The domain of warfare is constantly evolving thanks to technological innovation. Emerging technologies like Artificial Intelligence (AI) and drones are playing an increasingly dominant role in dictating the tenets of war in the current age. The war in Ukraine, the Israel-Hamas War, and the Red Sea Crisis are all testaments to the increasingly pervading influence of these technologies on the battlefield. A particularly interesting example of this is the growing proliferation of hypersonic weapons. With Russia employing their use on at least three occasions in the Ukraine War, and both Yemen’s Houthis and North Korea claiming to have successfully tested them recently, hypersonic weapons may have a critical role to play in future warfare.

What are hypersonic weapons?

A hypersonic weapon refers to one which travels faster than Mach 5, or five times the speed of sound (330 m/s). There are two types: Hypersonic glide vehicles (HGV) are launched from a rocket, similar to regular ballistic missiles, before gliding to a target, whereas Hypersonic cruise missiles are powered throughout their flight via air-breathing engines called Scramjets, after acquiring their target.

With Russia employing their use on at least three occasions in the Ukraine War, and both Yemen’s Houthis and North Korea claiming to have successfully tested them recently, hypersonic weapons may have a critical role to play in future warfare.

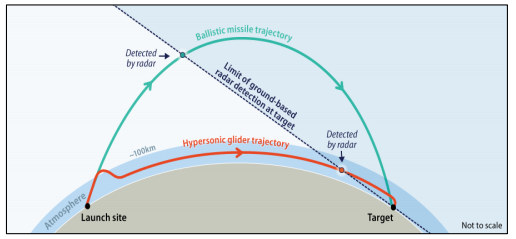

Hypersonic weapons have been in existence since the middle of the 20th century. Ballistic missiles, for instance, have long possessed these speeds. What differentiates today’s hypersonic capabilities is that, unlike ballistic missiles, HGVs do not follow a parabolic trajectory to their target, making their re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere much quicker and at a much lower altitude. They can subsequently glide to their target while executing advanced evasive manoeuvres under guided flight. Additionally, HGVs can have ranges up to thousands of kilometres, effectively making them equivalent to intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). Hypersonic cruise missiles fly at considerably lower altitudes, typically around 200 feet above the ground, and also possess enhanced manoeuvrability and speed. Consequently, hypersonic weapons can bypass most traditional defence systems, and their detection poses a serious challenge. For example, terrestrial-based radar cannot detect them until late in their flight. The threat is only bolstered by the fact that they are capable of carrying both traditional and nuclear warheads.

Source: The Economist

Global initiatives and progress

Though several countries including Australia, India, France, Germany, South Korea, North Korea and Japan, are actively developing hypersonic weapon technology, the United States (US), China and Russia have made the most progress thus far. The primary reason for this, particularly in the case of China and Russia, seems to emanate from the US withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2001, and the growing concern that the US can simply intercept any missiles launched at them.

United States

|

Programme

|

Department

|

Details

|

|

Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS)

|

US Navy

|

The US Navy’s CPS programme is the foremost and most heavily funded hypersonic weapons initiative. The first test conducted under it in June 2022 failed, while two subsequent tests scheduled for 2023 were cancelled due to failed preflight checks. However, the Navy plans to deploy CPS on certain submarines and destroyers as early as 2025.

|

|

Hypersonic Air-Launched OASuW (HALO)

|

US Navy

|

The US Navy also initiated the HALO programme in 2023, which is likely to be compatible with its F/A- 18 fighter jet.

|

|

AGM-183 Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW)

|

US Air Force

|

The USAF is pursuing hypersonic technology via its ARRW programme. Although the first test of the fully operational ARRW prototype in December 2022 was successful, ARRW’s flight testing records have been mixed since then. Despite expressing an interest in disbanding the programme in 2023, a recent test conducted by the USAF at Guam in March 2024 may lead to its resurgence.

|

|

Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile (HCAM)

|

US Air Force

|

The USAF also initiated the HCAM programme in 2022.

|

|

Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LHRW) or Dark Eagle

|

US Army

|

|

|

Tactical Boost Glide (TBG)

|

DARPA

|

|

|

Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC)

|

DARPA

|

|

China

|

Programme

|

Details

|

|

DF-17

|

China has conducted a number of successful tests of the DF-17, a medium-range ballistic missile specifically designed to launch HGVs, with a range of approximately 1,000 to 1,500 miles.

|

|

DF-41

|

The DF-41 ICBM has been tested and can be modified to carry a conventional or nuclear HGV.

|

|

DF-ZF

|

The DF-ZF HGV, with a range of about 1,200 miles, has been tested at least nine times since 2014 and was reportedly fielded in 2020.

|

|

Starry-Sky 2 (or Xing Kong-2)

|

According to US defence officials, China successfully tested Starry-Sky 2, a nuclear-capable hypersonic vehicle prototype, in August 2018. Unlike the DF-ZF, Starry Sky-2 is a “waverider” that uses powered flight after launch and derives lift from its own shockwaves. According to some reports, the Starry Sky-2 could be operational by 2025.

|

Russia

|

Programme

|

Details

|

|

Avangard

|

The Avangard is an HGV launched from an ICBM, giving it an “effectively unlimited range.” It is reportedly capable of carrying a nuclear warhead and according to Russian news sources, it entered combat duty in December 2019.

|

|

3M22 Tsirkon

|

Russia is also working on the 3M22 Tsirkon, which is a ship-launched hypersonic cruise missile, with a maximum range of about 625 miles. It was reportedly deployed on the Project 22350 Admiral of the Fleet of the Soviet Union Gorshkov in January 2023.

|

|

Kinzhal

|

Additionally, Russia has already fielded Kinzhal in Ukraine, a manoeuvring air-launched ballistic missile modified from the Iskander missile. Russian media claims Kinzhal possesses a top speed of Mach 10, with a range of up to 1,200 miles, along with the capability to carry a nuclear warhead.

|

India’s progress

BrahMos Aerospace is working on the BrahMos-II missile, which is fashioned after the Russian 3M22 Tsirkon. However, the project has encountered several delays, with the expected time of deployment now projected to be around 2028. Parallel to this, the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) has been working on the Hypersonic Technology Demonstrator Vehicle (HSTDV) since 2008, which uses scramjets to reach an altitude of up to 20 km, with speed reaching Mach 6. The HSTDV was first successfully tested in June 2019. This was followed by another successful demonstration in September 2020 up to an altitude of 30km at speeds up to Mach 6. The last test was carried out on 27 January 2023. India is the fourth nation after Russia, the US and China to demonstrate hypersonic capability.

Although there are reports that the Agni-5 may be an HGV, the DRDO has denied such capabilities. Additionally, while the “Shaurya” and “Sagarika” missiles can reach hypersonic speeds, their overarching characteristics are more like ballistic missiles, and they do not fall in the category of hypersonic weapons.

The last test was carried out on 27 January 2023. India is the fourth nation after Russia, the US and China to demonstrate hypersonic capability.

In February 2024, IIT Kanpur inaugurated India’s first hypersonic test facility which possesses a testing platform for cruise missiles with speeds up to 10 km/s. It was funded by the Department of Science and Technology and Aeronautical Research and Development Board under the DRDO and will enable simulations of hypersonic conditions for upcoming space and defence projects, such as the BrahMos-II programme.

The necessity for hypersonic deterrence

As previously discussed, the fact that hypersonic weapons are extremely difficult to track and intercept by existing defence systems is what makes them a particularly dangerous novel form of weaponry. The US has developed Aegis ships equipped with the sea-based terminal (SBT) capability, which can engage some hypersonic threats in the latter part of the missile’s flight path, what is known as the terminal phase. Aegis SBT is the only active defence for countering hypersonic missile threats at the moment.

The US Space Development Agency (SDA) is working on a Tracking Layer constellation which is envisioned as a global network of sensors meant to act as a defence shield against ballistic and hypersonic missiles. The Missile Defense Agency’s (MDA) national security mission, designated USSF-124, includes six satellites designed to track hypersonic missiles. Four of these are for the SDA’s Tracking Layer while two more are for the MDA’s own Hypersonic and Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor (HBTSS) programme, which has recently been launched. The HBTSS sensors are designed to maintain high-fidelity tracks of the threats and provide the data to interceptor missiles that would attempt to shoot them down. Both the Tracking Layer and HBTSS are pieces of a planned multi-layered missile-defense architecture. The fire control technology that HBTSS is seeking to demonstrate is required for intercepting hypersonic weapons.

The HBTSS sensors are designed to maintain high-fidelity tracks of the threats and provide the data to interceptor missiles that would attempt to shoot them down.

When it comes to India, while undertaking the BrahMos-II and HSTDV projects are certainly welcome steps in the development of its hypersonic capabilities, no such urgency has been shown in the domain of hypersonic defence. The DRDO has completed phase-1 of its land-based Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) programme and is currently working on phase-2. In April 2023, the DRDO and the Indian Navy also successfully conducted the trial of a sea-based interceptor missile.

Hypersonic weapons are poised to play a dominant role in future warfare thanks to their speed and manoeuvrability, which makes them particularly hard to detect, not to mention their ability to carry nuclear warheads. Given the constant threat posed by China and its growing prowess in hypersonic weapons development, India needs to accelerate its efforts not only in hypersonic weapons, but deterrence as well. It would be prudent for the DRDO to incorporate hypersonic defence into its BMD programme. The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) can also serve as a viable candidate for developing space-based sensors, which could potentially be developed along the lines of the US SDA’s ongoing project in the field.

Prateek Tripathi is a Research Assistant with the Centre For Security Strategy and Technology at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV