA have been suggested in recent days to cushion the poor against livelihood disruptions. In addition to such national schemes, at city scale it is also necessary to simultaneously start planning for longer-term resiliency towards livelihood sustainability as health and economic concerns are closely intertwined – especially for the urban poor. When a daily wage earner falls sick, his income flows dry-up, and he sinks further into poverty-trap. Whereas, probabilities of a daily wage earner falling sick is also higher as they live under unhygienic surroundings.

To build long-term livelihood sustainability of the urban poor, it is imperative to take a more holistic approach, integrating objectives of employment generation and skill building along with hygiene and sanitation. One way to do this, would be to apply the principles of Sustainable Livelihood Framework, which takes a multidimensional approach towards reduction of the vulnerabilities by simultaneously focusing on financial capital (employment generation), physical capital (hygienic living environment), human capital (skill building). An area-based approach through spatial targeting of most vulnerable urban neighbourhoods in a comprehensive way, which simultaneously supports local micro enterprises, improves access to water supply, sanitation and shelter; and provides skill training, can go a long way in reducing vulnerabilities of the poor, generate jobs and spur bottom-up entrepreneurship.

Under the existing set of policy instruments, at the central government level, this would require bringing convergence between the Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana National Urban Livelihood Mission (DAY-NULM), the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana - Urban (PMAY-U) and the Swachh Bharat Mission – Urban (SBM-U).

The DAY-NULM supports building of finance capital and human capital. The scheme operates a wide grassroots level network of Area Level Federations which supports community based SHG (Self Help Groups) with vocational trainings, microfinance for start-ups and marketing of products by linking with e-commerce companies. Several SHGs are presently involved in Covid-19 related activities. For example, SHGs under Kerala’s Kutumbashree programme are running canteens for the migrant workers stranded because of the lockdown, while SHGs under Odisha’s Mission Shakti are stitching masks for the healthcare workers.

In recent years certain important steps have been taken towards convergence between the NULM and other missions. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs has released a guideline to bring convergence between the DAY-NULM and the SBM-U to upgrade the skills of manual scavengers and sanitary workers in solid waste management value chains. Similarly, a scheme has been formulated in Kerala to involve SHGs under DAY-NULM schemes to construct houses for the beneficiaries under the PMAY-U affordable housing programme.

These are certainly important steps. But, the DAY-NULM suffers operational deficiencies due to low budgetary allocation. In the last budget allocation DAY-NULM was only Rs 795 crore, as against Rs 9,210 crore allocated for the National Rural Livelihood Mission. To make significant impact in urban employment generation the DAY-NULM programme needs to be scaled up substantially. Recently, Odisha has announced Rs 100 crore ‘urban wage employment initiative programme.’ The scheme is made operational in all towns and cities of the state to help the livelihood deprived urban poor. Similar initiatives are also required to be taken by other states. Other state governments may initiate similar programs.

However, institutional capacity deficiencies in urban management and governance at the level of ULBs (Urban Local Bodies) are a major challenge in operationalising an integrated approach towards livelihood sustainability. Administrative systems of Indian cities are plagued by multiplicity of authorities and overlapping of jurisdictions. Functions regarding urban planning, economic and social development planning, and land use regulations are in almost all cases held at the state government level. While ULBs usually have control over solid waste management, but closely linked functions, such as Public Health, Sanitation, Water Supply and Transportation are often controlled by parastatal agencies.

Bringing convergence between multiple centrally funded projects and implementing the same through various local and state government agencies require high level administrative and managerial leadership. And that remains hugely problematic. Janagraha’s Annual Survey of India’s City Systems (2017) report based on survey of 26 cities, paints a dismal picture about municipal leadership deficits. Most states prefer to run the cities through appointed municipal commissioners rather than elected mayors. But the commissioners are frequently transferred, and the average tenure is only 10 months. Such frequent change of guard hampers smooth functioning of projects.

Achieving greater sustainability in livelihoods of India’s urban poor would require bringing greater alignment in urban management practices across multiples hierarchies of governance at city, local, state and national levels. Can we achieve that?

Frequent hand washing and physical distancing are being routinely prescribed as public health protocols against the spread of the coronavirus pandemic. But how about slums and squatter settlements where often ten to twenty people live cheek by jowl in tiny shanties and hundreds share community toilets? This is an issue of gigantic proportions. India’s urban slum population is larger than the population of Britain. According to Census (2011), there are 65 million slum dwellers. One in every six household in urban India live in slums. The proportions are much higher in metro-cities like Mumbai (41.3 percent), Kolkata (29.6 percent) and Chennai (28.6 percent). The slum dynamics need special focus in charting a post-pandemic recovery roadmap.

The pandemic is first and foremost an urban crisis, epicentres of which are the prime urban centres of the country. The districts classified under red-zone, includes all top-tier cities, which are fulcrums of Indian economy; gateways to international trade and commerce; and hubs of transportation and logistics networks. Prolonged lockdown of these strategic growth poles can hugely jeopardize economy and employment prospects across the country even if the rest of India is opened to business. Lives and livelihoods of people in India are increasingly interconnected. So as are the industry supply chains.

Spatial distribution of Indian economy is top-heavy and dominated by big cities. According to a McKinsey study 49 metropolitan clusters were projected to account for 77 percent of India’s incremental GDP, 72 percent of consuming-class households, and 73 percent of income pool between 2012 and 2025. However, economic growth in the cities had not generated labour intensive jobs in this age of outsourcing, contracting and automation. Research by World Bank economist Ejaz Ghani shows medium and large-scale manufacturing activities are also moving out of the big cities due to high land costs. Whereas, small scale informal sector trading and manufacturing are urbanising to take advantage of better infrastructure and business access. Livelihoods of the urban poor are almost entirely tied to the informal economy. Ejaz Ghani suggests the need to focus on small scale entrepreneurship to generate urban jobs.

Job scenario in Indian cities had been under severe stress in recent years, before being hit further by the COVID19 shock. According to Periodic Labour Force Survey (2017-18) urban unemployment rate at 7.8 percent is higher than rural unemployment rate of 5.3 percent. A recent study by CMIE shows that the lockdown has further worsened the job scenario. Worst hurt are the workers in the urban informal sector. People who depend upon daily income like street vendors, auto-rickshaw drivers, construction labour, carpenters, plumbers, waste pickers etc. are out of jobs for weeks together. The lockdown imposed for public health security, has snowballed into a grave humanitarian crisis for the migrant workers. A process of reverse migration has begun, as faced with loss of income, inadequate support for sustenance and harsh living conditions, millions of migrants have started returning to their rural roots.

Indian cities typically have an uneasy relationship with informality and labour mobility. Urban policies frequently equate informality with dysfunctionality, blight, and decay. Unskilled rural migrants are seen as burdens on city infrastructure. City beautification and environmental improvement drives often lead to forcible evictions of slums and squatter settlements, with taking their livelihood implications into consideration. The Covid-19 pandemic has further intensified these urban divides.

However, it is important to recognise that formal and informal economies are highly intertwined and reorient our urban policies. Informal workforce (including migrant labour) is vital for our cities to function. Several slum neighbourhoods are indeed vibrant economic clusters. For example, areas, such as: Dharavi -Mumbai (leather goods, packaged snacks and waste recycling), Metiaburj-Kolkata (kids’ garments), Jahangirpuri-Delhi (waste recycling) are indeed specialised production clusters linked to industry value-chains. Business models of these clusters derive their efficiency through cheap land and labour supply to micro-scale home-based enterprises, while for urban poor and recent migrants, they provide jobs and shelter. They often thrive by being creative, while negotiating extremely harsh living conditions. Several programmes in the past had sought to improve living conditions of the slum dwellers by relocation into proper housing at the outskirts of the city. But such projects ended up disrupting the livelihood ties of the people and failed.

The urban dimension of the COVID19 crisis has so far received only limited attention. Governmental attention is still preoccupied with the immediate task of crisis management, which is of course monumental in scale, and plagued by uncertainties. The administrative machinery is overstretched in enforcing quarantine regulations and emergency relief distribution. Nevertheless, as we are now moving towards phased relaxation of the lockdown, it is necessary to put in place a people-centric roadmap to restart our city systems, to avoid a repeat of the migrant crisis.

Several important welfares schemes such as universal basic income and direct cash transfer food subsidies through public distribution systems, and enhanced work opportunities through MGNREGA have been suggested in recent days to cushion the poor against livelihood disruptions. In addition to such national schemes, at city scale it is also necessary to simultaneously start planning for longer-term resiliency towards livelihood sustainability as health and economic concerns are closely intertwined – especially for the urban poor. When a daily wage earner falls sick, his income flows dry-up, and he sinks further into poverty-trap. Whereas, probabilities of a daily wage earner falling sick is also higher as they live under unhygienic surroundings.

To build long-term livelihood sustainability of the urban poor, it is imperative to take a more holistic approach, integrating objectives of employment generation and skill building along with hygiene and sanitation. One way to do this, would be to apply the principles of Sustainable Livelihood Framework, which takes a multidimensional approach towards reduction of the vulnerabilities by simultaneously focusing on financial capital (employment generation), physical capital (hygienic living environment), human capital (skill building). An area-based approach through spatial targeting of most vulnerable urban neighbourhoods in a comprehensive way, which simultaneously supports local micro enterprises, improves access to water supply, sanitation and shelter; and provides skill training, can go a long way in reducing vulnerabilities of the poor, generate jobs and spur bottom-up entrepreneurship.

Under the existing set of policy instruments, at the central government level, this would require bringing convergence between the Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana National Urban Livelihood Mission (DAY-NULM), the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana - Urban (PMAY-U) and the Swachh Bharat Mission – Urban (SBM-U).

The DAY-NULM supports building of finance capital and human capital. The scheme operates a wide grassroots level network of Area Level Federations which supports community based SHG (Self Help Groups) with vocational trainings, microfinance for start-ups and marketing of products by linking with e-commerce companies. Several SHGs are presently involved in Covid-19 related activities. For example, SHGs under Kerala’s Kutumbashree programme are running canteens for the migrant workers stranded because of the lockdown, while SHGs under Odisha’s Mission Shakti are stitching masks for the healthcare workers.

In recent years certain important steps have been taken towards convergence between the NULM and other missions. The Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs has released a guideline to bring convergence between the DAY-NULM and the SBM-U to upgrade the skills of manual scavengers and sanitary workers in solid waste management value chains. Similarly, a scheme has been formulated in Kerala to involve SHGs under DAY-NULM schemes to construct houses for the beneficiaries under the PMAY-U affordable housing programme.

These are certainly important steps. But, the DAY-NULM suffers operational deficiencies due to low budgetary allocation. In the last budget allocation DAY-NULM was only Rs 795 crore, as against Rs 9,210 crore allocated for the National Rural Livelihood Mission. To make significant impact in urban employment generation the DAY-NULM programme needs to be scaled up substantially. Recently, Odisha has announced Rs 100 crore ‘urban wage employment initiative programme.’ The scheme is made operational in all towns and cities of the state to help the livelihood deprived urban poor. Similar initiatives are also required to be taken by other states. Other state governments may initiate similar programs.

However, institutional capacity deficiencies in urban management and governance at the level of ULBs (Urban Local Bodies) are a major challenge in operationalising an integrated approach towards livelihood sustainability. Administrative systems of Indian cities are plagued by multiplicity of authorities and overlapping of jurisdictions. Functions regarding urban planning, economic and social development planning, and land use regulations are in almost all cases held at the state government level. While ULBs usually have control over solid waste management, but closely linked functions, such as Public Health, Sanitation, Water Supply and Transportation are often controlled by parastatal agencies.

Bringing convergence between multiple centrally funded projects and implementing the same through various local and state government agencies require high level administrative and managerial leadership. And that remains hugely problematic. Janagraha’s Annual Survey of India’s City Systems (2017) report based on survey of 26 cities, paints a dismal picture about municipal leadership deficits. Most states prefer to run the cities through appointed municipal commissioners rather than elected mayors. But the commissioners are frequently transferred, and the average tenure is only 10 months. Such frequent change of guard hampers smooth functioning of projects.

Achieving greater sustainability in livelihoods of India’s urban poor would require bringing greater alignment in urban management practices across multiples hierarchies of governance at city, local, state and national levels. Can we achieve that?

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Tathagata Chatterji is Professor of Urban Management and Governance at XIM (formerly Xavier Institute of Management), Bhubaneswar, India. His research interests are urban economic development ...

Read More +