Backgrounds

The Government of India (GOI) has a long list of achievements in the energy sector. In the context of the coal sector, one of the achievements listed is the increase in coal quality. According to the statement of the GOI, there has been a substantial improvement in conformity to the declared grade of coal supply from Coal India Limited (CIL) and grade conformity has increased from 51 percent in 2017-18 to 69 percent in 2022-23. The improvement in the quality of coal is attributed to the introduction of improved mining technology like surface miners, supply of washed coal, first-mile connectivity for direct conveying of coal on the belt from coal surface/face to rapid loading silo and the installation of auto analysers. The statements of the GOI also notes that all consumers of CIL have the option of quality assessment of the supplies through independent third-party sampling agencies (TPSA). TPSAs ascertain coal quality from loaded coal wagons/lorries as per prescribed norms under BIS (Bureau of Indian Standards) specifications. Apart from the Central Institute of Mining & Fuel Research (CIMFR) and the Quality Council of India (QCI) two more private agencies provide choices for assessing coal quality. The cost of sampling is shared equally by the coal supplier and the TPSA.

In theory, improvement in coal quality should improve efficiency in coal combustion and reduce negative externalities such as pollution. But in practice, accommodation of a variety of technical trade-offs, and economic and political compulsions compromise the pursuit of environmental goals.

Quality of Indian coal

With Indian coal, there are two broad concerns over coal quality. The first is the concern over consistency in physical quality such as size and the second is the concern over chemical quality. Both concerns may be addressed by coal beneficiation methods that are interrelated. Beneficiation may be carried out at the mining stage to eliminate stone and shale bands and also by selective mining. Beneficiation can also be continued at the post-mining stage through separation of stones, crushing, screening, etc. followed by coal washing. The efficiency of beneficiation to improve chemical composition depends on liberation of inert matter which in turn depends on physical quality as it varies with size ranges of coal. In the case of Indian coal, the liberation of inert matter such as ash is not straightforward.

