-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The UK’s Rwanda Act has big implications for not just the West but for the Global South

When Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was elected in late 2022, he vowed to “stop the boats”. He was referring to the forced migrants who enter the United Kingdom (UK) using illegal, dangerous, and often unnecessary methods, primarily by boat. Consequently, on April 22, a law was passed by the British Parliament that permits any illegal asylum applicants to be deported to East African country Rwanda and, then be barred from ever entering the country again.

However, since there is no refugee visa or other legitimate means of entry, the rule essentially means that all asylum seekers are prohibited from entering the UK. The plan calls for sending anyone who entered the country illegally after 1 January 2022 to Rwanda. Thus, if this law gets implemented, it is likely that the 50,000 asylum seekers who are currently in the UK might eventually be deported to Rwanda. The top five countries seeking asylum in UK, arriving by boat are Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh.

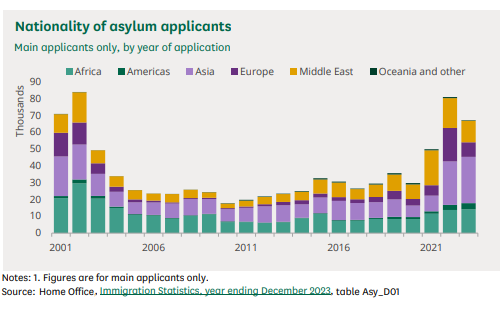

The genesis of the law goes back to April 2022 when Rwandan President Paul Kagame and Britain’s then Prime Minister Boris Johnson signed an agreement known as the ‘Migration and Economic Partnership’, or ‘Rwanda Plan’ that would allow Britain to deport anyone seeking asylum to Rwanda. As the number of refugees coming by boat to the UK in 2022 rose to a record 45,774 from a mere 299 in 2018, immigration has emerged as an increasingly highly-debated issue in the UK parliament.

Nonetheless, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) deemed the law as illegal and prevented the first deportation flight from taking place in June 2022. Furthermore, the British Supreme Court in November 2023 upheld its decision declaring the scheme illegal due to the possibility of persecution of these asylum-seekers in their home countries or other nations, such as Rwanda, if migrants were returned. This would violate both British and international human rights laws and accords.

The economic rationale of the decision stems from the fact that Britain continues to spend more than 3 billion pounds annually in handling refugee claims.

In response to the concerns expressed by the Supreme Court, PM Sunak proposed the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Act, a new deal with Rwanda. In essence, the new act will override all legal barriers and declare Rwanda safe for asylum seekers. Additionally, this new law will also prevent Rwanda from sending any of its refugees to any other country except back to Britain.

The economic rationale of the decision stems from the fact that Britain continues to spend more than 3 billion pounds annually in handling refugee claims. Further, the daily expense of accommodating these migrants in hotels and other lodgings until their application is processed also exceeds approximately 8 million pounds every day. As a matter of fact, Rwanda has already received more than 200 million pounds from Britain prior to any deportations, and it is expected to receive another 600 million pounds or even more to resettle the 300 refugees. Meanwhile, the law has drawn harsh criticism from everyone—from Sunak’s own Conservative Party to the UN human rights commissioner.

Notwithstanding the repeated allegations against the government of violating human rights, the Rwandan government’s eagerness to take in these migrants shouldn’t incite animosity towards the nation. The nation has endured arguably the largest genocide in recent history, and it remains a living example of tenacity, resiliency, and survival today.

Many Rwandans today have a stronger bond with migrants as a result of the Hutu-led mass extermination and persecution of Tutsis during the civil war. In addition, more recently and largely unrecognised by the West, a large number of migrants are still coming to Rwanda from neighbouring countries such as DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo) or Burundi in order to escape the horrific violence those countries are experiencing.

Under a UNHCR collaboration, in recent years, Rwanda has taken in refugees who were evacuated from the infamous detention centres in Libya on multiple occasions.

There are presently about 135,000 refugees in Rwanda, according to a 2023 study published by Refugees International. In contrast to many other countries, refugees in Rwanda are allowed to live freely in their own homes, work, own property, register businesses, and open bank accounts. Actually, Rwanda’s refugee policies pertaining to “economic inclusion” “stand out as a model with lessons for East Africa and beyond.” Under a UNHCR collaboration, in recent years, Rwanda has taken in refugees who were evacuated from the infamous detention centres in Libya on multiple occasions. Additionally, the nation was also part of the contentious and now-defunct deal of accepting asylum seekers rejected by Israel and received about 4000 refugees deported by Israel.

Notwithstanding the history of Rwanda, the ongoing law is about to take effect. The British premier has stated that the first flight will take off in 10 to 12 weeks. Although Rwanda’s ability to accommodate such a high number of refugees is called into doubt, the greater concern is the precedent this law may establish for the rest of Europe. In fact, a number of European nations have started to indicate their willingness to enact similar laws. They are, in most likelihood, watching over the UK’s experiments to develop their own offshore model of migration management.

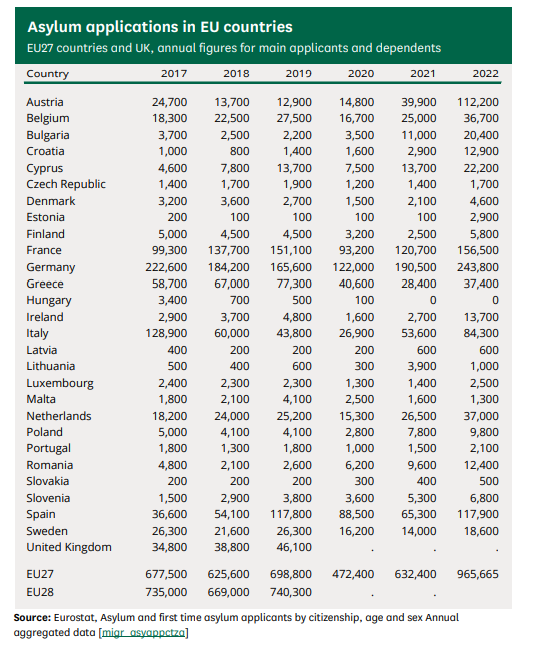

In fact, the UK is by no means the only nation that wishes to cut back on the money they spend on aiding others. The conservative opposition in Germany supports sending future refugees to non-EU European nations like Moldova and Georgia, or to third countries like Ghana and Rwanda in Africa, where their asylum claims can be processed. Meanwhile, Italy is considering deporting its asylum seekers to Albania and the Albanian parliament has already ratified the deal and may receive 36,000 refugees annually. Austria has also indicated interest in implementing similar programmes.

In addition to the future of these asylum seekers, there would be many more pressing worries for the host countries. What, for instance, should citizens do in the event that migrant groups begin to vie with one another for scarce resources or jobs? Even while the West might not openly endorse forced migration, it is callous to divert their boats to another nation. As a matter of fact, despite the shadow of the imminent Rwanda policy, more than 6,250 people have reached the UK by crossing the English Channel in boats so far this year.

By diverting the boats, Britain may prevent them from reaching the British shores. However, this won’t deter these asylum seekers from escaping their own nations. Given their diverse national backgrounds and the propensity for violence and social unrest in their home countries, these refugees might assume even higher risks. Denying them institutional support until there is peace in their home countries would be a grave injustice to those who are in need of it.

The architecture of the global protection regime will be fatally and completely undermined by such a unilateral policy of closed borders.

It is obvious that “stopping the boats” is an oversimplified solution to a complex challenge. Indeed, forced migration is a significant challenge for many Western countries. Unfortunately, there isn’t any easy fix available for it. To handle the problem in the short- to medium-term, nations have no other option but to cooperate. Furthermore, the UK’s agreement with Rwanda to divert, prevent, and ignore the problem of forced migration is vehemently inhuman, excessively costly, and inefficient. Most importantly, the architecture of the global protection regime will be fatally and completely undermined by such a unilateral policy of closed borders.

The level to which protests against the law are taking place communicates an unequivocal message: Those who require migration are still welcome by the common people. While the full-blown effects of the Rwanda Act are yet to be seen, surely many countries of the Global South may consider the migration outsourcing service as an easy way of attracting investment, and this could spur a race to the bottom. The result of this slippery slope will be a lose-lose for the Global South.

Samir Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Samir Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow at ORF where he works on geopolitics with particular reference to Africa in the changing global order. He has a ...

Read More +