-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The impact of high economic growth on health and nutrition outcomes in Gujarat has been mixed.

Gujarat is one of the major industrialised states of India with consistently high rates of economic growth and high urbanisation. The latest data (2015-16) show that Gujarat, after Jammu and Kashmir, is the fastest growing among the bigger Indian States. Agriculture in Gujarat was once considered to be a major bottleneck. It contributed only around 15% of the incomes, demonstrated negative growth in the nineties, and still employed more than 50% of the workers. However, in a major turnaround, Gujarat’s agricultural GDP grew at an unprecedented 8 per cent per annum during 2002-03 to 2013-14, more than double the all-India figure of 3.3 per cent, and even better than that of Punjab during the Green Revolution.

Among the largest state economies, per capita income is the highest in Gujarat. Gujarat is the Indian State with the lowest levels of unemployment in the country — with only 9 per thousand unemployed, compared to a national average of 50 per thousand. Poverty incidence in Gujarat is lower than that of India for both rural and urban areas as well. This stellar performance on the economic front consolidated the power of the then Chief Minister Narendra Modi, and in a way, launched his career in the national politics.

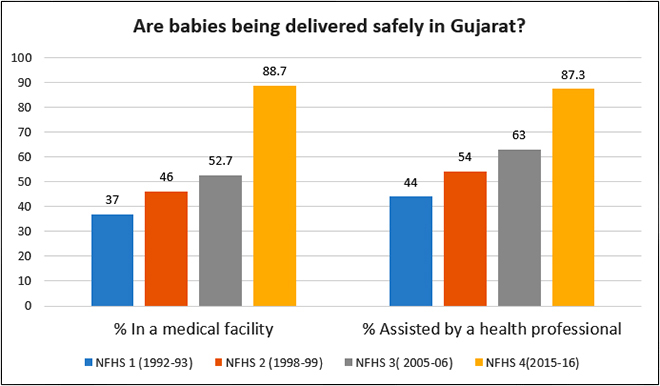

The impact of high economic growth on health and nutrition outcomes in the state has, however, been mixed. One area where Guajarat has performed well on the average is the improvement in the proportion of safe deliveries as the following graph shows . The jump in institutional/safe deliveries in the state is often attributed to the Chiranjeevi Yojana, which was launched in 2005 with the aim of stabilising population growth by reducing the fertility rate, lowering infant mortality rate and maternal mortality ratio. However, some more recent studies have rejected the claim and noted that the earlier studies may not have addressed self-selection of women into institutional delivery, reporting inaccuracies by hospitals, or any increases in institutional deliveries over a period marked by high economic growth.

Source: NFHS (Various years)

Source: NFHS (Various years)

One area where Guajarat has performed well on the average is the improvement in the proportion of safe deliveries.

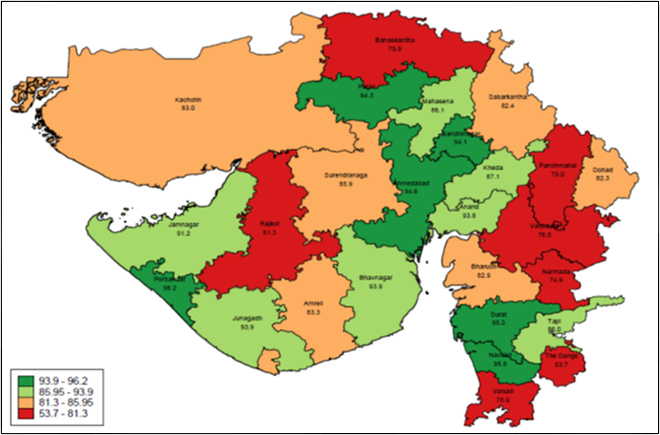

While the proportion of deliveries assisted by a trained health professional — both at hospitals and at home — have improved substantially on the average, inter-district inequities remain a major issue yet to be addressed. As the following map demonstrates, there are huge variations — from the Dangs where the proportion of safe deliveries are just 53.7%, to districts like Surat, Navsari and Porbandar reporting more than 95%.

Total births assisted by a doctor/nurse/LHV/ANM/other health personnel (%) in Gujarat

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

Over the last decade, Gujarat has been able to bring down the percentage of women aged 20-24 years who were married before the legal age of marriage from 39% to 25%. The period also saw a substantial reduction in the proportion of women aged 15-19 years who were already mothers or pregnant, from 12.7% in 2005-06 to 6.5% in 2015-16. Both infant mortality rate and under-five mortality rates have declined over the last decade — IMR declined from 50 to 34, while U5MR declined from 61 to 43.

Despite a high dependency to the private sector for both outpatient (84.9% cases) and for inpatient (73.8% cases), Gujarat has relatively lower proportion of out of pocket spending on health care at 63.7%. On the average, India depends lesser on the private sector — 74.5% for outpatient and 56.6% for outpatient cases — but has a higher proportion of out of pocket spending on health care at 74.4%. States like Kerala, West Bengal, Odisha and Uttar Pradesh have more than 80% of out of pocket spending on health care, as analysis by Brookings India has shown. The percentage of households reporting catastrophic expenditure (health expenditure exceeding 25% of usual consumption expenditure) are just 6.8% in Gujarat, while the all India percentage is almost double.

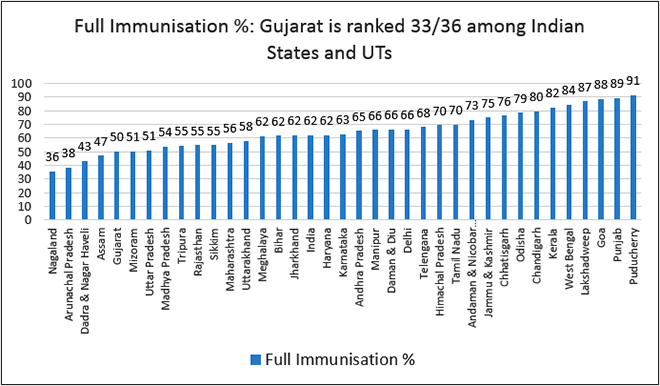

However, latest data suggest that some coverage indicators like immunisation — a concern for a long time for Gujarat — have shown an extremely worrying worsening trend in Gujarat. According to government sources, Gujarat was one of the few states in India where full vaccination coverage declined during the seven-year period since NFHS-2 (from 53% in NFHS-2 to 45% in NFHS-3). Further, despite some improvement, the present coverage level is even now close to what it was at the time of NFHS-1 in the nineties (50%).

Full immunisation coverage has improved to 50.4% in NFHS-4. However, Gujarat is still close to the bottom among Indian States. In 2005-06, among all the states, Gujarat had the 10th lowest level of full immunisation coverage for children age 12-23 months, but in 2015-16, among all the 36 states and Union Territories, it is the fifth lowest as the following graph shows. India’s overall performance was slightly worse than Gujarat a decade back, but now, Gujarat fares much lower than the India average.

Full immunisation coverage has improved to 50.4% in NFHS-4. However, Gujarat is still close to the bottom among Indian States.

Reportedly, Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh are the only two states where the incidence of TB has actually increased over the last decade, and similar reversals are possible for many diseases if immunisation levels remain low in Gujarat. Immediate action is needed to address the low immunisation uptake as high morbidity burdens can potentially wipe out the economic gains built over the years. According to the latest data released by ICMR on state-level disease burdens, tuberculosis is currently the third leading cause of death and disability in Gujarat, a situation worse than 1990.

Source: NFHS (Various years)

Source: NFHS (Various years)

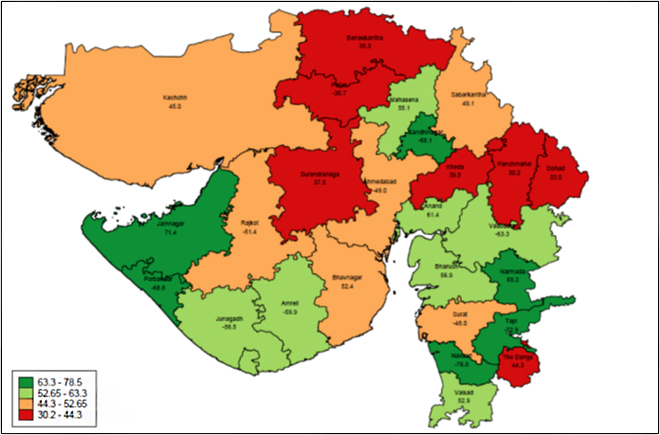

The inter-district variability of immunisation coverage points to the possibility of cross-learning between the relatively better off districts and the lagging districts. As the following map demonstrates, districts like Panchmahal, Patan, Dohad, Banaskantha, Surendranagar and Kheda with under 40% coverage of full immunisation can learn from districts like Jamnagar, Tapi and Navsari reporting more than 70% full immunisation. It goes without saying that even the relatively better performing districts will have to improve tremendously to achieve universal access.

Children aged 12-23 months fully immunised (BCG, measles, and 3 doses each of polio and DPT) (%) in Gujarat

Source: NFHS-4

Source: NFHS-4

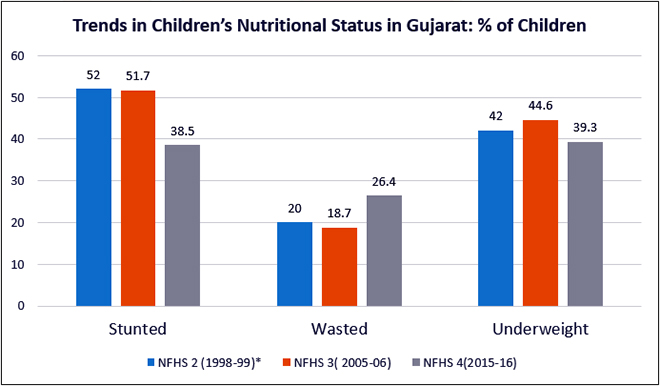

Nutrition has also been a similar concern for Gujarat for long. According to the ICMR data, malnutrition and dietary risks are the top two risk factors driving the most deaths and disability. While the last decade saw slow progress in the proportion of stunted and underweight children, the proportion of wasted children has gone up substantially.

Source: NFHS (various years)

Source: NFHS (various years)

* Note: NFHS-2 numbers are for under-3 children while the rest are for under-5 children

For an economic powerhouse, Gujarat’s rankings for standard nutrition outcome indicators remain extremely poor. As the following set of graphs show, data from 2015-16 demonstrate that among all States and Union Territories, Gujarat ranks 29 in terms of childhood stunting, 34 in terms of childhood wasting and 32 in terms of childhood underweight. This requires immediate policy attention as undernutrition at this scale can adversely affect sustainability of economic development through various pathways.

Source: NFHS

Source: NFHS

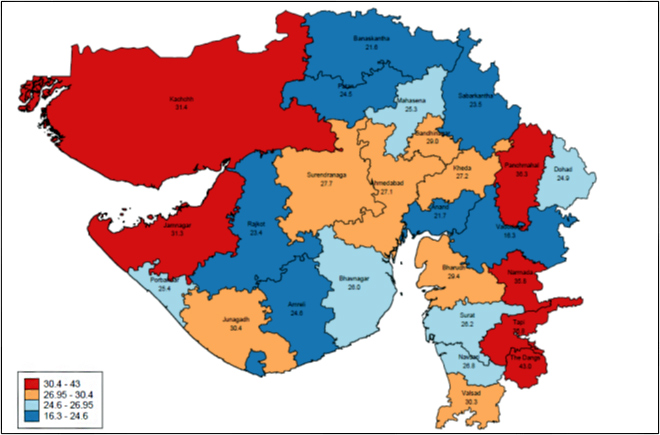

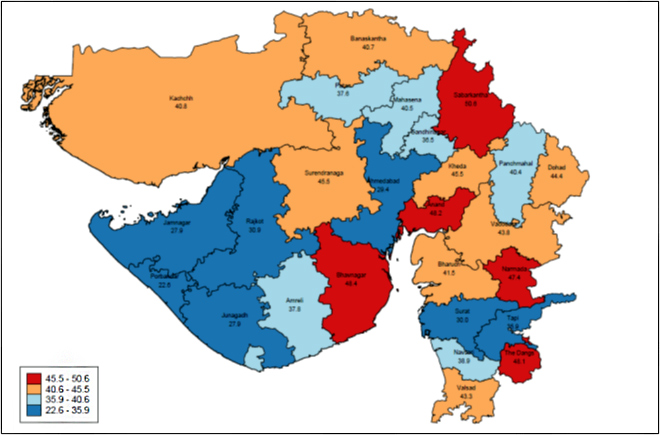

The proportion of children undernourished also shows a very high variability between districts within Gujarat. As the following sets of maps show, districts like Valsad, Junagadh, Jamnagar, Kachchh, Narmada, Tapi, Panchmahal and the Dangs are reporting very high (>30% ) proportions of childhood wasting. Similarly, Kheda, Surendranagar, Narmada, the Dangs, Anand, Bhavnagar and Sabarkantha report very high (>45% ) proportions of childhood wasting. High-burden districts as well as worse performing talukas from the other districts will have to be identified immediately for corrective action.

Children under 5 years who are wasted (weight-for-height) in Gujarat (%): District-wise

Source: NFHS-4

Source: NFHS-4

Children under 5 years who are stunted (height-for-age) (%) in Gujarat: District-wise

Source: NFHS-4

Source: NFHS-4

Gujarat is in the phase of a transition where the public policy challenges presented by over-nutrition are in addition to those posed by undernutrition, instead of replacing traditional challenges of under-nutrition. Obesity and overweight among Gujarati men and women have increased substantially over the last decade.

Part of the explanation for Gujarat’s less-than-satisfactory performance in health and nutrition lies in the inequalities that make the state “look more and more like islands of California in a sea of sub-Saharan Africa,” whereby, on the average, the state is “climbing up the ladder of per capita income while slipping down the slope of social indicators,” as Dreze and Sen commented about India’s social sector performance elsewhere.

The Assembly elections give the political leadership and the citizens an opportunity to rethink and streamline the strategies as well as pathways to improve the health and nutrition status of Gujarat, a top priority to sustain the economic performance of the state.

Maps created by Rakesh Kumar Sinha (ORF Data Labs) and district level data compilation by Divya Vishwanathan.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Oommen C. Kurian is Senior Fellow and Head of Health Initiative at ORF. He studies Indias health sector reforms within the broad context of the ...

Read More +