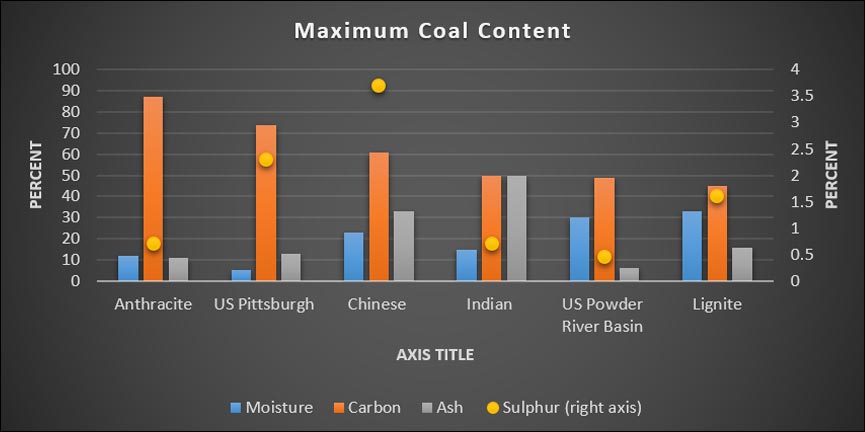

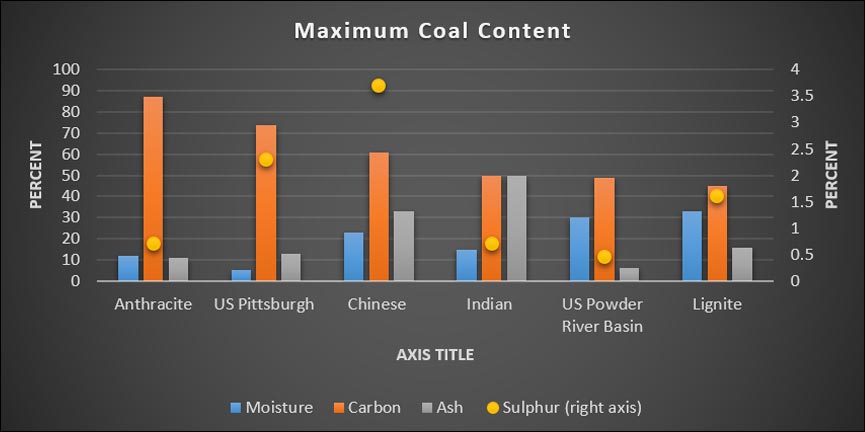

Indian coal is of Gondwana origin and is heterogeneous. These coal deposits are thought to have been transported by water across long distances carrying impurities after which coalification is said to have taken place. Such coals are said to be of ‘drift origin’ and have mineral matter finely disseminated with coal matter causing significant deterioration in quality in the formation stage itself. The mineral matter of which ash is a major part is inherent ash (as opposed to free ash) embedded in the combustible part of the coal and therefore cannot be easily removed. More than 75 percent of Indian coal has ash content of more than 30 percent or higher with some where the ash content is as high as 50 percent. This is high compared to coal traded on the international market where ash share rarely exceeds 15 percent.

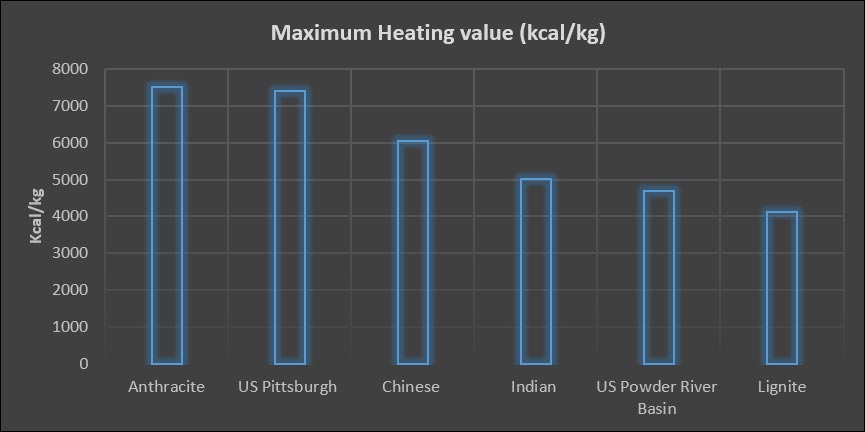

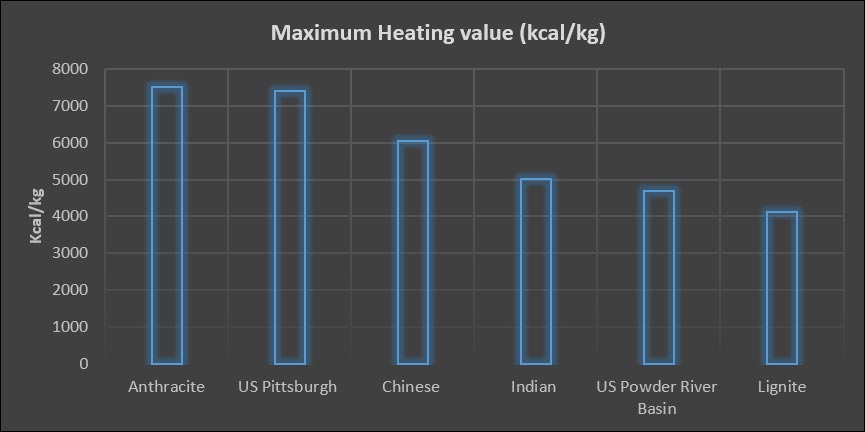

High ash content is among reasons why Indian coal scores poorly on energy content. Most of the coal produced in India is in the range of 3,500–5,000 kcal/kg (kilo calories per kilogram) which is lower than the calorific value of coal found in major countries such as the US, Russia and China. India’s rank as the world’s third largest coal producer reported in volume terms drops to the fifth place after China, US, Indonesia and Australia when reported in energy terms.

