The world faces a complex nexus of interconnected issues, ranging from climate change and resource depletion to economic disparities and geopolitical tensions. These challenges pose formidable obstacles to ensuring access to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food for all. About 924 million individuals (11.7 percent of the world's population) face acute food insecurity—a rise of 207 million since the pandemic. Despite decades of progress, the world is still grappling with the triple challenge of undernourishment, overweight/obesity, and nutritional deficiencies related to diet and micronutrients. The fight against hunger and food insecurity will require sustained and targeted efforts, particularly in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, where the world’s largest populations suffer from chronic hunger. Reducing undernutrition has far-reaching implications for health and poverty reduction.

The fight against hunger and food insecurity will require sustained and targeted efforts, particularly in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, where the world’s largest populations suffer from chronic hunger.

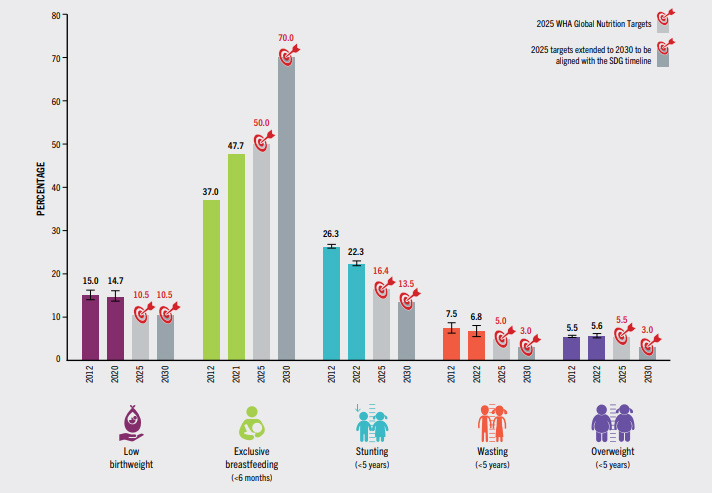

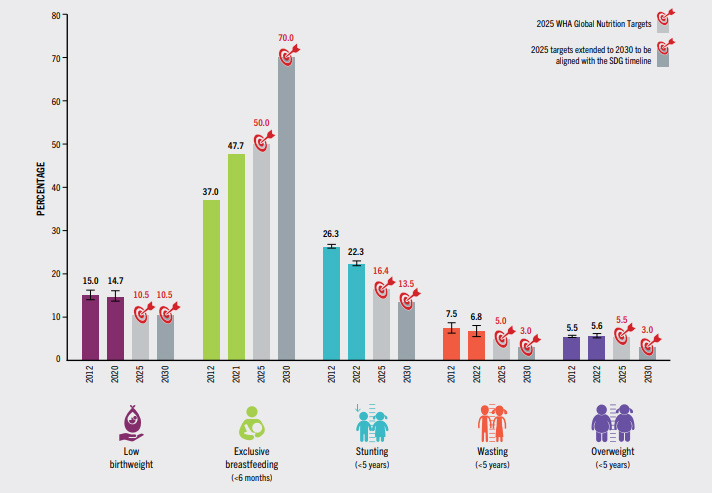

A set of six global nutrition targets were set with a focus on Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2.2: “End all forms of malnourishment”. The WHA targets have been extended to 2030 to align with the SDG Agenda 2030. In light of the increasing prevalence of adult obesity and NCDs (Non-Communicable Diseases), a WHA target was set to halt the increase of adult obesity and thus reduce the risk of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD) by 25 percent by 2025.

Around 735 million people or 9.2 percent of the global population are undernourished. Africa has the highest rate of hunger—almost 20 percent—compared to Asia (8.5 percent), Latin America and the Caribbean (6.5 percent), and Oceania (7.0 percent). Nearly 600 million people are expected to suffer from chronic undernourishment by 2030, underscoring the enormous difficulty in reaching the SDG aim of ending hunger. Around 23 million more have been affected due to the war in Ukraine. Similarly, nearly 119 million more were affected due to the epidemic and the conflicts. The prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity globally remained steady for the second year in a row after a substantial increase from 2019 to 2020, however, it was still much higher than the pre-pandemic level of 25.3 percent.

As per the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2023 hunger is at a moderate level worldwide. However, Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have serious levels of hunger at GHI 27.[1] Europe and Central Asia have the lowest 2023 GHI score, at 6.1, which is regarded as low.

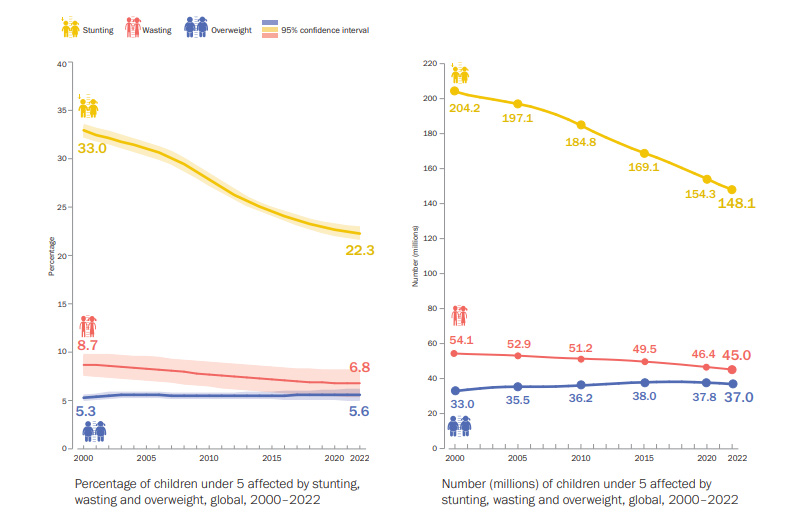

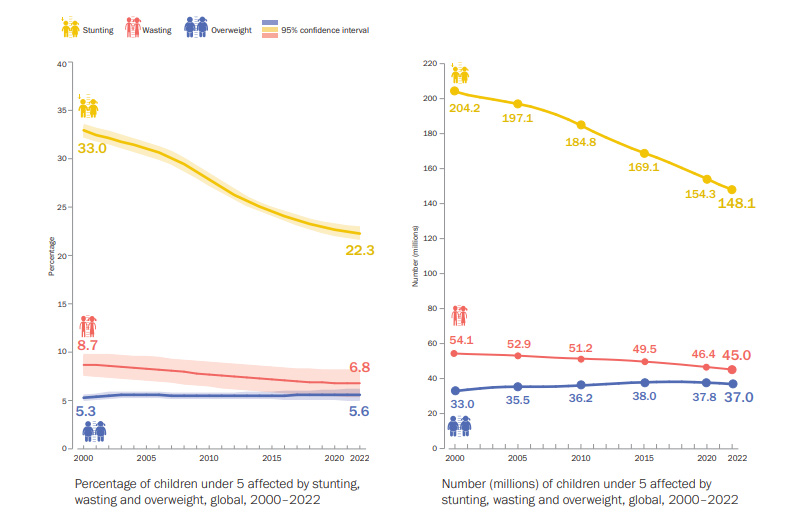

According to the Joint Malnutrition Estimate 2023, stunting has affected 148.1 million (22.3%) of all children under five years of age. Wasting continues to stagnate, with an estimated 45 million (6.8 percent) children in 2022. The incidence of overweight/obesity has slightly lowered since 2020, with 37 million (5.6 percent) children affected in 2022 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Prevalence and number of under-five children affected by Stunting, Wasting and Overweight

Source: UNICEF / WHO / World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates,2023

Stunting rates have, indeed, decreased throughout the last 20 years. However, in certain regions, stunting in under-five children is still high, with Asia (76.6 million) and Africa (63.1 million) having the highest rates. Sub-Saharan Africa's stunting rates have increased, for reasons of poverty and inequality, lack of access to healthcare, and rising food insecurity. The worst-affected region is Southern Asia, at 30.7 percent prevalence way higher than global prevalence at 22 percent, where three out of 10 children are stunted. The average prevalence of overweight is the lowest in Asia's subregions, at 2.5. The prevalence of wasting in the Southern Asia subregion is 14.1 percent, greater than the 6.7 percent global average. Overall, diet diversity, maternal education, and the level of family poverty are the main factors that explain variation in child stunting rates in South Asia. Furthermore, in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, stunting is a result of inadequate young child and maternal nutrition and poor sanitation.

The worst-affected region is Southern Asia, at 30.7 percent prevalence way higher than global prevalence at 22 percent, where three out of 10 children are stunted.

Worldwide, 45 million (6.8 percent) children under five are wasted, far higher than the SDG goal and Global Nutrition targets of 3 percent and 5 percent, respectively. Southern Asia accounts for 56 percent (25.1 million) of under-five wasting and about 27 percent live in Africa. Of the 31.6 million children affected by wasting in Asia, almost 80 percent live in Southern Asia. Evidence from South Asia shows factors such as low maternal body mass index, short maternal height, a large proportion of households in the lowest quintile of wealth, and a lack of maternal education are linked to wasting in children under five. The Lancet had estimated an increase in child wasting by 14.3 percent (6.7 million), with around 58 percent of children in South Asia and roughly 22 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa as an impact of COVID-19.

Obesity in both children under five and adults is on the rise. The burden of being overweight in both under-fives and adults has been on the rise. Globally, about 37 million (5.6 percent) of children under five are overweight. Almost half of the total live in Asia (17.7 million); the other big proportion is in Africa (10.2 million). Trends indicate a significant increase in overweight children in Oceania and Australia and New Zealand in the decade between 2012 and 2022. The number increased from 9.3 million to 13.9 million in Oceania, and from 12.4 million to 19.3 million children in Australia and New Zealand in the last decade. The majority of regions are off-track to achieve the targets set for reducing obesity in children.

Evidence from South Asia shows factors such as low maternal body mass index, short maternal height, a large proportion of households in the lowest quintile of wealth, and a lack of maternal education are linked to wasting in children under five.

Among the Global Nutrition targets, only exclusive breastfeeding appears to be on track to achieve at least the 50-percent rate by 2025 (Figure 2). In 2021, 47.7 percent of children were exclusively breastfed worldwide, with South Asia, East Africa, and Southeast Asia above the global average at 60.2, 59.1, and 48.3 percent respectively. Northern America, Oceania, and western Asia regions are off-track with no progress or worsening trends for low birth weight and exclusive breastfeeding. Some parts of Asia, Latin America, and Oceania show worsening trends in childhood obesity.

Figure 2: Progress on Global Nutrition Targets

Source: FAO 2023

Almost 15 percent of children born worldwide have a low birth weight (less than 2,500 g). Progress in reducing low birth weight has stalled in recent decades. South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America are the three main regions with low birth weight, with 24.4, 13.9, and 9.6 percent respectively. Reducing low birth weight by 30 percent by 2030 has made slow progress. Multiple pregnancies, infections, and non-infectious diseases can lead to low birth weight and negative outcomes such as neonatal mortality, poor cognitive development, and future. cardiovascular disease risk. Interventions that improve early and sustained access to quality prenatal care and prenatal services, nutritional counseling, and early primary newborn care are critical to preventing and treating low birth weight.

Adult obesity continues to increase in all regions, tripling over the last four decades. More than a billion people in the world are obese—650 million adults, 340 million teenagers, and 39 million children. This number continues to grow. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that by 2025, around 167 million people—adults and children—will be overweight or obese. Among the world's major causes of mortality, obesity, and overweight rank fifth. It also increases risk factors for noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers.

As a result of the supply chain disruption, there was food waste as there was less demand, and farmers who lacked proper storage were left with unsold produce.

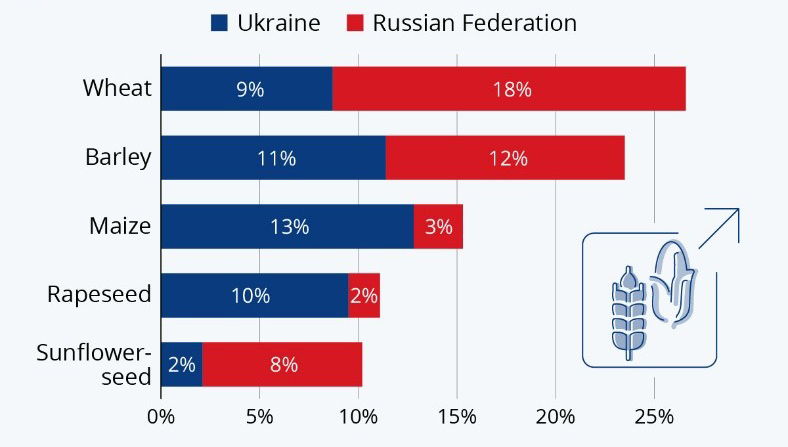

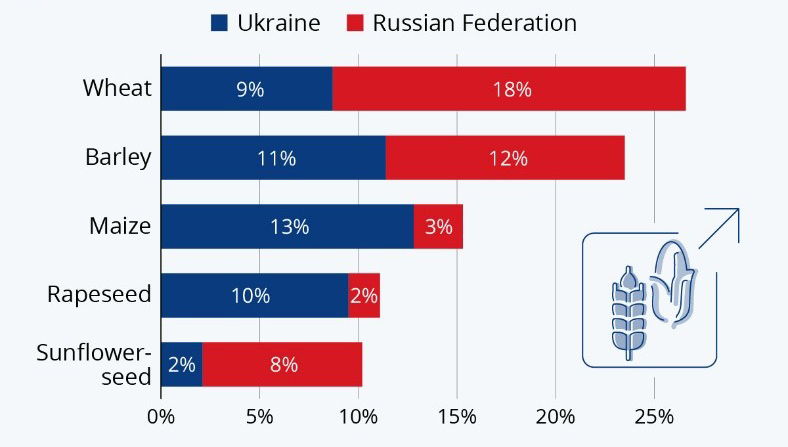

The COVID-19 epidemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict, have combined to cause the worst food catastrophe since World War II, with up to 1.7 billion people living in poverty and hunger, a number that has reached a record high right now. As a result of the supply chain disruption, there was food waste as there was less demand, and farmers who lacked proper storage were left with unsold produce. Those nations where food insecurity is more common were severely impacted by supply chain disruptions. Travel restrictions and the closure of labour facilities to manage the epidemic had an impact on food production cycles that relied on migrant workers. The war has disrupted agricultural production in the region, leading to decreased yields and displacement of rural communities. The geopolitical implications have reverberated across global markets, impacting the availability and affordability of key food commodities.

Figure 3 indicates Russia and Ukraine are significant producers of maize, wheat, and barley, making up, on average, 27, 23, and 15 percent of worldwide exports between 2016 and 2020. Even the World Food Programme, which sources 50 percent of its grain supply from the Ukraine-Russia region, is currently dealing with sharp cost hikes as a result of its ongoing efforts to address global food crises. The downturn in the economy has exacerbated pre-existing disparities and affected the availability of food.

Figure 3: Ukraine and Russia’s Global Export Share, 2016-2020

Source: Statista

To end the intergenerational cycle of poverty and eradicate all types of malnutrition, policymakers must intensify their efforts. Raising the implementation of high-impact, nutrition-specific treatments across all low- and middle-income nations is predicted to reduce stunting by 40 percent and yield economic benefits of around US$417 billion. An economic of US$11 will result from every US$1 invested in stunting reduction. Beyond the fields of agriculture and health, more players and sectors must be involved. To combat malnutrition, a “food systems” approach calls for comprehensive policies that take into account both supply and demand. To create a resilient food system, it is imperative to strengthen strategic action to meet people's needs both now and when the crisis passes.

Shoba Suri is a Senior Fellow with the Observer Research Foundation

[1] GHI scores the share of people who are undernourished, child wasting rate, child stunting rate, and child mortality rate.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV