-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

India’s biofuel journey marks a strategic shift toward sustainable transport, highlighting key milestones and challenges that shape its future path

Image Source: Getty

The road transport sector, a cornerstone of India’s economic framework, is also one of the largest oil consumers, accounting for 44 percent of the total consumption in 2021. Petroleum-based fuels, including petrol and diesel, fulfil 95 percent of the sector’s energy requirements, with alternative energy sources, including natural gas, electricity, and biofuels, contributing the remainder. While the transport sector is responsible for approximately 12 percent of India’s total carbon emissions, per capita emissions from road transport have risen by 2.5 times since 2000.

The number of registered motor vehicles, mostly powered by internal combustion engines (ICEs), reached 326.3 million in 2020. Without effective transitioning to cleaner fuels, Co2 emissions from the transport sector could rise by as much as 60 percent by 2050. Therefore, decarbonising the transport sector is critical for sustainable climate action. Transitioning to cleaner, low-carbon alternatives, such as biofuels, can significantly reduce the reliance on fossil fuels and mitigate the sector’s environmental impact.

Figure 1 showcases India’s journey towards Ethanol Blending Petrol (EBP)programme:

| Year | Government Initiative |

| 2014-15 |

● Reintroduced the price mechanism for ethanol procurement ● Introduction of Alternate routes for ethanol production (2nd generation, including petrochemical) ● Easing the tender conditions for the setting up of bio-refineries |

| 2015-16 | ● IDR Act amendment to clarify the roles of the Central and state governments for uninterrupted supply of ethanol for blending. |

| 2016-17 | ● Regular interaction with the state and all other stakeholders to address issues pertaining to the Ethanol Blending Programme (EBP). |

| 2017-18 | ● Notified forward-looking and updated National Policy on Biofuels- 2018, involving all stakeholders |

| 2018-19 |

● Interest subvention scheme for enhancement and augmentation of ethanol production capacity in the country ● Allowed conversion of B heavy molasses, sugarcane juice, and damaged food grains to ethanol. |

| 2019-20 |

● Opened a fresh window for inviting applications under the interest subvention scheme. ● Extension of EBP programme to the whole of India ● New source of sugar & sugar syrup introduced for ethanol production and fixed remunerative price. ● Published “Ethanol Procurement Policy on a long-term basis under the EBP programme” |

| 2020-21 |

● Enhanced OMCs capacity for ethanol storage from 5.3 crore litres in 2017 to 17.8 crores litres in December 2020. ● The beginning of one-time registration of ethanol suppliers for the long term. ● Opened a fresh window for inviting applications under the interest subvention scheme. ● Approval of the National Biofuel Coordination Committee (NBCC) to utilise surplus stock of rice lying with the Food Corporation of India (FCI) for ethanol production. ● Approval of NBCC to utilise maize for ethanol production |

| 2021-22 | ● Interest subvention scheme for enhancement and augmentation of ethanol production capacity extended to gain-based distillers and distillers producing ethanol from other feedstocks like sugar beet, sorghum, apart from molasses-based distilleries. |

Source: Roadmap for Ethanol Blending in India 2020-25

The Indian federal authority has pursued a systematic, incremental methodology to advance ethanol admixture as a constituent of its overarching energy security and environmentally-viable fuel alternatives paradigm. Commencing in fiscal year 2014–15, a sequence of policy interventions was enacted to catalyse ethanol synthesis, rationalise regulatory protocols, and broaden admixture implementation.

Critical junctures encompass the re-establishment of a price-based procurement system for ethanol and the introduction of divergent production pathways in 2014-15. Subsequently, amendments to the Industries (Development and Regulation) Act in 2015-16 delineated jurisdictional responsibilities between central and provincial governance, fostering a more seamless supply network. Periodic dialogues with industry participants were initiated in 2016-17 to mitigate impediments within the Ethanol Admixture Program (EAP).

The 2021-22 extension of fiscal facilitation to ethanol distillation facilities employing non-molasses feedstocks further diversified the sector, positioning India towards a more ecologically sustainable and domestically autonomous biofuel infrastructure.

A pivotal achievement was the 2018 National Biofuels Policy, which established a prospective regulatory architecture. Subsequent fiscal periods witnessed measures such as interest rate subsidies to augment ethanol production capabilities, the integration of novel raw materials, including sugarcane extract and degraded cereal grains, and the nationwide dissemination of the EAP during 2019-20.

By FY 2020-21, ethanol storage infrastructure had expanded threefold, and authorisation was granted for the utilisation of surplus rice and maize in ethanol manufacturing. The 2021-22 extension of fiscal facilitation to ethanol distillation facilities employing non-molasses feedstocks further diversified the sector, positioning India towards a more ecologically sustainable and domestically autonomous biofuel infrastructure.

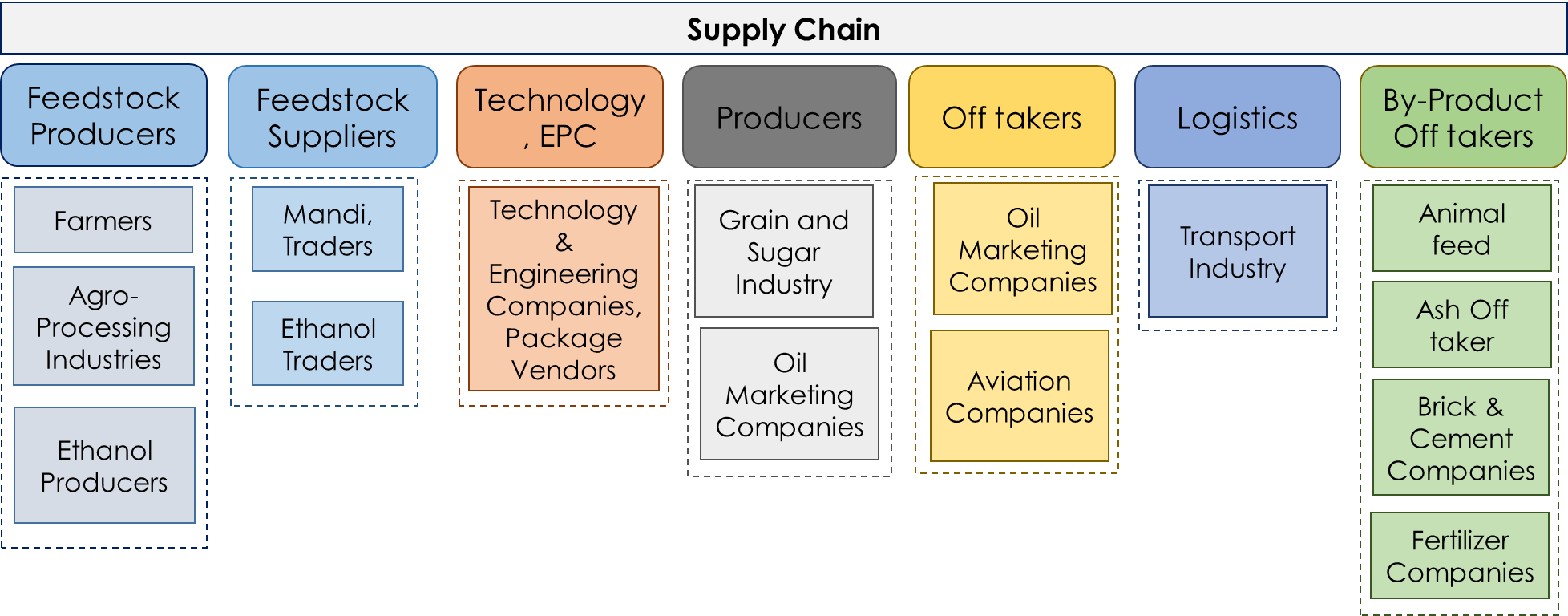

India’s biofuel production ecosystem involves seven critical players, as shown in Figure 2.

Source: Compiled by the Author

Feedstock producers: Feedstock producers, including farmers and agro-processing industries, supply the raw materials for first-generation (1G) ethanol, second-generation (2G) ethanol, Compressed Biogas (CBG), and Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF). 1G ethanol feedstocks comprise sugary raw materials (sugarcane, molasses, sweet sorghum, sugar beet, amongst others) or starchy (broken rice, corn, and cassava). 2G ethanol utilises lignocellulosic biomass, such as cane bagasse, leaves, trash, cotton and soya stalks, cereal straws (rice, wheat, corn), corn cobs and stover, grasses (napier, bamboo), palm residues, and soft/hardwoods. CBG production, on the other hand, utilises pressmud (a residual byproduct of the sugarcane industry), cereal straws, cane bagasse and trash, Napier grass, cotton/soya stalks, and empty fruit bunches. SAF production utilises low-carbon feedstocks, including 1G ethanol.

OMCs are the primary consumers of bioethanol and biodiesel, blending them with conventional fuels to meet mandated blending targets.

Feedstock suppliers: Feedstock suppliers, including agricultural markets (mandis), traders, and ethanol producers (specifically SAF producers), bridge the gap between raw material sources and biofuel producers by procuring, aggregating, and transporting feedstocks.

Technology, EPC: Technology providers and Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) companies establish and operate efficient ethanol plants. EPC companies manage plant development from design to commissioning, while technology providers offer solutions to enhance production efficiency, reduce costs, and improve sustainability.

Biofuel producers and off-takers: Biofuel producers, encompassing public and private entities, such as grain and sugar industries and oil marketing companies (OMCs), are central to the ecosystem. OMCs, aviation companies, and other sectors integrating biofuels into their operations act as off-takers. OMCs are the primary consumers of bioethanol and biodiesel, blending them with conventional fuels to meet mandated blending targets.

Logistics companies: Logistics companies facilitate the transportation of raw materials, intermediate products, and finished biofuels.

Byproduct off-takers: Byproduct off-takers use the byproducts generated during biofuel production, contributing to economic viability, waste mitigation, and circular economy principles.

Indian companies such as Praj Industries have emerged as key enablers across multiple layers of this ecosystem—from offering advanced fermentation and distillation technologies of first generation(1G) and second generation(2G) ethanol to providing end-to-end Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) solutions for biofuel plants. Their innovation-led approach supports the national agenda of expanding indigenous capacity for biofuel production and reducing import dependence.

Inter-ministerial Coordination: Despite government initiatives to promote biofuel adoption in India, the country needs robust inter-ministerial coordination for cohesive policy formulation by streamlining and demarcating roles and responsibilities across multiple ministries. For example, the Department of Food and Public Distribution (DFPD) takes care of the feedstock-wise allotment of capacity and issuing the Letter of Intent, while the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (MoPNG) deals with the off-taking of biofuels in India. The Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare (MoAFW) oversees feedstock development and propagation. Concurrently, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), oversees the provision of CBG subsidies. Finally, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) is responsible for environmental clearance and carbon credit mechanisms. This distributed responsibility necessitates robust inter-ministerial coordination, with clear and consistent definitions of the specific roles of each stakeholder.

Sugarcane pricing mechanisms, often influenced by Minimum Support Prices (MSPs) for sugar, can create price disparities favouring sugar production over ethanol conversion, impacting feedstock supply for distilleries.

Economic and Regulatory Barriers: The financial incentives for farmers to supply sugarcane to sugar mills rather than ethanol distilleries, combined with the fluctuating availability of critical feedstocks, such as sugarcane and damaged grains, constrain the scalability and economic viability of ethanol production. Sugarcane pricing mechanisms, often influenced by Minimum Support Prices (MSPs) for sugar, can create price disparities favouring sugar production over ethanol conversion, impacting feedstock supply for distilleries. For instance, when sugar prices are high, farmers prefer diverting sugarcane to sugar mills, reducing its availability for ethanol production. The seasonal nature of sugarcane cultivation and susceptibility to weather-related disruptions further contribute to supply inconsistencies. Damaged grain supply, another key feedstock, also varies depending on agricultural output and post-harvest losses.

While the Union government has implemented regulatory mechanisms, including handing OMCs exclusive control of denatured ethanol to streamline distribution and prevent diversion for potable alcohol production, inconsistent state-level implementation creates logistical bottlenecks and delays in ethanol delivery. Such inconsistencies highlight the need for uniform nationwide enforcement to achieve the intended efficiency gains and encourage investments in ethanol production infrastructure.

Focus on Electric Vehicles: India incentivises battery electric vehicles (BEVs) over hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) to proliferate full electrification for sustainable transportation. BEVs are categorised under the lowest Goods and Services Tax (GST) bracket of 5 percent, while HEVs and conventional ICE vehicles are categorised under the 28 percent GST bracket, the highest. State-level incentives, including exemptions or reductions in road taxes and registration fees for BEVs, add to their affordability appeal. For instance, Delhi offers a 100 percent road tax exemption for BEVs. On the other hand, Maharashtra’s EV policy provides incentives of INR 5,000 per kilowatt-hour of battery capacity to buyers of all types of electric vehicles.

India had approximately 6,500 public charging stations, significantly lower than the required infrastructure to support mass BEV adoption, especially in rural areas.

Conversely, HEVs face a considerably higher tax burden of 48 percent with GST and cess, depending on vehicle classification, attracting even higher rates for luxury hybrids. While some states, such as Karnataka have implemented modest concessions like reduced road taxes for strong HEVs, these measures are geographically limited and need nationwide consistency. This policy asymmetry reveals a clear preference for BEVs, potentially overlooking the role of HEVs as a viable transitional technology, particularly in regions where it might take much longer to develop charging infrastructure. As of 2023, India had approximately 6,500 public charging stations, significantly lower than the required infrastructure to support mass BEV adoption, especially in rural areas.

While BEVs have zero tailpipe emissions, HEVs offer immediate reductions in fuel consumption and associated GHG emissions, typically up to 50 percent lower CO2 emissions than comparable ICE vehicles. A more balanced approach to taxation and incentives, recognising the complementary roles of BEVs and HEVs, could accelerate the transition to sustainable mobility and contribute to India’s climate change mitigation commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Addressing the existing bottlenecks in biofuel policy implementation necessitates a multifaceted strategy encompassing regulatory, institutional, economic, and logistical enhancements. Brazil’s approach could serve as a model for producing and adopting biofuels.

Subsidies for abundant and underutilised non-traditional feedstocks, such as agricultural waste and lignocellulosic biomass, and prompt payments to farmers can incentivise their participation in the biofuel supply chain.

By implementing these integrated measures, India can establish a resilient and sustainable biofuel ecosystem, effectively contributing to its energy security objectives and climate change mitigation commitments, including the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement.

Nandan H Dawda is a Fellow with the Urban Studies programme at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dr Nandan H Dawda is a Fellow with the Urban Studies programme at the Observer Research Foundation. He has a bachelor's degree in Civil Engineering and ...

Read More +