Source: The Future of Coal, MIT

The intrinsic quality of Indian coal along with the dominant practice of open-cast mining has meant that (Run of the Mine) ROM Indian non-coking coal contains a high share of ash and other minerals. ROM coal typically has a high ash content of 30-50 percent and low calorific value (2500-5000 kilocalories per kilogramme—kcal/kg). In general, high ash content creates problems for coal users that include but are not limited to erosion, difficulty in pulverisation, poor emissivity and flame temperature, low radiative transfer, and generation of excessive amounts of fly ash containing large amounts of unburnt carbon. In addition, the transport of ROM coal across long distances is wasteful as it carries large quantities of ash-forming minerals that results in shortages of rail and port capacity. The transport of high ash coal across long distances also contributes to the emission of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHG) from the mode of transport (rail and road).

The average gross calorific value (GCV) of coal supplied to power plants in India declined from about 5,900 kcal/kg in the 1950s to just over 3,500 kcal/kg in the 2000s. Since the 2000s production of high and mid-energy coal (more than 4,200 kcal/Kg) has stagnated in India while the production of low-energy coal (less than 4200 kcal/kg) has more than doubled. This means that 1.5 tonnes of Indian coal have to be mined to get the same energy content of 1 tonne of Australian coal. Some improvement in the quality of coal mining in India is expected by 2040 on account of a marginal increase in the share of coal from under-ground mines but coal quality is assumed to remain a problem for India in the next two decades. The focus on ‘easy-to-mine’ coal from shallower depths that contributed to the decline in coal quality is expected to sustain the trend of decreasing energy content per tonne of coal production in India.

Theory

In theory, upgrading coal quality (beneficiation) is expected to offer benefits at two levels. One is the possible short-term benefit of reduction in polluting emissions that result from using upgraded coals in existing power plant boilers. The other is the longer-term benefit arising from the use of advanced clean coal technologies which may demand the use of upgraded coal by design in order to realize their potential for increased thermal efficiency. There are other process implications of coal upgrading, but they are mainly second-order effects. For example, reducing the ash content of coal may make it easier to grind, so that the energy used in the mills is reduced. The amount of pyrite present is also likely to be reduced in washed coal.

Beneficiation is also expected to improve overall plant operations that directly affect the profitability of a coal plant over the long term and also improve its ability to avoid environmental penalties and disputes. It could also potentially improve the life of emission control devices. Most of the ash present in coal travels through the combustion process and is captured by emission control devices such as electrostatic precipitators. Washed coal use reduces the amount of ash produced and collected by these devices and extends their useful lives. Power plants that use coal of higher quality have a performance advantage over lower-quality coal. In general, higher the ash content of coal, lower is the heating value of coal per unit weight of coal. When the percentage of ash content is reduced, the heating value of coal is increased and so less coal can be burnt to produce a given quality of electricity. When low-ash coal is used, plant operators can reduce scheduled and unscheduled maintenance required to remove ash collection. Lower ash coal can also reduce corrosion on plant ductwork which reduces plant life. If power-generating plants that are designed to burn one type of coal, then they must continue to be supplied with a similar coal or undergo an extensive and costly redesign in order to adapt to a different type of coal.

Low ash coal can potentially reduce damage to all coal handling equipment such as such as conveyors, pulverisers, crushers and storage. The use of higher ash coals increases load on the plant that increases the quantity of plant site energy needed to operate the plant which reduces the energy available for power generation. This increases plant operating costs and decreases its profit potential.

Main emissions from coal and lignite-based thermal power plants in India are CO2, Oxides of Nitrogen (NOX) and oxides of sulphur (SOX) and air-borne inorganic particles such as fly ash, carbonaceous material (soot), suspended particulate matter (SPM) and other trace gas species. Thermal power plants are among the large point sources (LPS) accounting for 50 percent of CO2 and SOX and about 20 percent of NOX. Coal beneficiation has the potential to reduce the level of these emissions.

