Monkeypox (MPX) is a rare, viral zoonotic disease with symptoms similar to what was seen in smallpox patients in the past, although clinically less severe with a much lower mortality rate. The disease was

first seen in 1958 when two pox-like outbreaks were seen in monkeys that were being used for research. While the disease is called monkeypox, the source of the pathogen remains unknown. It is thought that many species of

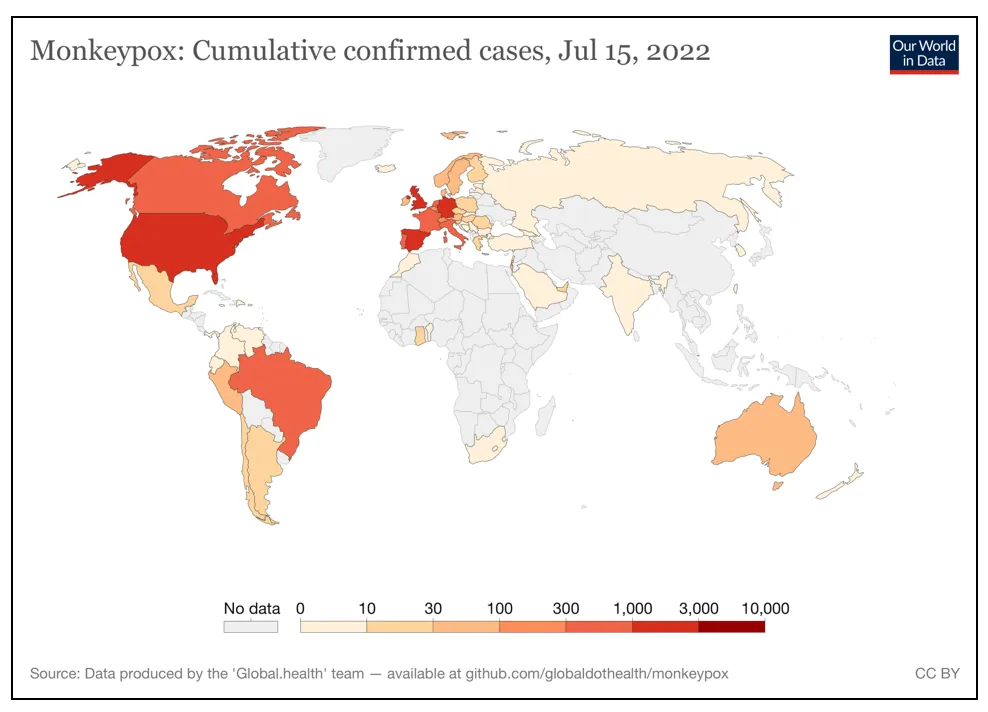

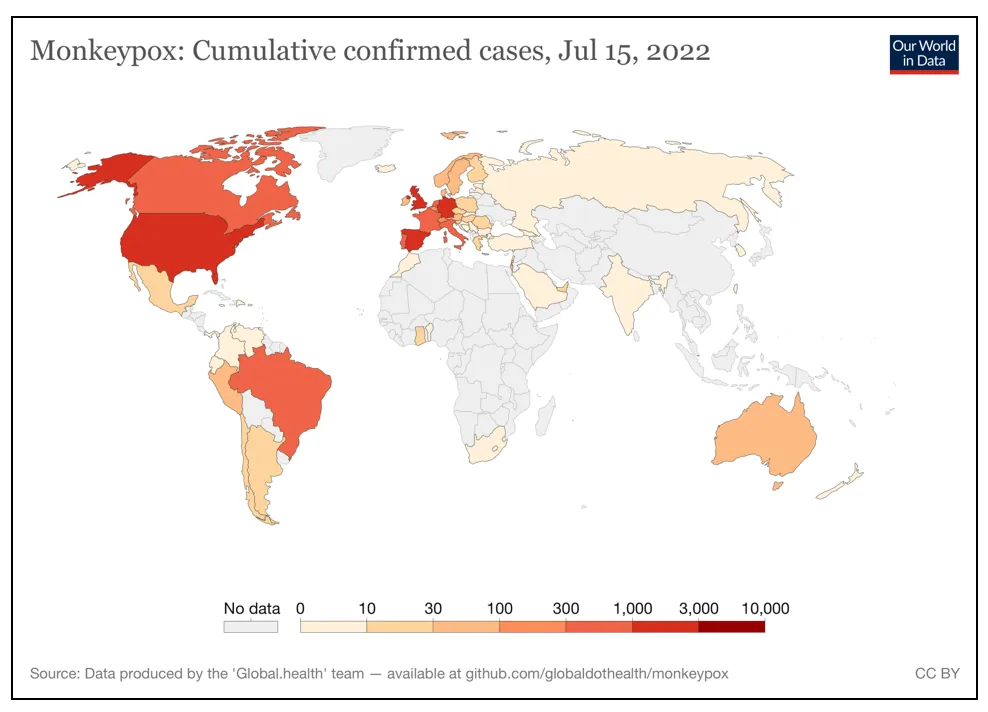

rodents harbour the virus and can infect humans. Monkeypox caught the world’s attention again when cases emerged from countries that were non-endemic to the virus with no epidemiological links to any endemic areas. As of 15 July, 2022,

12,669 cases of monkeypox infections have been reported across 62 countries globally.

India reported its first case of monkeypox on 14 July, from the state of Kerala.

Figure 1: Cumulative confirmed Monkeypox cases as of 15

th July, 2022

Where did it come from?

Where did it come from?

Thanks to the advancement in technologies such as genetic analysis, the

origin of the monkeypox outbreak are now becoming clearer. Researchers believe that the virus has been circulating in humans since 2018. There had been an MPX outbreak in Nigeria in 2017, and researchers believe that the

current virus is a descendant of the 2017–2018 Nigeria outbreak. They observed that the virus

mutated at a much faster rate than expected. This may have allowed it to adapt to its human host in a much better way. However, more research is needed to understand its implication on transmissibility and severity.

Emerging infectious diseases and ‘One Health’

The

2017-2018 monkeypox outbreak in Nigeria had widespread geographic distribution. While monkeypox is endemic to Central and West Africa, there were certain observations reported from the 2017–18 outbreak in Nigeria that are relevant to the present situation. It was reported that the cases which were across various regions were not epidemiologically linked but were genetically similar to the 1970 virus which could mean that the virus was prevalent in the country for many decades in an unidentified animal reservoir. This could mean that the monkeypox outbreaks could be occurring throughout the country by spillovers from animal reservoirs. In the case of

zoonotic infectious diseases, in an outbreak, the spillover of the pathogen from an animal reservoir into the human population matters, which is influenced by a variety of factors. The nature (with RNA viruses being more prone to spill over into an animal or a human host) and dynamics of the pathogen in the host reservoir population influence the risk to human health. Various factors of the reservoir population such as density, behaviour, contact patterns, and levels of immunity, influence the risk of spillover. This is also why outbreaks vary according to season, location, and climate. The transmissibility and virulence of the pathogen also influence the chances of the outbreak turning into an epidemic.

While monkeypox is endemic to Central and West Africa, there were certain observations reported from the 2017–18 outbreak in Nigeria that are relevant to the present situation.

All zoonotic infectious diseases come from animal reservoirs, which puts the “One Health” perspective in the spotlight. “

One Health” is a collaborative, multisectoral and transdisciplinary approach working at the local, regional, national, and global levels to achieve optimal health outcomes recognising the interconnection between people, animals, plants and their shared environments.” It acknowledges that the health of people, animals and the environment are connected to and impact one another. To achieve optimum human health, the good health of plants and animals is of paramount.

Africa has

several emerging and reemerging infectious diseases that plague the continent with very poor health infrastructure to tackle them. Armed conflict, urbanisation, and deforestation provide optimum conditions for zoonotic diseases to spill over and spread. Poor sanitation and hygiene, rising hunger levels, high population densities and sub-optimal water levels provide optimum conditions for the pathogens to spread in the population. There is not much collaboration in the

One Health networks in Africa. The monitoring and evaluation programmes require structure. There is still a lot of work to be done in terms of disease surveillance, monitoring and control. Most of the funding that Africa receives for its One Health initiative is from outside the continent and to make One Health sustainable in Africa, that needs to change. Advocacy, communication, and awareness about One Health need to be spread to help

institutionalise and engrain the concept in the communities. Public-private partnerships need to be encouraged. Good governance, cooperation, and collaboration between different sectors are key to the success of any One Health initiative in Africa.

Has Africa been neglected before?

The recent multi-country monkeypox outbreak urges us to look at the neglect and unfair treatment that Africa faces from the international community. The monkeypox outbreak is just another example where the world has not paid attention to the crises running rampant in Africa. After the outbreak spread to the West, the higher-income countries started securing doses of the smallpox vaccine manufactured by Bavarian Nordic but this

vaccine is not available anywhere in Africa, where monkeypox has been endemic in some countries for a very long time.

Researchers have also shared their findings warning that cases in Sub-Saharan Africa were rising with symptoms similar to those that are seen in the current outbreak. Between 1 January 2020 and 28 November 2021, the Democratic Republic of Congo reported

9,175 cases of MPX. Unfortunately,

adequate resources such as genomic surveillance equipment and funding were not provided to researchers. However, after it spread to other countries, authorities started paying attention.

Most of the funding that Africa receives for its One Health initiative is from outside the continent and to make One Health sustainable in Africa, that needs to change.

As seen with COVID-19, Africa faces inequities with vaccines, diagnostics, surveillance, and funding. Africa was subject to vaccine inequity during the COVID-19 pandemic as well. According to Our World in Data, by 1 January 2022, when the world was dealing with Omicron, the United Kingdom (UK) had already administered the booster (third dose) shots to

50 out of every 100 people while Europe and other high-income countries had provided booster doses to 24 and 25 people out of every 100, respectively. At that point, Africa had only

8.99 percent of its population that was fully vaccinated (two doses). Africa had not even vaccinated its population with the required two doses while higher-income countries were already providing the third dose to their population. After the discovery of Omicron, there were travel restrictions imposed on Africa instead of applauding it for its surveillance while high-income countries doubled down on their vaccinations.

During the Ebola outbreak in Africa, the higher-income countries failed to provide the disease-stricken countries with the support they needed. Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), an international organisation battling the disease in Africa, could not cope with the outbreak. They requested international assistance. However, they reported that the response was

“too little, too late”.

Paul Farmer and Jim Yong Kim, renowned for their work in global health, and co-founders of the non-profit Partners in Health, said that if the disease struck cities in the United States, the effective health systems in place would have contained and eliminated the disease. They believe that if the rich countries led a public health response in Africa, the disease could be contained and the mortality rate would be lowered.

After the outbreak spread to the West, the higher-income countries started securing doses of the smallpox vaccine manufactured by Bavarian Nordic but this vaccine is not available anywhere in Africa, where monkeypox has been endemic in some countries for a very long time.

There are

other crises in Africa, most of which are not shared with the rest of the world. Violence, rising hunger levels, and widespread displacement, to name a few. Poor media attention reduces the awareness and funding that these crises get which worsens the situation. In response to the tragic war in Ukraine, the international reaction was swift. Countries came together to condemn the aggression by Russia. Private companies and governments donated generously while the media covered the situation the entire time. The war in Ukraine has pushed the crises in Africa further into the shadows. The international response toward Ukraine is a great example of what cooperation and global solidarity can do for a nation in crisis. We must direct this towards Africa and not neglect it any further. The Monkeypox outbreak is just a small example of the price the world is paying for neglecting Africa.

Improving funding for research, investments in specific projects, improving the healthcare infrastructure, creating awareness, and paying attention to the continent can help avoid another epidemic and tackle the ongoing ones. As we have seen from the monkeypox outbreak, they have the potential to spread across the globe. The COVID-19 pandemic and the monkeypox outbreak teach the international community the importance of global solidarity for if these crises cannot, then perhaps nothing can.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Monkeypox (MPX) is a rare, viral zoonotic disease with symptoms similar to what was seen in smallpox patients in the past, although clinically less severe with a much lower mortality rate. The disease was

Monkeypox (MPX) is a rare, viral zoonotic disease with symptoms similar to what was seen in smallpox patients in the past, although clinically less severe with a much lower mortality rate. The disease was

PREV

PREV