-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The barriers erected by the Global North are intended to facilitate domestic investment in green energy industries but they will curtail the production and export of green goods and services in the Global South.

Entrenched subsidies for fossil fuels and coal-fired grid-based electricity, cost of capital, weak electricity grids, regulatory barriers, and constraints on the availability of minerals and land are often identified as barriers to scaling the adoption of renewable energy (RE) in the Global South. But tariff barriers (TB) and non-tariff barriers (NTB) that curtail the import of RE and other green goods currently being instituted in the Global North are significant barriers to scaling RE in the Global South.

In the past countries in the Global South imposed TBs and NTBs to protect and nurture their nascent industries. Countries in the Global North countered by pushing a neo-liberal agenda often through the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank (WB) and the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The IMF and the WB attached conditions to their loans that forced recipient countries to adopt neo-liberal policies. The WTO contributed by making trading rules that favoured free trade in areas where the Global North is strong but not where they are weak such as in agriculture and textiles.

Today, the positions are reversed. TBs and NTBs imposed by the Global North to protect green industries far exceed those imposed by poor countries. The barriers erected by the Global North are intended to facilitate domestic investment in green energy industries but they will curtail the production and export of green goods and services in the Global South. This in turn will slow down global decarbonisation.

Provisions to protect free trade are ambiguous in climate frameworks. According to Article 3.5 of the UNFCCC and Article 2.3 of the Kyoto Protocol, measures taken to combat climate change should not constitute a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade and should be implemented to minimise adverse effects, including on international trade, and social, environmental and economic impacts on other Parties. In the context of climate and environment, the WTO contradicts its mandate to promote free trade stating that members can adopt trade-related measures aimed to protect the environment and to ensure sustainable development. The ambiguity embedded in these provisions allows the Global North to protect and subsidise the domestic production of RE and other low-carbon goods supposedly in the interest of climate action.

The first and most important protectionist measure of the Global North came from the USA when it passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), pledging to provide over US$360 billion in tax credits, grants, subsidies and loans to boost US clean-tech manufacturing. The IRA is effectively an implicit subsidy to incentivise domestic production equivalent to an NTB. The IRA was intended as part of the US strategy to weaken China’s dominance in the green economy. Only firms that source parts and materials from the US or its trade partners can benefit from the IRA, excluding the EU (European Union) and Japan, which do not have a free trade agreement with the US.

Earlier US interventions that are barriers to free trade include the Chips and Science Act of August 2022 which aims to strengthen American manufacturing, supply chains, and national security, and invest in research and development, science and technology, and the workforce of the future to keep the US as the leader in the industries of tomorrow, including nanotechnology, clean energy, quantum computing, and artificial intelligence. In 2022, the US also authorised the use of the Defence Production Act (DPA) to accelerate domestic production of clean energy technologies. Five key energy technologies that are covered under the act are (1) solar (2) transformers and electric grid components (3) heat pumps (4) insulation and (5) electrolysers, fuel cells, and platinum group metals. These interventions are effectively NTBs for the import of green goods.

The EU’s Green Deal Industrial Plan which is among the responses to IRA is destined to enhance the competitiveness of Europe's net-zero industry and support the fast transition to climate neutrality. It proposed the Net-Zero Industry Act, to provide a regulatory framework suited for the quick deployment of a net-zero industrial capacity, ensuring simplified and fast-track permitting, promoting European strategic projects, and developing standards to support the scale-up of technologies across the single market. It also announced the Critical Raw Materials Act and a reform of the electricity market design.

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), applies a levy on imported goods equal to the internal EU ETS-related carbon price so that both EU-produced goods and those imported into the EU face similar carbon cost pressures. However, sectors must use the CBAM phase-in period to decarbonise. The CBAM erects a high NTB to the import of energy technology and industrial products from the global south.

