Rural India is home to about 889 million (The World Bank, As on April 2019) who are majorly dependent on the rural health care system. The three tier structure of the rural health care system is based on population norms. Sub-Centres (SC) are the first contact point with the community. Primary Health Centres (PHC) and Community Health Centres (CHC) form the second and third tier of the structure. These PHCs and CHCs play a major role in immunization, labour & deliveries and antenatal & neonatal care. There are approximately 29,000 PHCs and 5,500 CHCs in India.

Government data shows that 6,19,289 villages have now been electrified (Ministry of Power, As on April 2019). However, this may or may not include electricity connection to the health centre. The supply of electricity is irregular mainly in the energy access deprived states (like Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha, West Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, Assam and other North Eastern states). Few of the PHCs/CHCs located in remote areas like riverine PHCs in Assam still await conventional electricity connections. Mere electricity connection is not enough. Almost 20 hours of power supply is required for the Ice Lined Refrigerators (ILR) and deep freezers to store immunization kits. For safe deliveries and neonatal care, equipment such as sterilizers, baby warmers/incubators, lights & fans, are essential. Absence of reliable and quality electricity adversely impacts the overall service delivery of the health centres even if the medical equipment and staff are available adequately.

Absence of reliable and quality electricity adversely impacts the overall service delivery of the health centres even if the medical equipment and staff are available adequately.

In general, diesel generators are provided to PHCs and CHCs for power backup. The operational hours of these generators are restricted due to inadequacy of funds for diesel<1>. In addition, sometimes in remote locations, the supply of diesel is interrupted during monsoons or bad weather. Again, diesel is not a clean energy source. The other option is introduction of off-grid solar photovoltaic (PV) power plants. These plants can be integrated with the conventional electricity system in case of electrified PHCs/CHCs.

Diesel is not a clean energy source. The other option is introduction of off-grid solar photovoltaic (PV) power plants. These plants can be integrated with the conventional electricity system in case of electrified PHCs/CHCs.

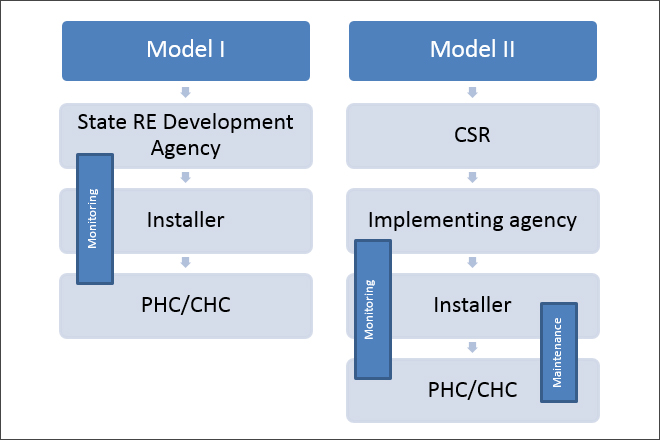

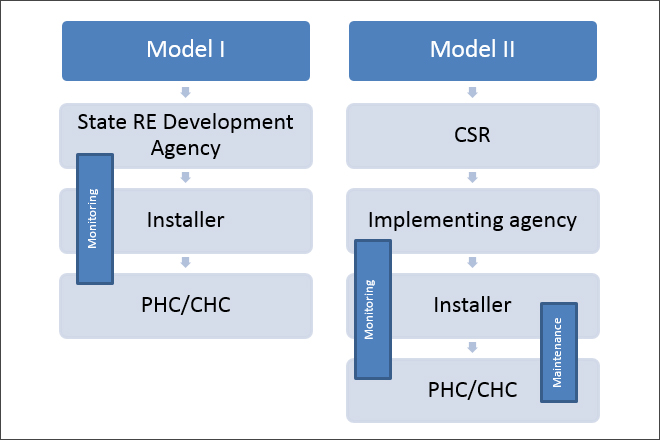

The Chhattisgarh Renewable Energy Development Agency (CREDA) has installed off-grid solar PV power plants in 900 rural health centres with a cumulative capacity of 3 MW (an average of 3.3 kW per centre) (Ashden, As on April 2019). CREDA monitors these systems and maintains them through five year maintenance contract with the installation companies. Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) after conducting an independent evaluation of 147 PHCs in Chhattisgarh reported that solar-powered PHCs showed a 59 per cent increase in outpatient services, 78 per cent increase in deliveries and 45 per cent improvements in laboratory services after installation (CEEW, as on April 2019)).

There is another institutional model also - installation of off-grid solar PV power plants using corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds. The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) with support from Power Finance Corporation (PFC) has installed off-grid solar PV plants in about 57 PHCs/CHCs across the states of Jammu & Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh and Assam. Both the institutional models are recommendable. In general, 5 kW capacity off-grid solar PV power plants are recommended by CEEW (CEEW, As on April 2019) and TERI (TERI, 2017) for PHCs/CHCs to operate basic equipment (required for neonatal care, cold chain points, labour and delivery room, OT room, nursery and women’s ward) at least for 5-6 hours a day. The cost of 5 kW capacity of off-grid solar PV power plant ranges between INR 0.4 and 0.6 million (including installation cost).

There is another institutional model also - installation of off-grid solar PV power plants using corporate social responsibility (CSR) funds.

Considering the benefits of off-grid solar PV plants on overall functionality of the rural health system, it would be worthwhile if other states also take up such initiatives at PHCs and CHCs in areas where availability of reliable electricity is an issue. However, the initial cost for a state to provide solar power plants to all PHCs/CHCs may be high. In such case, the option of full or partial funding from CSR funds and other grants may also be explored. The institutional models may be state specific. The figure below presents the institutional models as discussed above.

Figure 1 Institutional models for Off-grid Solar PV Power PLANTS IN phcs/chcs (Source: Author)

Figure 1 Institutional models for Off-grid Solar PV Power PLANTS IN phcs/chcs (Source: Author)

There is thus a case for taking up similar projects across other states. Under this scenario, the number of stakeholders in the above mentioned institutional models will increase substantially.

Considering the benefits of off-grid solar PV plants on overall functionality of the rural health system, it would be worthwhile if other states also take up such initiatives at PHCs and CHCs in areas where availability of reliable electricity is an issue.

Well defined central and state policies exist for off-grid and grid interactive solar power plants in general but no such policy or guiding document exists for installation and maintenance of off-grid solar PV power plants for rural health centres. Although the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) and state guidelines for procurement and installation may be followed to an extent, but maintenance of these off-grid solar PV power plants for PHCs/CHCs remains with the decision of state level National Health Mission (NHM) offices or health departments or medical officers in PHCs/CHCs. In such a scenario, the availability of a well-defined guiding document for the stakeholders on procurement, installation and especially for maintenance of the off-grid solar PV power plants would be very useful for the PHCs and CHCs.

Well defined central and state policies exist for off-grid and grid interactive solar power plants in general but no such policy or guiding document exists for installation and maintenance of off-grid solar PV power plants for rural health centres.

There are other issues to be addressed as well. PHCs, especially in low population density states, are located mostly at remote locations. The maintenance of these plants somehow depends on the installers mostly through Annual Maintenance Contracts (AMC). Maintenance of off-grid solar PV power plants has to be strengthened through a credible system of maintenance services and monitoring of performance. A solar power plant in general has a life of around 20 years. Only proper maintenance of the systems around its operational life will be able to make the investment a viable option.

Off-grid solar PV power plants for PHCs/CHCs are a viable option as a technology. Expanding this initiative to all the states of India will certainly improve overall functionality of the rural health systems. However, a well-defined guideline on installation and maintenance for NHMs, state health departments, installers and PHCs/CHCs at central and state level would assist in reaping the benefits of off-grid solar power plants for delivery of health services.

References:

Ashden. Accessed on April 2019. https://www.ashden.org/winners/creda#continue.

Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW). August 2017, accessed on April 2019. https://www.ceew.in/publications/powering-primary-healthcare-through-solar-india.

Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW). July 2018, accessed on April 2019. https://www.ceew.in/publications/solar-powered-healthcare-developing-countries.

Ministry of Power. Accessed on April 2019. https://saubhagya.gov.in/.

The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI). 2017, April-May. Clean and Reliable Power for Primary Health Centres in India. eNREE, pp. 12-14.

The World Bank. Accessed on April 2019. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.

<1> Based on author’s interaction with PHCs/CHCs

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Figure 1 Institutional models for Off-grid Solar PV Power PLANTS IN phcs/chcs (Source: Author)

Figure 1 Institutional models for Off-grid Solar PV Power PLANTS IN phcs/chcs (Source: Author) PREV

PREV