-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Korean leaders’ meet and welcome thaw in Sino-Indo relationship can positively impact global strategies in the 21st century.

Two events that unfolded rather unexpectedly on Friday, 28 April 2018, could spell a significant turnaround in a world besotted with myriad geopolitical complexities, especially in the Indo-Pacific — the hotbed of conflicting interests and actions in the 21st century. These two events could potentially also have a calming effect on a world fraught with concerns over growing signs of recession of the liberal world order and rise of protectionism, which are threatening to reverse the gains of globalisation.

Friday’s meeting between the Korean leaders in the border village of Panmunjeom on 27 April is expected to trigger a transformation of the strategic course of the world order in the decades to come. Probably the most significant diplomatic rendezvous since the Reykjavik Summit between US President Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev that sealed the fate of the Cold War and started the laborious and, yet unfulfilled, journey towards comprehensive nuclear disarmament. The meeting between Kim Jong-un, the Supreme Leader of North Korea and Moon Jae-in, President of South Korea in the border village could also give a decisive push towards de-escalating the growing tensions in the region and pave way for an official end to the Korean War. A peace treaty, replacing the fragile armistice of 1953 between the US, North Korea and China, is expected to finally establish long-term peace and stability in over six decades.

Friday’s meeting between the Korean leaders in the border village of Panmunjeom on 27 April is expected to trigger a transformation of the strategic course of the world order in the decades to come.

The warmth with which the two met has shifted the fulcrum of the diplomatic discourse to Seoul — away from Washington’s recent caustic rhetoric of labelling Kim as a “madman with nuclear weapons” and berating the North Korean leader as “this crazy fat kid.”

The effects of this shift, which is feared to undermine Washington’s stewardship, is reflected in the Western media’s take on the prospect of denuclearisation. A recent article in CNN by Jamie Matzl, Senior Fellow at Atlantic Council, deemed the proposed meeting between President Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un in May as a zero-sum game for the US. The article warned against the US prematurely legitimising what “Pyongyang has sought for decades” and that any Trump-Kim dialogue would lead to “a reduction in tensions and a nod toward ending the state of war on the Korean Peninsula — in exchange for very little.” The statement leaves not much to the imagination regarding the intention of the US in keeping the peninsula perennially on the boil for its own vested interests.

A peace treaty, replacing the fragile armistice of 1953 between the US, North Korea and China, is expected to finally establish long-term peace and stability in over six decades.

A peace treaty, replacing the fragile armistice of 1953 between the US, North Korea and China, is expected to finally establish long-term peace and stability in over six decades.

There couldn’t be a firmer negation of such pessimism than the text of the joint statement issued after the meeting in the ‘Peace House’. Both leaders declared that “there will be no more war on the Korean Peninsula” and that “a new era of peace has begun.” The declaration, before spelling out the roadmap towards the achievement of such a momentous future, highlighted the commitment of the leaders “to bring a swift end to the Cold War relic of longstanding division and confrontation.”

However, given the vested strategic interests of the US in the Korean Peninsula vis-à-vis China’s containment, it is unlikely for America — which has blamed China (and Russia) of “undermining the international order” and hence, being the biggest threat to the world — to read the writing on the wall.

Given the vested strategic interests of the US in the Korean Peninsula vis-à-vis China’s containment, it is unlikely for America to read the writing on the wall.

A brief evaluation of the recent turn of events, and some crystal ball gazing, is, therefore, in order:

In March, when Kim boarded the train from Pyongyang to Beijing, the journey was claimed as an attempt to gain solidarity from President Xi Jinping, his key ally, as a direct consequence of the looming armed confrontation with the US. The announcement made earlier of a meeting between President Trump and Kim would have certainly played a catalytic role in prompting this hastily scheduled trip. While the Kim-Xi meeting itself was kept shrouded in mystery, with most media reports merely speculating on what was discussed, it is, however, worth noting that the announcement of the meeting at Panmunjeom came just one day after the conclusion of Kim’s visit.

In all likelihood, the chain of events unfolding since seems to have emanated from the discussions that ensued between President Xi and his North Korean guest. And Xi’s ‘invisible hand’ in what unfolded is conspicuous. The result might prove to be a ‘win-win’ solution for all involved, if the tweet by President Trump following the Kim-Xi meeting is to go by: “For years and through many administrations, everyone said that peace and the denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula was not even a small possibility. Now there is a good chance that Kim Jong Un will do what is right for his people and for humanity. Look forward to our meeting!”

Taking the media speculations on the Kim-Xi meeting forward, one could safely assume that a couple of possibilities could have triggered the successive events. One may argue that Xi could well have given two distinct options to Kim to gain strategic advantage over the US:

Taking the media speculations on the Kim-Xi meeting forward, one could safely assume that a couple of possibilities could have triggered the successive events.

China, by helping North Korea to dismantle its nuclear programme, can assume a moral high ground to stand by its ally in demanding withdrawal of the US forces from South Korea. South Korea would feel confident to secure peace with its estranged half, and work towards unification, as envisioned in the joint statement. The US (and Japan) will only be too happy with a denuclearised Korean Peninsula. Kim, as a precondition, is quoted to have said that North Korea would agree to dismantle its clandestine nuclear programme only if the US promises “not to invade his country.” The question here is whether the US will concede and withdraw from South Korea.

What trajectory the China-North Korea-US relationship takes in the days to come and whether such concessions are enough for Kim to accept total disarmament are likely to ascertain the veracity of this premise. Hopefully, such a scenario will facilitate prudent US-China engagement.

Irrespective of what it all adds up to, one thing is certain. Friday’s event marks a remarkable chapter that will change the course of global discourse, if not changing the course itself, of the world order and help in establishing global peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific.

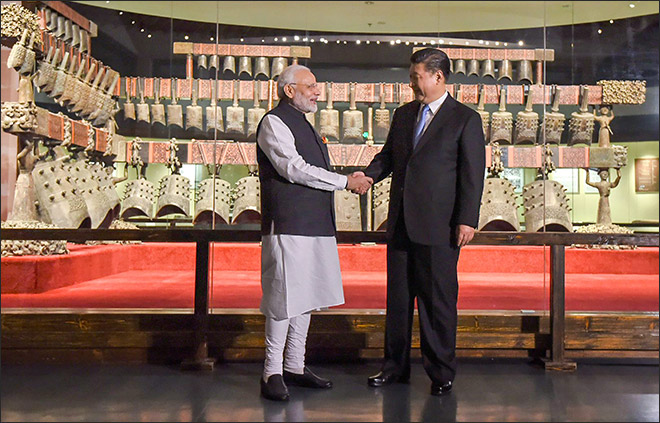

Coinciding almost to the hour with the meeting between Kim and Moon, Wuhan in China’s Hubei Province, about 2,000 kilometres across the Yellow Sea from Panmunjeom village, witnessed another significant development unfold. The ‘informal’ meeting between India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the China’s President Xi Jinping renewed hopes of ‘normalisation’ of relations once again between the two Asian giants. Considering that India and China together are home to nearly 40 percent of the global population, normal neighbourly relations between them is a precondition for global peace and stability.

The meeting in Wuhan gains much significance, as just a few months ago, the bilateral relationship had reached its nadir over the prolonged military standoff between the Indian and Chinese troops at the India-Bhutan-China tri-junction at Doklam. The standoff, which lasted for over two months in 2017, was perhaps the closest to a full-blown armed confrontation between the Indian and the Red armies since the 1962 war.

The meeting in Wuhan gains much significance, as just a few months ago, the bilateral relationship had reached its nadir over the prolonged military standoff between the Indian and Chinese troops at the India-Bhutan-China tri-junction at Doklam.

The meeting in Wuhan also assumes significance for other reasons. Coming close on the heels of Xi being anointed the Supreme Leader of the Communist Party of China (CPC) virtually for life, his determined push to his pet Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) — to which India is tangentially opposed primarily because of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), growing protectionism in the US owing to Trump’s ‘America First’ policy and the emerging preeminence of the Indo-Pacific on the global strategic chessboard, easy relations between two of the world’s fastest growing economies will act as a confidence building measure for the global community. Strong trade and economic engagement between India and China with assured peace on the border will lend a stabilising factor in the increasingly competitive global order. Globalisation, which, ironically is being dealt the biggest blow in the two western geographies — the US and Europe — that were instrumental for its creation, can flourish in this ‘Asian century’ if India and China, riding on their internal strengths, take the lead.

Strong trade and economic engagement between India and China with assured peace on the border will lend a stabilising factor in the increasingly competitive global order.

Strong trade and economic engagement between India and China with assured peace on the border will lend a stabilising factor in the increasingly competitive global order.

India-China relations are critical, especially now, as the US-China engagement is set to increase over the developments in the Korean Peninsula.

Despite the trade deficit, economic interdependence between the two Asian giants is the only assured link that is likely to keep both positively engaged with each other for mutual economic benefits. A case in point is the bilateral trade volume, which reached a record $84.44 billion in 2017, when sabre-rattling by their respective militaries also reached a crescendo during the Doklam standoff.

India-China relations are critical, especially now, as the US-China engagement is set to increase over the developments in the Korean Peninsula.

Interestingly, the BRI, which has been China’s single-minded obsession ever since it was announced by Xi Jinping in 2013, can actually provide numerous opportunities to foster mutually rewarding partnerships between the two, despite the former’s persistent rejection of China’s overall plan.

After all, the BRI is a combination of several of China’s old projects along with new mega connectivity and infrastructure plans covering half the globe. There are several similarities – almost duplications – when one considers several regional connectivity projects under the BRI and what is being pursued by India in parallel. For example, is there nothing in common between the BBIN and the BCIM? How different is the India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway than what the BRI wants to achieve in the same geography?

The ambitious multilateral connectivity maze that the BRI seeks to create is besotted by several strategic and economic coalitions — big and small — emerging in the Indo-Pacific. These coalitions can at once seem threatening if looked at from the point of view of geopolitical power games, but also at once seem pragmatic if viewed from the perspective of serving the common needs of all involved. India’s ‘Act East’ policy is bound to benefit from China’s infrastructure impetus. There would be huge benefits for India in terms of its connectivity with Central Asia and beyond if the BCIM, which seeks to connect Kunming with Kolkata, is extended to merge with CPEC.

At present, this may seem as unlikely as the miraculous turnaround in the relations between the two Koreas. But India and China must realise that both, though having conflicting strategic objectives, are using the same tools to achieve them. That BIMSTEC and RCEP, instead of providing strategic means for containment and counter-containment, can work together as parts of a larger whole, complementing each other than working at cross purposes.

Unless India and China, despite their mutual problems, don’t act with maturity, none of their pet connectivity projects will either connect or empower. It would be a golden opportunity lost if the conducive atmosphere created by Xi and Modi in Wuhan is not built upon with sagacity and a sense of purpose by both nations.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dhaval is Senior Fellow and Vice President at Observer Research Foundation, Mumbai. His spectrum of work covers diverse topics ranging from urban renewal to international ...

Read More +