Practice

Until 2020, government policies favoured the beneficiation of coal. In 1988, the Planning Commission constituted the Ronghe Committee to study the issue of washing coal. The committee came to the conclusion that washing would be cost-effective only if coal is transported over a distance of 1,000 km (kilometres) when the cost of beneficiation would more or less get neutralised by saving in the cost of transportation of additional ash in coal. Coal washing was opened to the private sector but the 10th plan (2002-2007) noted that the results were mixed and concluded that ‘washeries were uneconomical’ and that there were no takers. The 11th plan (2007-12) identified coal beneficiation as one of the prime clean coal technologies. It observed that coal washing would ensure consistent fuel supply to conventional Pulverised Coal Combustion (PCC) boilers and improve efficiency by 1 percent. It further noted that ‘perfect’ growth on coal washing would be realised if the suggestion to price coal on a fully variable gross calorific value Basis (GCV) was implemented as it would provide the right incentive to both the producer and consumer to improve the quality of coal. It cautioned that an increase in washing capacity would consequently increase the demand for raw coal unless fines were used productively. In the early 2000s, some of the coking coal washeries converted to non-coking coal washeries anticipating the enforcement of the Ministry of Environment & Forests (MOEF&CC) directive notified in 1998 mandating the use of coal containing not more than 34 percent ash in power stations located 1,000 km from pitheads and those located in urban/sensitive/critically polluted areas effective from June 2001. In addition, all new coal plants were mandated to use supercritical technology and existing plants were assigned mandatory efficiency targets which will require use of higher quality coal.

In 2020 the government rolled back the directive on transport of unwashed coal. The revised directive stated that the Ministry of Power had argued against coal washing on the basis of the following outcomes (i) washing of coal reduces ash content only marginally (ii) washery rejects find their way into the market for use in industries that cause pollution (iii) high cost of washing, cost transport of unwashed & washed coal and the cost of loading and unloading coal that result in higher power tariff (iv) pollution caused by the process of washing (v) competition from imported coal especially in the case of coastal power plants (vi) loss of calorific value in washing (vii) advance in technologies that allow pollution control at the smoke stack. For its part the Ministry of Coal (MOC) has also submitted that (i) the quality of raw coal supply had improved substantially (ii) use of raw coal reduces energy charge rate (ii) use of super critical technology can use unwashed coal efficiently (iii) washing localises pollution. In addition, the MOEF&CC also cited a NITI Aayog report commissioned for the purpose that reiterated most of the observations of the MOC and the Ministry of Power (MOP) with the additional comments that (i) environmental benefit of washing is marginal (ii) ash generated by power plants is more useful than ash generated by coal washeries (iii) no environmental rationale for fixing 500 km limit for using unwashed coal (iv) the 500 km limit offers undue price advantage for power plants that are within the limit.

Questions for thought

One of the most important but not explicitly stated messages in the observations of the MOC, MOP, NITI Aayog and the MOEF&CC is that the costs of improving the quality of coal cannot be passed on to the consumer (electricity ratepayer). This highlights one of the dilemmas of producing environmental goods such as clean air in India. The use of higher quality coal produces an environmental public good in the longer term while the costs are immediate and private. This raises an important question: Should the cost of increasing coal quality be publicly funded?

Another issue that may be debated in the context of the changing narratives over cleaning coal is whether there are interests other than efficiency and environmental sustainability in increasing the quality of coal. When MOEF&CC was in favour of regulating the production of clean coal, there was a thrust on imported coal from newly constructed private power generators. Mandating the use of clean coal served the interests of importers. It also served the interests of private washeries that could potentially divert coal supply to users that did not have formal coal supply linkages with CIL. The position has now reversed. Pollution control technologies have shifted from mines to power plants. Though self-reliance and energy security have become dominant interests subordinating environmental concerns, the commercial interests of all players in the value chain have also contributed to changing the dominant narrative on cleaning coal.

Source: The Future of Coal, MIT

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Akhilesh Sati is a Program Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

Vinod Kumar Tomar is a Assistant Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV