-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

EdTech needs to ensure that the future of education is equitable, inclusive, and safe, and does not hamper innovation at the cost of over-regulation

The pandemic has drastically changed the nature of social interactions across the world. As people were confined to their homes due to lockdowns, the rapid adoption of alternative measures that sought to bring a semblance of normalcy was seen across contexts—from communication and work to health and commerce. Digital technologies played a key role in this shift, particularly in education.

The pandemic has accelerated the integration of digital tools into all aspects of the educational process—from personnel management to pedagogy and assessment. Indeed, the advantages are multifold; proponents claim that edtech plays a pivotal role in making teaching more transparent and enhances learning experiences by immersing students in experiential education through Augmented/Virtual Reality (A/VR). Moreover, such solutions may help democratise education by opening learning opportunities to all ages and genders, removing institutional barriers of entry for those looking to upskill, thereby propelling the creation of an able and agile workforce. These, in turn, may help reduce inequalities and drive greater societal inclusion.

It is, however, important to investigate these claims in light of the risks edtech poses. Scholarly literature finds this narrative of ‘edtech solutionism’ rather reductionist—asserting that the correlation between technological interventions and good learning outcomes is simplistic, reducing the complexities of the teaching-learning process into mere content production, and creating into a performative learning environment. Present edtech solutions don’t reflect the non-linearity of pedagogy and unchecked growth may lead to a culture of “machine behaviourism”—where learning is dictated by artificial intelligence (AI) and extreme behavioural practices, which may diminish student agency. Further, there is little evidence on the efficacy of edtech itself, and a market-driven approach without responsible regulation may risk exacerbating the digital divide, favouring the already well-off.

Discourse on edtech seems to focus predominantly on its potential to catalyse the innovation economy. While important, the apparent deification of its ability in fixing “whatever’s broken in education” takes attention away from the risks posed by its underlying technologies on human agency, autonomy, privacy, and well-being. Like other internet platforms, edtech platforms collect data and deploy algorithms to personalise a learner’s experience. However, safeguards on the collection and use of edtech-specific data are largely absent in regulations today prompting the possibility of such practices to clinically profile, hyper-nudge, and manipulate users. Reports of certain edtech products collecting biometric data (like heartbeats and retina movements) to monitor and predict moods and stress levels are symptomatic of a larger student surveillance culture, which might have problematic ramifications if left unchecked.

As the internet undergoes a paradigm shift with AI and the metaverse gaining popularity, policymakers and technologists must plan for the future of edtech governance under conditions of deep uncertainty.

As children and adolescents are primary beneficiaries of such applications, the lack of uniform minor and youth safeguards (both in-product and through regulation) puts them at risk of harm. 5Rights Foundation, a UK-based child rights organisation, identifies three broad classes of risks that edtech platforms may pose: Content risks—exposure to inappropriate content, contact risks—risk of exposure to antisocial individuals, and contract risks—concerns with pervasive data collection. Despite children comprising a third of internet users, the lack of minor-centric design in most edtech solutions today paint a worrying picture of the future of digital education.

Furthermore, as governments continue to deploy edtech, important considerations on their large-scale procurement, baseline requirements for vendors and appropriate oversight mechanisms must be factored into policy planning. This will have long-term implications on the competitiveness of the edtech market and prevent the creation of virtual monopolies. Finally, as the internet undergoes a paradigm shift with AI and the metaverse gaining popularity, policymakers and technologists must plan for the future of edtech governance under conditions of deep uncertainty.

The road ahead

The generative nature of technologies that power edtech today dictates that along with positive innovation, risks will continue to proliferate. However, placing clampdowns with the intent of mitigating harm will only hinder chances of harnessing their potential. Parallelly, we cannot afford to solely rely on ex-post mechanisms that seek to undo the damage that has already been done. The need of the hour is to create iterative and collaborative pathways that help realise these objectives. We must therefore seek to responsibly innovate edtech.

There is, however, an urgent need to conduct further evidence generation and integrate such frameworks into edtech governance, so that the future of education is equitable, inclusive, and safe, and does not hamper innovation at the cost of over-regulation.

This is not to say that action hasn’t taken place. Standards set by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers’ (IEEE) on age-appropriate design and data governance frameworks, the UK’s Age-Appropriate Design Code, the United States’ Children Online Privacy Protection Act, and the Australian e-Safety Commissioner’s Safety-By-Design Principles are promising examples in this regard. The Indian EdTech Consortium’s efforts in developing a self-regulatory code of conduct for accessible quality education is a good example of a novel governance approach required for this space. Further, broader risk-based frameworks by the EU on AI and digital services also help to shape this emerging regulatory enterprise.

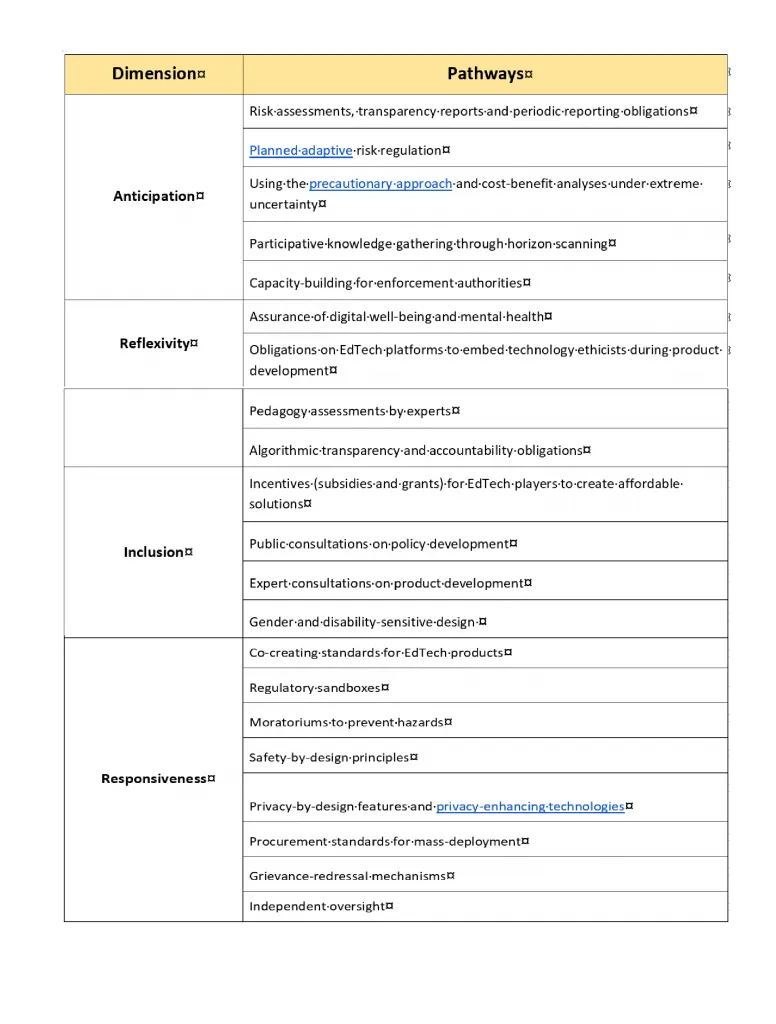

There is, however, room for concerted action. Approaches driven by responsible innovation may act as guides for policymakers and technologists seeking to develop fit-for-purpose frameworks. The framework used below considers four dimensions: anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness, and applied to edtech, it may enable pathways for safe digital learning.

Indeed, this serves as a template for regulators to determine the course of policy, and its appropriation must be done after careful analysis of a country’s context. There is, however, an urgent need to conduct further evidence generation and integrate such frameworks into edtech governance, so that the future of education is equitable, inclusive, and safe, and does not hamper innovation at the cost of over-regulation.

Indeed, this serves as a template for regulators to determine the course of policy, and its appropriation must be done after careful analysis of a country’s context. There is, however, an urgent need to conduct further evidence generation and integrate such frameworks into edtech governance, so that the future of education is equitable, inclusive, and safe, and does not hamper innovation at the cost of over-regulation.

Siddhant Chatterjee is a Policy Consultant.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Siddhant Chatterjee is a Policy Consultant. He's previously worked with the British and Australian Governments and his interests lie in AI Ethics and Platform Governance.

Read More +