Image Source: Getty

Background

The idea conveyed in the term “just transition” is a transition to a fairer and cleaner world. It allows for the perception of an orderly and stable long-term plan for a better world. The term exploits optimism bias, whereby people overestimate the likelihood of good events occurring in the future and underestimate the probability of bad events. The ambiguity in interpreting the term has led to overuse, as it provides a way to address the complex challenge of climate change without getting pinned down on details. The lack of a clear definition of the term “just transition” also allows for flexibility and is useful for appealing to a broad political audience without committing to specific actions on political platforms. A truly just transition should drastically reform capitalism’s institutions and make it fundamentally more equitable. This means a much broader agenda for the climate movement that goes beyond carbon trading, carbon pricing and technocratic discussion of mitigation options.

Redistribution of burden

Three worldviews dominate the debate on climate change. The first is a business-as-usual view that believes that economic growth is essential, and economic growth is not possible without growth in energy supply. The second is a slow descent into a low-carbon world with goals set by a technocratic elite and implemented by a bureaucratic elite. The third world view calls for radical change now, with a reversal of the capitalist system that underpins the world economy along with an end to the use of fossil fuels. The second worldview is the dominant view that underpins approaches of multilateral institutions like the United Nations (UN), through the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The basic premise of those in the second camp is that spending money now to slow future global warming is cost-effective. Some in the extreme end of this camp assume 90–100 percent probability of warming exceeding 2°C and a near-zero time-discount rate, which assigns a large weight to the future benefits of prevented climate damage relative to present mitigation costs. Taking a stubborn stand over the three worldviews, many experts indulge in never-ending debates on what constitutes the appropriate social discount rate they unnecessarily make themselves redundant.

There are two more camps that do not participate in the debate. One is the truly poor—those for whom "life is like a lottery". They lack the interest, organization, and media skills that would give them access to the debate. They have enough on their short-term plate as it is without bothering themselves about energy futures that they cannot see and that they could not do anything about even if they could see them. The other camp deliberately avoids getting sucked into the debate. Their small-scale autonomy is sustained by a voluntary myopia that actively resists the construction of long-time perspectives.

The concept of a “just transition” towards a fair and clean world is part of the third worldview, but the second worldview, controlled by multilateral institutions such as the IPCC, has co-opted the concept of “just transition” to broaden the appeal of its dry technocratic narrative and to dilute the influence of the radical third worldview. The technocratic worldview is likely to be closest to the actual path of the energy transition, but it is unlikely to produce just or equitable outcomes.

The agricultural-to-industrial transition further divided the peasant class into a manufacturing class that produced goods for the warrior and ruling classes, while the peasant class produced surplus food for non-food-producing classes.

Historically, all transitions have created a stratified and unequal world. When hunter-gatherer groups transitioned to agrarian communities, societies were divided into a warrior class that defended territory and a peasant class that worked the land. The agricultural-to-industrial transition further divided the peasant class into a manufacturing class that produced goods for the warrior and ruling classes, while the peasant class produced surplus food for non-food-producing classes. At a broad level, the industrial transition divided the world into countries of agrarian food producers, raw material producers and manufacturers, and a small but affluent and powerful class of countries that controlled the flow of capital and knowledge. The industrial-to-information transition added a superior class of information and intelligence workers above the peasants and proletarians. The ongoing information-to-ecological transition is likely to further stratify the World rather than challenge the capitalist roots of energy and climate injustices.