Green sectors in the USA and the EU will unsurprisingly, benefit from IRA, CBAM and other protective measures. But producers in other countries lose out so much that they could slow the green transition at the global level. 80-90 percent of trade on low-carbon such as the IRA and CBAM. Ironically, TBs and NTBs are low for carbon-intensive goods and high for low-carbon goods and TBs on low-carbon goods are higher than fossil fuel consumption subsidies. NTBs such as those put in place by the Global North have twice the impact of TBs in reducing trade and increasing emissions. Studies on TBs and NTBs on solar PV (photovoltaic) illustrate their negative impact on decarbonisation.

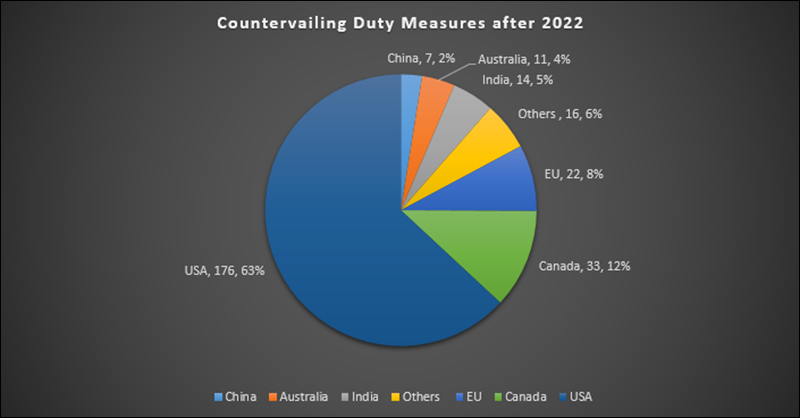

Half the solar PV manufactured in 2021 were traded which is more than 4 times since 2010. Since 2011, the number of antidumping, countervailing and import duties on solar PV increased from just 1 import tax to 16 in 2021 and many more TBs and NTBs are under consideration. In 2021, global solar PV-related trade increased by 70 percent from the 2020 value of over US$40 billion. Roughly 0.13 GtCO2e (giga tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent) is embodied in solar PV. Traded solar cells and modules result in 30-year lifetime net emissions reductions of up to 1.6 GtCO2e. An increase in solar power generation is expected to result in a reduction of emissions in a range of 50–180 GtCO2e between 2017 and 2060 in “business-as-usual” scenarios. Removal of half of status quo trade barriers will increase PV applications by over 7 percent and improve cumulative net carbon emissions reduction potential by 4–12 GTCO2e. Additional trade barrier impositions will result in global PV applications decreasing by 1.6 percent to 3.5 percent and cumulative net carbon emissions mitigation potential decreasing by up to 3–4 GtCO2e by 2060.

The protective measures implemented by the Global North in the context of solar PV and other green technologies could trigger a global subsidies race to attract investments in clean technology and production. This course is problematic in a world in which governments in the Global South have only a fraction of the access to public resources needed to finance national decarbonisation efforts compared to countries in the Global North. Economies characterised by public resource scarcity in the Global South will be hit hard by a subsidised race in clean-technology innovation and industrial decarbonisation. Trade and investment could be negatively impacted by CBAM and other border measures that restrict imports based on origin and the carbon intensity of traded goods, resulting in further market segmentation. The protective measures of the Global North which is responsible for over 90 percent of carbon emissions since 1850, is signalling the message that wealthy nations prefer building as much domestic industry as possible over decarbonising as quickly as possible. TBs and NTBs of the Global North that prioritise buying local rather than buying green (from the Global South) will slow down decarbonisation in the Global South. This means a slowdown of global decarbonisation because the Global South accounts for over 60 percent of emissions today.

The protective measures implemented by the Global North in the context of solar PV and other green technologies could trigger a global subsidies race to attract investments in clean technology and production.

Source: Brugal

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ms Powell has been with the ORF Centre for Resources Management for over eight years working on policy issues in Energy and Climate Change. Her ...

Read More +

Akhilesh Sati is a Programme Manager working under ORFs Energy Initiative for more than fifteen years. With Statistics as academic background his core area of ...

Read More +

Vinod Kumar, Assistant Manager, Energy and Climate Change Content Development of the Energy News Monitor Energy and Climate Change. Member of the Energy News Monitor production ...

Read More +