The ongoing Qatar diplomatic crisis started on 5 June 2017, when Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain and Egypt cut all political, economic and diplomatic links with the Qatari state. In addition, these countries gave Qatari citizens 14 days to leave their respective territories and banned their own citizens from travelling to or residing in Qatar. Tensions between Saudi Arabia and Qatar, both US allies, were simmering since the Arab Spring. While the former strived to maintain status quo in the region, the latter supported the revolutionary wave. The rivalry between Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shia Iran, with Qatar tilting towards Iran, was also a key factor in contributing to the growing rift. However, the primary reason officially stated for this boycott by the Saudi-led states was Qatar’s alleged support to funding and fostering of terrorism in the region, by supporting organisations like Hezbollah, Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.

The news of this crisis attracted more attention in India than most matters pertaining to foreign policy usually do. The reason for this was not only the proximity of the region and Qatar’s importance as India’s key oil and energy partner, but also due to the vast number of Indian workers in the region. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have the highest ratio of foreign residents in the world, as they comprised 49 percent of the total population on a regional average. In countries like UAE, this figure is as high as 80 per cent. Among foreign residents, Indians are the largest expatriate community working in the private sector, sending home approximately $35 million in remittances every year. In Qatar alone, Indians comprise 30.5 percent of the total population. This explains why the crisis presented a challenge for Indian foreign policy demanding a nuanced approach to migrants in the region.

In order to assess whether India tackled the crisis effectively, it is important to understand its changing relations with the GCC. Engagement with the diaspora has been a key component of Indian diplomacy after India’s 1991 economic reforms, which set in motion a level of migration of Indian workers abroad. While outflow of labour to developed sectors was mostly in skilled sectors such as IT and services, labour migration to the GCC countries comprises over 80 percent of semi-skilled and low-skilled workers. These workers are involved in providing short-term contractual labour, under conditions strictly regulated by the kafala system, which requires all unskilled laborers to have an in-country sponsor, usually their employer, who is responsible for their visa and legal status. This resultant dependence of workers on their sponsors has led to numerous cases of abuse and mistreatment of Indians in the region, frequently highlighted by human rights organisations. However, traditionally, India’s response to crises in the GCC countries has been ad-hoc and driven by short-term concerns. For example, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 led to the evacuation of 150,000 Indians from the country. However, even in that scenario, the MEA initially failed to directly condemn Iraq’s actions and drew criticism from the UN. It was only after the criticism and a change in government, that India supported the UN resolution mandating international intervention if Iraqi troops failed to withdraw from Kuwait by 15 January 1991. In the recent past, although nationalisation programmes started to support the indigenous workforce in the region have led to diminishing returns for migrants, bilateral negotiations between India and the GCC countries have tended to focus more on ensuring continued access to labour markets and uninterrupted flow of remittances than a guarantee for the rights and welfare of migrant workers. Consequently,, both India and the GCC countries have been reluctant to sign the ILO and UN conventions on migrant workers’ rights.

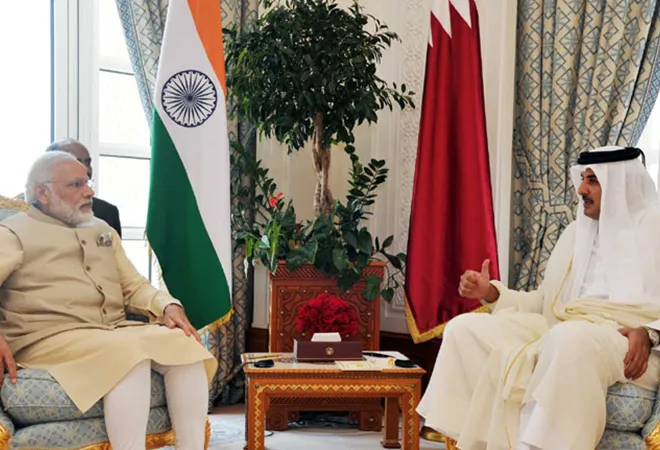

However, with Narendra Modi coming to power in 2014, many expected that the new leadership abroad would deliver real gains in building new avenues of reaching out to the diaspora. The BJP manifesto, for instance, stated, “The NRIs, PIOs and professionals settled abroad are a vast reservoir to articulate the national interests and affairs globally. This resource will be harnessed for strengthening brand India”. In this regard, the decisions to merge the Ministry of Overseas Indians Affairs (MOIA) with Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), establish an Indian Community Welfare Fund in each GCC state and set up Overseas Resource Workers Centres were seen as positive outcomes.

The first real test of this strengthened approach to diaspora diplomacy, however, came in the form of the aforementioned Qatar crisis. The first response to the situation came through External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj, who quickly termed it an “internal matter of GCC” which should be resolved through a process of constructive dialogue and peaceful negotiations. The MEA’s response focused on enabling smooth travel for Indians living in the country, and additional flights were operated by Air India and Jet Airways to bring Indian nationals back to India. On 22 June, a statement from the MEA stated that Indians in the region were safe and secure and thus there was no need for evacuation. Subsequently, an “Indian-Qatar Express Service” was launched for the shipment of food products and other essentials from India. In return, during a delegation level meeting held in August, Qatar's Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed Bin assured India that “jobs will not be politicised”. As a welcome measure, Qatar allowed Indians, along with nationals of 46 other countries, to stay up to 60 days in Qatar without getting a prior visa.

In essence, the response mirrored the ad-hoc and temporary nature of India’s approach to migrants in the region, as was the case during the 1990 Kuwait invasion. The interests of Indian migrants in Qatar were seemingly addressed without antagonising the other powers in the region. However, the opportunity to formulate a comprehensive and longer-term policy for protecting the rights of workers in the GCC countries was lost. As international media has reported, the crisis has made life harder for foreign workers in Qatar, who were already facing lay-offs caused by low oil prices and a work-sponsorship system that is becoming more rigid with every passing day. Rising prices of basic necessities like food and oil has led to increasing indebtedness amongst the low skilled migrant workers. Further, Human Rights Watch (HRW) also pointed out that a number of workers have been instructed to take extended unpaid leave and return to their countries because of a drop in job vacancies caused by the embargo. These concerns of the workers remain unaddressed by the Indian foreign policy establishment. Although remaining neutral in the crisis was the right choice for New Delhi, it lost an opportunity to address the concerns and interests of the diaspora.

Shruti Sonal is a Research Intern at Observer Research Foundation, Delhi

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

The ongoing Qatar diplomatic crisis started on 5 June 2017, when Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain and Egypt cut all political, economic and diplomatic links with the Qatari state. In addition, these countries gave Qatari citizens 14 days to leave their respective territories and banned their own citizens from travelling to or residing in Qatar. Tensions between Saudi Arabia and Qatar, both US allies, were simmering since the Arab Spring. While the former strived to maintain status quo in the region, the latter supported the revolutionary wave. The rivalry between Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shia Iran, with Qatar tilting towards Iran, was also a key factor in contributing to the growing rift. However, the primary reason officially stated for this boycott by the Saudi-led states was Qatar’s alleged support to funding and fostering of terrorism in the region, by supporting organisations like Hezbollah, Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.

The news of this crisis attracted more attention in India than most matters pertaining to foreign policy usually do. The reason for this was not only the proximity of the region and Qatar’s importance as India’s key oil and energy partner, but also due to the vast number of Indian workers in the region. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have the highest ratio of foreign residents in the world, as they comprised 49 percent of the total population on a regional average. In countries like UAE, this figure is as high as 80 per cent. Among foreign residents, Indians are the largest expatriate community working in the private sector, sending home approximately $35 million in remittances every year. In Qatar alone, Indians comprise 30.5 percent of the total population. This explains why the crisis presented a challenge for Indian foreign policy demanding a nuanced approach to migrants in the region.

In order to assess whether India tackled the crisis effectively, it is important to understand its changing relations with the GCC. Engagement with the diaspora has been a key component of Indian diplomacy after India’s 1991 economic reforms, which set in motion a level of migration of Indian workers abroad. While outflow of labour to developed sectors was mostly in skilled sectors such as IT and services, labour migration to the GCC countries comprises over 80 percent of semi-skilled and low-skilled workers. These workers are involved in providing short-term contractual labour, under conditions strictly regulated by the kafala system, which requires all unskilled laborers to have an in-country sponsor, usually their employer, who is responsible for their visa and legal status. This resultant dependence of workers on their sponsors has led to numerous cases of abuse and mistreatment of Indians in the region, frequently highlighted by human rights organisations. However, traditionally, India’s response to crises in the GCC countries has been ad-hoc and driven by short-term concerns. For example, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 led to the evacuation of 150,000 Indians from the country. However, even in that scenario, the MEA initially failed to directly condemn Iraq’s actions and drew criticism from the UN. It was only after the criticism and a change in government, that India supported the UN resolution mandating international intervention if Iraqi troops failed to withdraw from Kuwait by 15 January 1991. In the recent past, although nationalisation programmes started to support the indigenous workforce in the region have led to diminishing returns for migrants, bilateral negotiations between India and the GCC countries have tended to focus more on ensuring continued access to labour markets and uninterrupted flow of remittances than a guarantee for the rights and welfare of migrant workers. Consequently,, both India and the GCC countries have been reluctant to sign the ILO and UN conventions on migrant workers’ rights.

However, with Narendra Modi coming to power in 2014, many expected that the new leadership abroad would deliver real gains in building new avenues of reaching out to the diaspora. The BJP manifesto, for instance, stated, “The NRIs, PIOs and professionals settled abroad are a vast reservoir to articulate the national interests and affairs globally. This resource will be harnessed for strengthening brand India”. In this regard, the decisions to merge the Ministry of Overseas Indians Affairs (MOIA) with Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), establish an Indian Community Welfare Fund in each GCC state and set up Overseas Resource Workers Centres were seen as positive outcomes.

The first real test of this strengthened approach to diaspora diplomacy, however, came in the form of the aforementioned Qatar crisis. The first response to the situation came through External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj, who quickly termed it an “internal matter of GCC” which should be resolved through a process of constructive dialogue and peaceful negotiations. The MEA’s response focused on enabling smooth travel for Indians living in the country, and additional flights were operated by Air India and Jet Airways to bring Indian nationals back to India. On 22 June, a statement from the MEA stated that Indians in the region were safe and secure and thus there was no need for evacuation. Subsequently, an “Indian-Qatar Express Service” was launched for the shipment of food products and other essentials from India. In return, during a delegation level meeting held in August, Qatar's Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed Bin assured India that “jobs will not be politicised”. As a welcome measure, Qatar allowed Indians, along with nationals of 46 other countries, to stay up to 60 days in Qatar without getting a prior visa.

In essence, the response mirrored the ad-hoc and temporary nature of India’s approach to migrants in the region, as was the case during the 1990 Kuwait invasion. The interests of Indian migrants in Qatar were seemingly addressed without antagonising the other powers in the region. However, the opportunity to formulate a comprehensive and longer-term policy for protecting the rights of workers in the GCC countries was lost. As international media has reported, the crisis has made life harder for foreign workers in Qatar, who were already facing lay-offs caused by low oil prices and a work-sponsorship system that is becoming more rigid with every passing day. Rising prices of basic necessities like food and oil has led to increasing indebtedness amongst the low skilled migrant workers. Further, Human Rights Watch (HRW) also pointed out that a number of workers have been instructed to take extended unpaid leave and return to their countries because of a drop in job vacancies caused by the embargo. These concerns of the workers remain unaddressed by the Indian foreign policy establishment. Although remaining neutral in the crisis was the right choice for New Delhi, it lost an opportunity to address the concerns and interests of the diaspora.

The ongoing Qatar diplomatic crisis started on 5 June 2017, when Saudi Arabia, UAE, Bahrain and Egypt cut all political, economic and diplomatic links with the Qatari state. In addition, these countries gave Qatari citizens 14 days to leave their respective territories and banned their own citizens from travelling to or residing in Qatar. Tensions between Saudi Arabia and Qatar, both US allies, were simmering since the Arab Spring. While the former strived to maintain status quo in the region, the latter supported the revolutionary wave. The rivalry between Sunni Saudi Arabia and Shia Iran, with Qatar tilting towards Iran, was also a key factor in contributing to the growing rift. However, the primary reason officially stated for this boycott by the Saudi-led states was Qatar’s alleged support to funding and fostering of terrorism in the region, by supporting organisations like Hezbollah, Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.

The news of this crisis attracted more attention in India than most matters pertaining to foreign policy usually do. The reason for this was not only the proximity of the region and Qatar’s importance as India’s key oil and energy partner, but also due to the vast number of Indian workers in the region. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have the highest ratio of foreign residents in the world, as they comprised 49 percent of the total population on a regional average. In countries like UAE, this figure is as high as 80 per cent. Among foreign residents, Indians are the largest expatriate community working in the private sector, sending home approximately $35 million in remittances every year. In Qatar alone, Indians comprise 30.5 percent of the total population. This explains why the crisis presented a challenge for Indian foreign policy demanding a nuanced approach to migrants in the region.

In order to assess whether India tackled the crisis effectively, it is important to understand its changing relations with the GCC. Engagement with the diaspora has been a key component of Indian diplomacy after India’s 1991 economic reforms, which set in motion a level of migration of Indian workers abroad. While outflow of labour to developed sectors was mostly in skilled sectors such as IT and services, labour migration to the GCC countries comprises over 80 percent of semi-skilled and low-skilled workers. These workers are involved in providing short-term contractual labour, under conditions strictly regulated by the kafala system, which requires all unskilled laborers to have an in-country sponsor, usually their employer, who is responsible for their visa and legal status. This resultant dependence of workers on their sponsors has led to numerous cases of abuse and mistreatment of Indians in the region, frequently highlighted by human rights organisations. However, traditionally, India’s response to crises in the GCC countries has been ad-hoc and driven by short-term concerns. For example, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 led to the evacuation of 150,000 Indians from the country. However, even in that scenario, the MEA initially failed to directly condemn Iraq’s actions and drew criticism from the UN. It was only after the criticism and a change in government, that India supported the UN resolution mandating international intervention if Iraqi troops failed to withdraw from Kuwait by 15 January 1991. In the recent past, although nationalisation programmes started to support the indigenous workforce in the region have led to diminishing returns for migrants, bilateral negotiations between India and the GCC countries have tended to focus more on ensuring continued access to labour markets and uninterrupted flow of remittances than a guarantee for the rights and welfare of migrant workers. Consequently,, both India and the GCC countries have been reluctant to sign the ILO and UN conventions on migrant workers’ rights.

However, with Narendra Modi coming to power in 2014, many expected that the new leadership abroad would deliver real gains in building new avenues of reaching out to the diaspora. The BJP manifesto, for instance, stated, “The NRIs, PIOs and professionals settled abroad are a vast reservoir to articulate the national interests and affairs globally. This resource will be harnessed for strengthening brand India”. In this regard, the decisions to merge the Ministry of Overseas Indians Affairs (MOIA) with Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), establish an Indian Community Welfare Fund in each GCC state and set up Overseas Resource Workers Centres were seen as positive outcomes.

The first real test of this strengthened approach to diaspora diplomacy, however, came in the form of the aforementioned Qatar crisis. The first response to the situation came through External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj, who quickly termed it an “internal matter of GCC” which should be resolved through a process of constructive dialogue and peaceful negotiations. The MEA’s response focused on enabling smooth travel for Indians living in the country, and additional flights were operated by Air India and Jet Airways to bring Indian nationals back to India. On 22 June, a statement from the MEA stated that Indians in the region were safe and secure and thus there was no need for evacuation. Subsequently, an “Indian-Qatar Express Service” was launched for the shipment of food products and other essentials from India. In return, during a delegation level meeting held in August, Qatar's Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed Bin assured India that “jobs will not be politicised”. As a welcome measure, Qatar allowed Indians, along with nationals of 46 other countries, to stay up to 60 days in Qatar without getting a prior visa.

In essence, the response mirrored the ad-hoc and temporary nature of India’s approach to migrants in the region, as was the case during the 1990 Kuwait invasion. The interests of Indian migrants in Qatar were seemingly addressed without antagonising the other powers in the region. However, the opportunity to formulate a comprehensive and longer-term policy for protecting the rights of workers in the GCC countries was lost. As international media has reported, the crisis has made life harder for foreign workers in Qatar, who were already facing lay-offs caused by low oil prices and a work-sponsorship system that is becoming more rigid with every passing day. Rising prices of basic necessities like food and oil has led to increasing indebtedness amongst the low skilled migrant workers. Further, Human Rights Watch (HRW) also pointed out that a number of workers have been instructed to take extended unpaid leave and return to their countries because of a drop in job vacancies caused by the embargo. These concerns of the workers remain unaddressed by the Indian foreign policy establishment. Although remaining neutral in the crisis was the right choice for New Delhi, it lost an opportunity to address the concerns and interests of the diaspora.

PREV

PREV