-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Online threats to women in India have increased since the pandemic, but a combination of law enforcement, industry cooperation, and strategic partnerships could provide a strong counter

This article is part of the series — International Women's Day

In David Fincher’s 2002 thriller, Panic Room, a mother and daughter are forced to take refuge in a vault-like “panic room” when intruders break into their New York brownstone. Coming face-to-face with the three men could mean assault or even death. But locking oneself indefinitely in an inaccessible room, with only a bank of cameras as a window to the outside world, can be a terrifying experience too.

As risks to women in cyberspace multiply, there are no safe havens to which they can retreat and no fortified zones where they might wait out the threats to their dignity. A global survey shows that 60 percent of girls and women have faced harassment on social media platforms, and one-fifth of them have either quit or reduced their social media use as a result. Similarly, UN Women finds that 58 percent of girls and young women worldwide have experienced some form of online harassment, with trolling, stalking, doxxing, and other kinds of online gender-based violence (OGBV) emerging as the new dangers of the digital age.

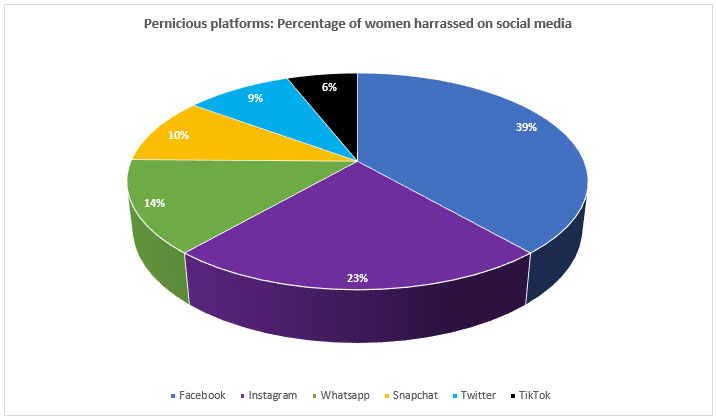

Source: Authors; figures compiled from YourStory.

India’s population of young people is the largest in the world and is the demographic that is most active online. The growing number of female Indian Internet users is a very positive development, but it has also put more women at risk in virtual spaces. Indeed, the incidence of online crimes against women—including sexual harassment, bullying, intimidation, threats of rape or death, cyberstalking, and the non-consensual sharing of images and videos—appears to be rising steadily.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau, reported cases of cybercrimes against women rose from 4,242 in 2017 to 8,730 in 2019. But it was the period of the COVID-19 pandemic and its attendant lockdowns that saw OGBV explode. Internet use in India surged by 50-70 percent during the long months of self-isolation, and by the end of 2021, the country’s internet user base had grown by nearly 37 percent. Women and girls began going online more frequently than ever before, and instances of OGBV and harassment increased exponentially. Four years after the COVID-19 outbreak, these egregious threats to women have not diminished.

The Indian government has acted to quell cybercrimes against women at various levels. These include establishing stringent legal frameworks, setting up reporting mechanisms, building the capacities of law enforcement agencies (LEAs), pushing for tech companies’ compliance with efforts to promote women’s online safety, and running awareness programmes for stakeholders.

The Rules also contain provisions to effectively curb revenge porn, by enjoining intermediaries to take down offending content within 24 hours of receiving a complaint from an affected individual.

The Information Technology (IT) Act 2000, for instance, seeks to protect citizens—and particularly women—by making the use of electronic means to violate bodily privacy, and to publish or transmit material that is obscene or contains sexually explicit acts punishable. Similarly, in a bold bid to make cyberspace safer, and more trusted and accountable, the IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021 require intermediaries to ensure that users do not host, upload, and share information that is “obscene”, “invasive of another’s privacy”, or “insulting or harassing on the basis of gender”. The Rules also contain provisions to effectively curb revenge porn, by enjoining intermediaries to take down offending content within 24 hours of receiving a complaint from an affected individual.

Reporting mechanisms offer a useful starting point for LEAs to swing into action, and the National Cybercrime Reporting Portal, which focused primarily on reporting sexually abusive content relating to women and children in its initial years, has been a first port of call for many victims. More recently, the mandate of the portal and an accompanying helpline have been expanded to allow the reporting of all types of cybercrime. The government also runs the “Cybercrime Prevention against Women and Children” (CCPWC) scheme to build awareness about OGBV and related crimes, train LEAs and improve cyber forensic capabilities. Advocacy and capacity development—often carried out in partnership with tech platforms and civil society organisations (CSOs)—continue to be a mainstay of the government’s efforts to promote women’s safety online.

Even as the interventions of the central and state governments provide a foundational layer of defence against OGBV, the onus remains squarely on technology companies to act as well. Today, most tech platforms have content standards and community guidelines prohibiting material that aims to harass women or compromise their safety. Social media platforms also routinely use AI and machine learning (ML) to detect and remove offending comments. As early as 2018, for example, Instagram had begun using ML to identify violent and abusive language against women; and virtually every major platform—Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube, among others—includes content reporting mechanisms and user blocking tools.

The government also runs the “Cybercrime Prevention against Women and Children” (CCPWC) scheme to build awareness about OGBV and related crimes, train LEAs and improve cyber forensic capabilities.

Tech giants are also increasingly partnering with civil society to strengthen women’s safety. A recent standout initiative is Meta’s launch of StopNCII.org in India, in collaboration with several Indian CSOs. This is a pioneering platform that seeks to fight the spread of non-consensual intimate images (NCII). Simultaneously, Meta has also rolled out the Women’s Safety Hub, available in multiple Indian languages, that provides women with tools and resources for staying safe online.

Creating safe online environments is essential for upholding women’s dignity, ensuring their digital well-being, and supporting their fundamental right to the Internet. It also makes for smart economics. As the International Telecommunication Union has observed, bringing and keeping 600 million more women online could boost global GDP by US$ 18 billion.

The key building blocks for combatting OGBV and allied risks in India are largely in place. However, the enforcement of existing laws and policies could be strengthened; and the private sector, especially Big Tech, needs to be significantly more proactive in complying with regulatory requirements besides upping its own game for tackling online harms.

Creating safe online environments is essential for upholding women’s dignity, ensuring their digital well-being, and supporting their fundamental right to the Internet.

While the Indian Penal Code, IT Act 2000, and IT Rules 2021 provide a legal bedrock for punitive measures against offenders, perhaps it is also time to amend the Indecent Representation of Women (Prohibition) Act 1986 to include virtual spaces—a proposal that has lain before the Parliament for nearly a decade. Moreover, Indian courts have allegedly tended to attach greater importance to offline crimes against women than online ones. In cases where an accused person is charged with both online and offline offences, there is reportedly a tendency to focus more on his offline offences. Such an imbalance, if there is one, ought to be rectified, with justice being served equally irrespective of the locus of a crime.

At the same time, tech platforms and Internet intermediaries—the primary sites for OGBV—need to demonstrate far greater accountability. As the UN Broadband Commissioner pointed out, intermediaries ought to “set high-level and clear commitments to uphold women’s and girls’ safety in online spaces”. These commitments should be operationalised by systematically improving tools to “prevent, detect, respond to and monitor online violence”, and for “filtering, blocking and taking down illegal content […] whenever required”. Finally, CSOs have an important role to play, collaborating with governments and businesses to strengthen digital literacy, manage specialised awareness programmes, and develop resources to promote online safety. A combination of all these measures could go a long way towards building a safer cyberspace for women.

Anirban Sarma is the Deputy Director and a Senior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation

Shrushti Jaybhaye is a Research Intern at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Anirban Sarma is Director of the Digital Societies Initiative at the Observer Research Foundation. His research explores issues of technology policy, with a focus on ...

Read More +

Shrushti Jaybhaye is a Research Intern at the Observer Research Foundation ...

Read More +