-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Delhi’s EV policy leads India’s green mobility shift — but the road ahead needs stronger data, financing, and urban planning alignment

Image Source: Pexels

In August 2020, Delhi quietly took a bold step toward reshaping its transport future. The Delhi Electric Vehicle (EV) Policy was launched as a measure to introduce cleaner and quieter vehicles on the roads, and also as a broader intervention, one that sought to tackle air pollution, generate new forms of employment, and provide more accessible, comfortable mobility for its citizens. The scale of the challenge and the opportunity is indeed significant. With a population of over 20 million, Delhi is more populous than many countries and ranks among India’s most economically advanced states. Its per capita GDP stood at around US$ 5,056 in 2020, driven by a mature, service-led economy that contributes over 70 percent to state GDP. Its fiscal indicators are equally strong, with a consistent revenue surplus since 2015 and a fiscal deficit below 3 percent.

With a population of over 20 million, Delhi is more populous than many countries and ranks among India’s most economically advanced states.

Yet, despite these advantages, Delhi faces a mobility crisis. In 2021, the city had over 12 million private vehicles. Public transport options like the Delhi Metro and bus services account for a considerable share of daily ridership—estimated between 37 and 50 percent—but lack coordination and comprehensive coverage. Meanwhile, air pollution remains one of Delhi’s most visible and damaging public health challenges. Transport emissions contribute approximately 20–23 percent of fine particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5) in the city’s air.

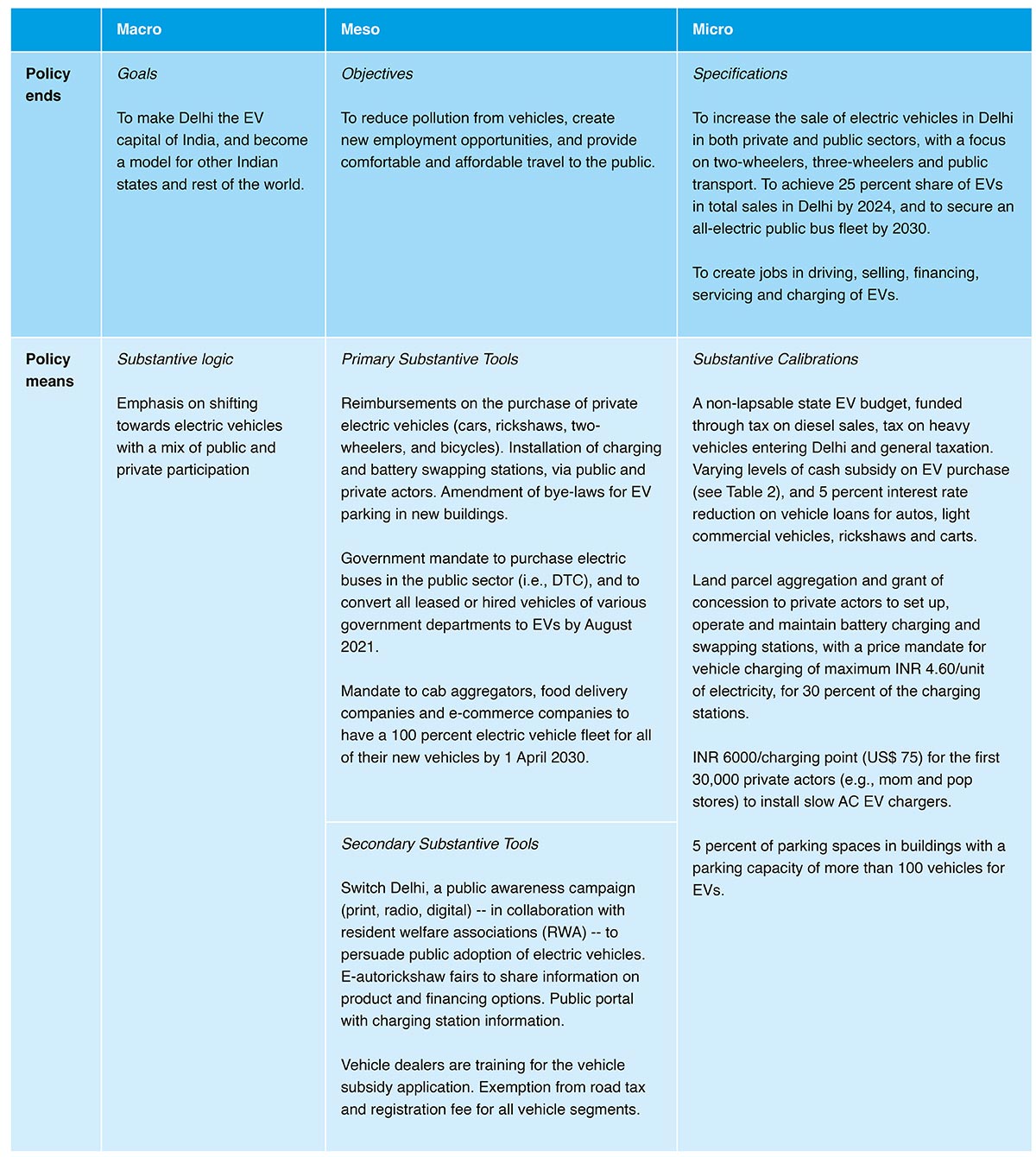

The EV policy was crafted as a response to this multidimensional challenge. It set ambitious, time-bound targets: to ensure that 25 percent of new vehicle registrations are electric by 2024, that 70 percent of the public bus fleet is electric by 2025, and that the entire public bus fleet transitions to electric by 2030. Importantly, the policy also sought to catalyse systemic change—not just by incentivising EV purchases, but by reshaping the surrounding infrastructure and market ecosystem. Table 1 below shows the policy mix of Delhi’s EV policy.

The first row shows the goals, objectives and specifications that the policy aims to achieve. The second row indicates the tools and calibrations used to pursue the goals, objectives and specifications. The policy targets three main vehicle categories. First, the public bus fleet, with a mandate to the Delhi Transport Corporation (DTC). Second, commercial vehicles—especially those used for delivery and ride-hailing services—which were initially supported through subsidies and later nudged through phased mandates. Third, private passenger vehicles, where uptake is encouraged through financial incentives and public information campaigns. These campaigns have targeted housing societies, malls, and workplaces to build broader social legitimacy for EV adoption.

Table 1 Policy Mix of Delhi’s EV Policy 1.0

Source: Based on DDC et al (2022). Table adopted from Cashore and Howlett (2007). All US$ figures in 2022 US$; 1 US$~INR 77.

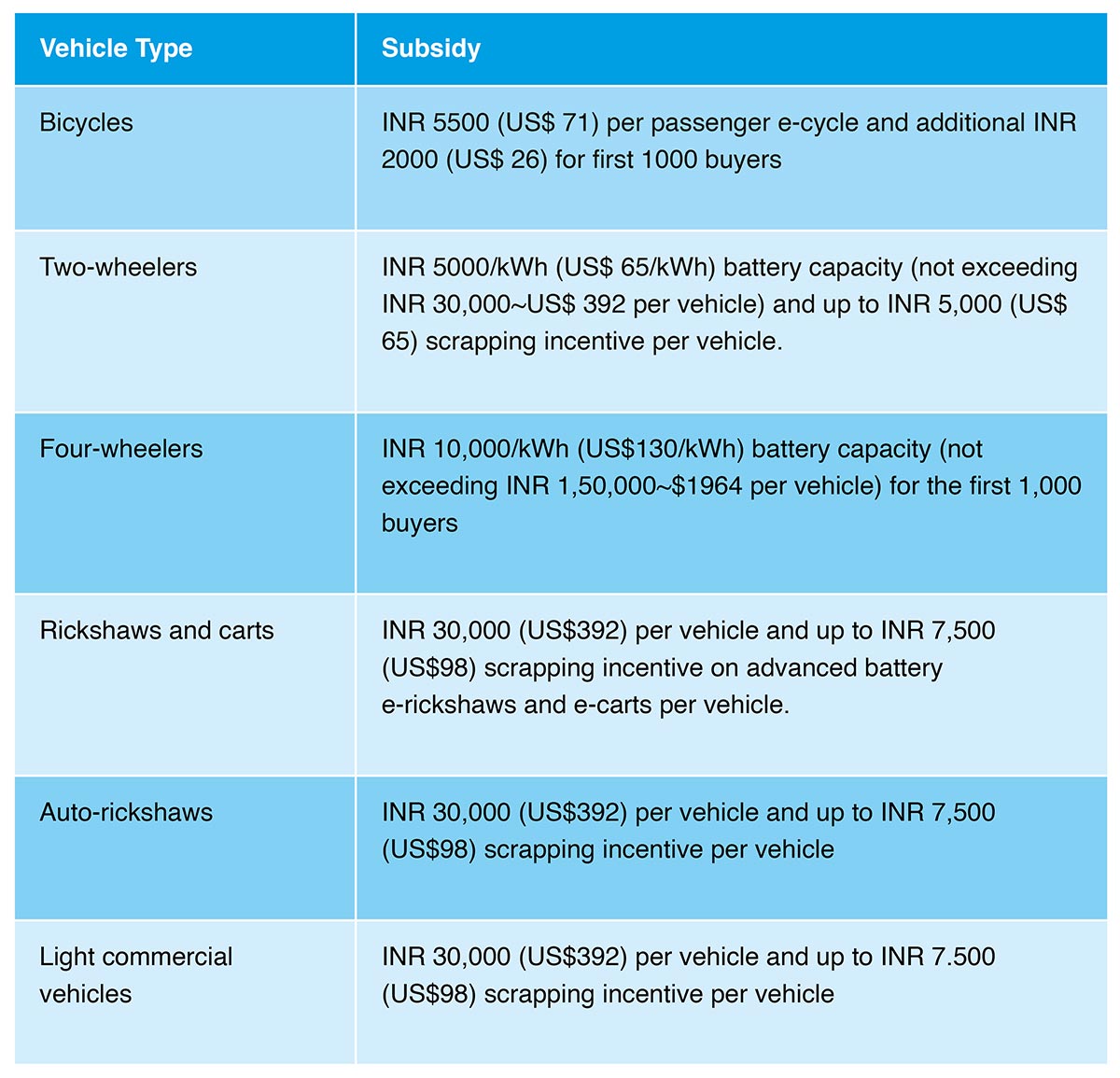

On the infrastructure front, the policy recognises that uptake will depend as much on convenience as on cost. Delhi is committed to a dense charging network, to place one public charging point every three kilometres. This has involved regulatory changes to building codes, public-private partnerships for land use, and direct subsidies for setting up charging points.

Table 2: Subsidy by Vehicle Category in Delhi EV Policy 1.0

Source: DDC et al 2022. All US$ figures in 2022 US$; 1 US$~INR 77.

The Delhi EV Policy 1.0 has three areas for improvement. First, based on the Avoid–Shift–Improve (ASI) framework, the policy primarily emphasises the ‘Shift’ component—encouraging a transition to low-carbon modes of transport (i.e., EVs). It places relatively little emphasis on the ‘Avoid’ aspect (such as reducing the need for travel through better land-use planning) or on ‘Improve’ strategies (such as raising fuel efficiency standards of conventional vehicles), largely due to jurisdictional limits. Delhi’s government does not control vehicle emissions norms or urban land use policy, both of which remain under the purview of the Union government. However, going forward, exercising these tools together might bring greater benefits.

Second, despite the promise of a non-lapsable EV budget and the 5 percent interest subvention for commercial vehicle loans, these policy calibrations never materialised. Although reasons are not known for the first, the second calibration might not have materialised because the agency in charge of it–the Delhi Financial Corporation (DFC)– lacked the capacity to roll it out. A development finance agency in a highly urbanised region, the DFC has been largely dormant, and alternative ways of making this financing possible are needed, including from general taxation or banks. Similarly, long-term viability and maintenance of electric public buses will require getting the DTC’s house in order, a high-loss-making agency of the government.

A development finance agency in a highly urbanised region, the DFC has been largely dormant, and alternative ways of making this financing possible are needed, including from general taxation or banks.

Finally, Delhi needs a mobility survey–just like much of India. Vehicle registrations are a good starting point, but they need to be matched with household characteristics like income, housing type, commuting patterns and vehicle use behaviours, to craft a sounder policy for transition to EVs. For instance, housing types of current and potential EV users are important to identify parking spaces and charging needs across a variety of dwellings, ranging from electric rickshaw users in unorganised colonies to luxury EV users in standalone villas. Business associations can play an important role in actualising such surveys.

Overall, Delhi is well-positioned to continue on its journey towards mobility transition, learning from its past successes (highest per capita EV registrations in 2023 across Indian states) and identifying areas for improvement.[1] However, that will require better data on mobility patterns, adequate policy capacity with its agencies to support the different tools in the complex mix, and a policy which also considers reducing the citizens’ need for travel. Imagining the EV transition as one of the components of the larger goal of urban sustainable development can aid in designing such policies, which bring success for businesses, the public and governments.

Mohnish Kedia is a PhD Candidate at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP), National University of Singapore.

[1] State-wise EV sales data obtained from Lok Sabha Unstarred Question Number 3482, Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, 10 August 2023.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Mohnish is pursuing his PhD at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP), National University of Singapore. He is theoretically interested in policy ...

Read More +