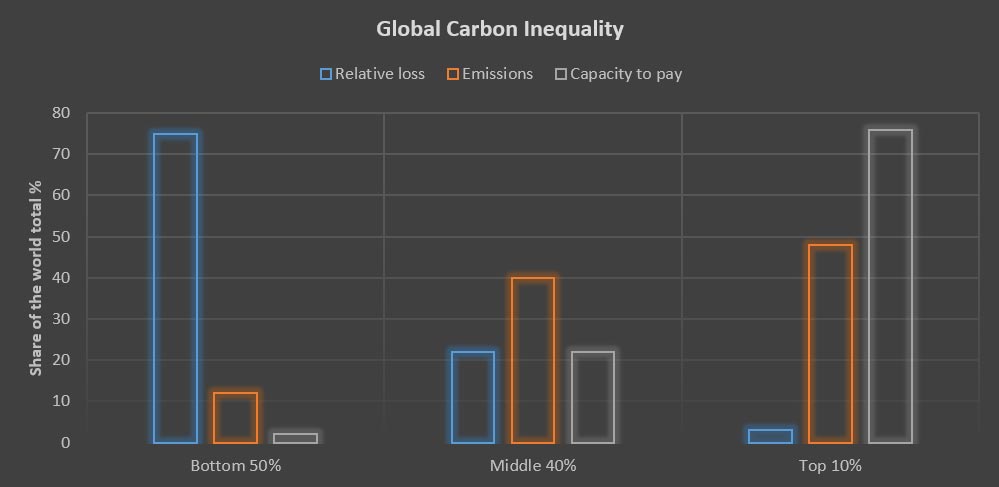

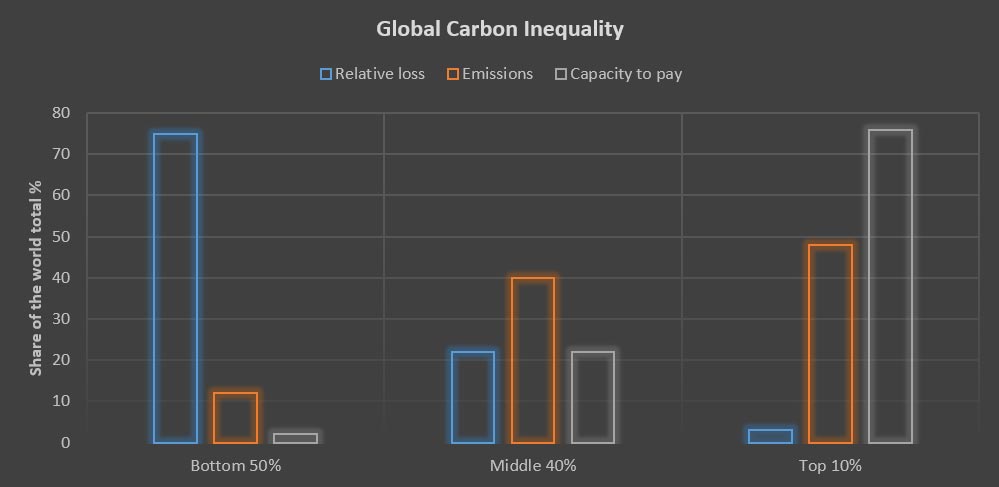

The IPCC’s special report stated that higher 2°C pathways required a carbon tax of US$15–220/tCO2eq (tonnes of carbon-di-oxide equivalent) in 2030 (all in 2010 US$) and US$45–1050/tCO2eq in 2050, while for below 1.5°C pathways the required carbon tax was US$135–6050/tCO2eq in 2030 and US$245–14,300/tCO2eq in 2050. Studies have shown that mitigation policies such as carbon pricing, suggested by the IPCC, could have negative side effects on the global poor. As per the conclusions of one study, at the international level, a uniform carbon price would lead to higher relative policy costs for developing countries. Without compensating measures, mitigation policies could also hamper progress towards universal access to clean energy, thus potentially preventing further development and creating a poverty trap. Similarly, higher food prices caused by land-based mitigation measures could undermine efforts towards a world without hunger. In addition, the study concluded that average per-capita income levels in developing countries would decrease considerably under ambitious mitigation policies. Even under strongly differentiated carbon prices, the international distribution of mitigation costs was found to be regressive. In addition, the increases in energy and particularly food expenditures triggered by carbon pricing were substantial. At the same time, the revenues from carbon pricing were expected to be modest in poor and in developing countries, both due to the low per-person emissions from the energy sector and the initially low carbon price. The key conclusion of the study is that climate policy without progressive redistribution policies would increase the poverty headcount without progressive redistribution.

Another study showed that tightening the carbon pricing regime would lead to a significant increase in energy prices, a persistent fall in emissions, and an uptick in green innovation. This would come at the cost of lower economic activity and higher inflation. Importantly, these costs were borne unequally across society. Poorer households lowered their consumption significantly and drove the aggregate response, while richer households were less affected. Not only were poor households more exposed to carbon pricing because of their higher energy expenditure share, they also experienced a larger fall in their income. These indirect effects via income and employment was quantitatively important. The study concludes that redistributing some of the carbon revenues to the most affected groups can reduce the economic costs of carbon pricing and may help strengthen the public support of the policy.

Issues for thought

Neoliberal visions of the future, using techno-managerial tools and indicator frameworks such as “carbon prices”, “smart infrastructure”, and “innovative financial instruments”, are likely to reproduce the world by other means. Its use of technocratic and bureaucratic rationality erases the complexity of the real world. Under the Coasian (Ronald Coase) perspective embedded in the narrative efficiency and equity can be separated as long as atmospheric property rights are unequivocally and clearly assigned. This conflates real gross domestic product (GDP) or the value of consumption as the social welfare criterion effectively replacing values with carbon prices. Carbon prices are not distributionally neutral and they are not an unbiased reflection of value based on scarcity or internalised external costs but coefficients of power. Markets can deliver efficient outcomes through carbon prices but the question is efficient for whom?

Source: World Inequality Report

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV