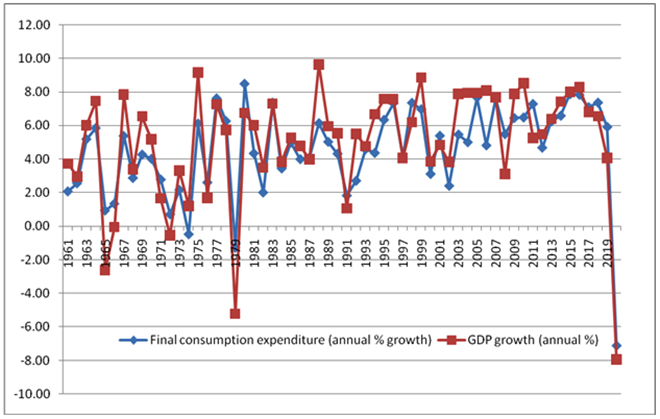

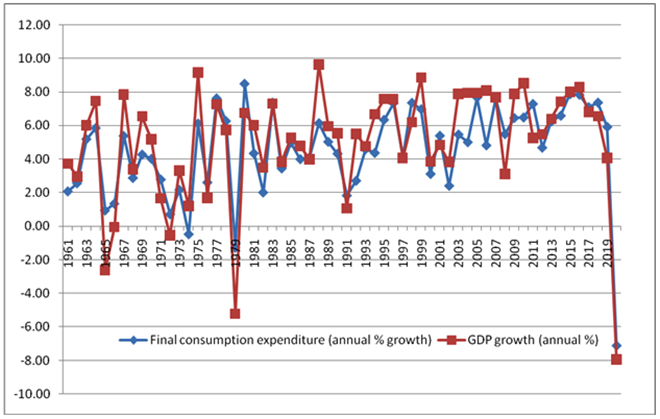

The Indian growth (or the lack of it on recent counts) story over the last three decades has been a consumption-led one. This has been argued time and again in policy circles, in empirical analysis drawing on the causal relation between growth and private consumption, and also in a recent paper by Abhijit Mukhopadhyay of the Observer Research Foundation. On recent counts, the deceleration of the Indian economy, and then negative growth during 2020-21 have been attributed to the decelerating private consumption expenditure growth, and then to lack of consumption demand, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Final Consumption growth and GDP growth (1961 to 2020)

Source: computed from World Bank data (data.worldbank.org)

Source: computed from World Bank data (data.worldbank.org)

As such, the “consumption-led-growth” strategy has often been resorted by many emerging economies as one of the ways to spur investment and production within the economy. For example, China explicitly acknowledged promoting “consumption-led-growth” in their 14th five-year plan through increases in wages and salaries so as to increase purchasing powers of their citizens. This paradigm shift from “export-driven-growth” to "consumption-led growth" was compelled by the global economic slump that mostly affected the US and EU after 2008, thereby, denting demand for Chinese exports. China realised that such unpredictabilities in the external sector emerging from the risks embedded in international trade and finance cannot sustain Chinese growth ambitions. Under such circumstances, China had to resort to boosting domestic consumption demand to provide impetus to their growth. However, for India, the force of consumption demand as a driver of growth emerged organically rather than as a policy intervention. Therefore, though one may talk of the fiscal packages announced in the 2020 pandemic year as the driver of the apparent revival of the Indian economy (as Asian Development Bank (ADB) projects that the Indian growth will be 10 percent in 2021-22), the force of private consumption should not get blurred in the visions of the policymakers. This is especially true for constantly feeding and sustaining economic growth in the medium and long-run.

The story of an “unequal India” is neither simple nor comfortable for New Delhi, being treated as a maverick field of research and a normative concern for policy, thereby, making it lurk somewehere in the background in the development policy discourse. In that sense, inequality, despite being a problematic developmental issue, it hardly got mainstreamed in policymaking, with the concern of high growth taking the limelight

It is here that the story of inequality enters. The story of an “unequal India” is neither simple nor comfortable for New Delhi, being treated as a maverick field of research and a normative concern for policy, thereby, making it lurk somewehere in the background in the development policy discourse. In that sense, inequality, despite being a problematic developmental issue, it hardly got mainstreamed in policymaking, with the concern of high growth taking the limelight. The argument made here is that the increasing inequality is going to be a critical deterrent for long-term growth. The seminal and celebrated paper by Simon Kuznets in the American Economic Review in 1955 exposed the Kuznets phenomenon or the Kuznets’ curve (KC): An inverted-U or bell-shaped relation between economic growth and inequality. This implies that at the initial stages of growth, the economic inequality increases, and it starts declining after growth reaches a threshold. The Kuznets’ hypothesis has not only received empirical support, but also empirical and theoretical dissent, especially from those who began citing the East Asian Miracle in the 1980s. Yet, if the Kuznets’ hypothesis is true, India is still on the rising side of the KC conforming to its “developing nation” status.

Be that as it may, there is no doubt that economic inequality in India is increasing, as evident from the data from World Inequality Database. This is true for both income and wealth inequalities. Rather interestingly, wealth inequality increased at a much faster rate than income inequality, and more importantly, wealth inequality increased at a much faster rate between 1991 and 2020—i.e. in the post-liberalisation phase—as compared to its movement between 1961 and 1991. This is evident from Table 1. While the possession of wealth of the top 1 percent of the population increased from 11.9 percent in 1961 to 16.1 percent in 1991, the same proportion of population owned 42.5 percent of the wealth in 2020. On the other hand, the proportion of wealth of the bottom 50 percent of the population declined from 12.3 percent in 1961 to 2.8 percent in 2020, thereby, indicating on the increasing chasm in wealth possession amongst the population.

| Table 1: Wealth Inequality in India (share of population in total wealth in %) |

| |

Top 1% |

Top 10% |

Middle 40% |

Bottom 50% |

| 1961 |

11.9 |

43.2 |

44.5 |

12.3 |

| 1971 |

11.2 |

42.3 |

46 |

11.8 |

| 1981 |

12.5 |

45 |

44.1 |

10.9 |

| 1991 |

16.1 |

50.5 |

40.7 |

8.8 |

| 2002 |

24.4 |

55.6 |

36.3 |

8.2 |

| 2012 |

30.7 |

62.8 |

30.8 |

6.4 |

| 2020 |

42.5 |

74.3 |

22.9 |

2.8 |

Source:https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/does-india-have-inequality-problem and World Inequality Database (both accessed on October 15, 2021)

On the other hand, though income inequality was initially declining between 1961 and 1991 (as can be made out from Table 2), it started increasing after 1991. Hence, it won’t be incorrect to infer that the liberalisation and the high growth phase of the Indian economy have been associated with increasing income and wealth inequalities.

| Table 2: Income Inequality in India (share of population in total wealth in %) |

|

Top 1% |

Top 10% |

Middle 40% |

Bottom 50% |

| 1961 |

13 |

37.2 |

42.6 |

21.2 |

| 1971 |

11.7 |

34.4 |

44 |

22.8 |

| 1981 |

6.9 |

30.7 |

47.1 |

23.5 |

| 1991 |

10.4 |

34.1 |

44.9 |

22.2 |

| 2002 |

17.1 |

42.1 |

39.2 |

19.7 |

| 2012 |

21.7 |

55 |

30.5 |

15.1 |

| 2019 |

21.7 |

56.1 |

29.7 |

14.7 |

Source:https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/does-india-have-inequality-problem and World Inequality Database (both accessed on October 15, 2021)

Reiterating fig. 1, it can be seen that the periods of high GDP growth rates of the Indian economy converge with periods of high growth in final consumption, especially after 1991. While inequality has also increased after 1991, any further increase in inequality will have serious consequences on promoting and sustaining high growth in the longer run. In order to do that, we go back to the fundamental definitions of income and wealth inequalities. Though income and wealth are related, they are conceptually distinct: Income is the flow of financial resources for an economic entity—household, firms, etc.—from wages and salaries, profits, investments, government transfers, and various other sources in a particular year. On the other hand, wealth is a stock, and is comprised of the entity’s total savings and assets from the past with additions to assets and savings in the present year. In that sense, wealth provides a metric of an entity’s net worth—total assets minus total liabilities. As such, both income and wealth are important for household financial well-being, and holding of wealth helps the households or economic agents to finance their consumption needs even when incomes dry out during economic crisis.

As per table 1, there has been an increase in the total proportion of wealth in the hands of the top 1 percent though the income inequality has not increased by the same proportion. This implies that a large portion of the incomes earned historically by the top 1 percent (or even top 10 percent) have gone into savings or asset creation rather than moving through the consumption route. On the other hand, empirical studies in various parts of the world go on to show that the marginal propensity to consume (or increase in consumption expenditure with a unit increase in income or wealth) of the lower income groups is much higher than the higher income groups. This implies that an increase in income or wealth of the lower income groups has a higher chance of getting into the consumption channel of the economy than an increase in income of the higher income groups (for whom the chances are higher of getting into the savings or asset creation channel). In other words, the phenomenon of “rich getting richer” will go against the fundamental goal of achieving fast yet sustained growth, however communistic the idea might sound!

Hence, the governmental response has to be Keynesian in nature with spurring up of transfers (or providing for basic incomes whether univeral or targeted) in the short run, but also be an enabler of the market forces in the longer run. In a recent article, Maitreesh Ghatak suggests the government to resort to greater wealth taxation and using the money to invest in education, health, and infrastructure to create a robust human capital base for long-term growth. Yet, the governmental interventions into such systems should not be taken as the permanent solution. Rather, the governments need to enable markets to generate forces so as to create jobs and concomitantly create human capital that can live up to the challeges of the future economy. This, therefore, needs a much more integrated approach to the problems of development rather than looking at development through the reductionist lens of economic growth only.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV