-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

The real challenge is to translate the call for climate cooperation iterated at the G20 Summit in New Delhi into deeds given the divergent development status of the G20 countries

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

Energy and climate change are among the key themes addressed in the G20 New Delhi leaders’ declaration. There are no surprises in the declaration as most of the key points are reiterations of promises made earlier. Accelerating efforts to phasedown unabated coal-based power, creation of an international bio-fuel alliance, call for support for just energy transition, and the need for climate finance and technology transfer are among issues that are covered in the leaders’ declaration. The real challenge is in translating words into deeds given the divergent development status of the G20 countries.

Green House Gas (GHG) mitigation is a global public good and so each country has a built-in incentive to free-ride on the efforts of other countries. GHG mitigation is also nonrivalrous in the sense that one country’s mitigation action can benefit the whole world and no one country can be excluded from appropriating the benefits. Game theoretic models see climate negotiations as a ‘public-goods’ game in which incentives for cooperation are lower than that of other well-known games such as the Prisoners’ Dilemma. In a world with identical countries (say in terms of size and wealth), the climate framework mechanism provides little or no incentive for free-riding but problems arise when countries differ in wealth and size.

GHG mitigation is also nonrivalrous in the sense that one country’s mitigation action can benefit the whole world and no one country can be excluded from appropriating the benefits.

Polarisation between countries begins with differences such as size and wealth (geographic conditions, habits, resource endowments, governance structures etc. could be other differences not accounted for in game theoretical models). As per game theoretical models, if size is the only difference between countries, then large countries will place a higher value on mitigation while smaller countries will place a proportionally lower value. If wealth is a major difference, then poor countries will place a much lower value on mitigation compared to rich countries and will tend to free-ride. The current global climate negotiating framework assumes that all countries will assign the same value to mitigation efforts and that the differences between countries, if any, can be addressed through an appeal to scientific projections and moral sentiments. This has clearly not happened so far and it is unlikely that this will change anytime in the near future. Tomes of reports that project climate calamities for developing countries based on mathematical models and strong appeals to ‘save’ the planet from coal-burning power plants have not convinced coal dependent countries to significantly change their plans for power generation.

India which is a curious combination of large size (population numbers) and relative poverty (low per-person incomes) stands testimony to some of the predictions of game theoretical models. As a poor country India evidently has low incentives for mitigation action but as a large country it has relatively larger incentives for mitigation action (more victims of climate change and consequently more gain from mitigation action). However, the incentives to ‘free-ride’ as a poor country far outweigh the incentive to seek greater mitigation as a large country because its domestic logic is consistent with the former rather than the latter position. More immediate concerns such as poverty alleviation and consequently the need for economic growth are seen to be more important than the distant possibility of benefitting from climate mitigation action. India and other developing countries now carefully balance the need to portray themselves as climate apostles and climate victims in multilateral platforms such as the G20. For the first time in nearly two centuries, major ‘emerging powers’ such as India and China are not exactly rich. The ‘economic power’ of India and China is driven by quantitative factors (size measured in terms of population numbers) rather than qualitative factors such as economic efficiency and productivity. India’s per person gross domestic product (GDP) of US$ 2,388 (in current US dollars, 2022) is lower than that of Angola at US$ 2998.5. However, when India’s per person GDP is added over a population of over 1.4 billion grows into an aggregate GDP of over US$ 3.39 trillion (current US$) and puts India ahead of rich countries like Australia, Canada and France in terms of GDP. Even China’s per person GDP of US$12,720 is close to the world average GDP of US$ 12,647 and only a third of the OECD (Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development) GDP of US$43,260.

India and other developing countries now carefully balance the need to portray themselves as climate apostles and climate victims in multilateral platforms such as the G20.

The inconsistency between what may be called ‘quantitative’ attributes (reflected in national aggregate figures) of large economies like China and India and their ‘qualitative’ attributes (reflected in individual or per person figures) is key to understanding the large developing country dilemma in multilateral bargaining environments. Internal politics which is almost entirely focussed on qualitative attributes of the economy comes into conflict with their external statecraft which tends to project its quantitative attributes. Quantitative factors or the ‘size’ of a country defined by territorial borders is a critical parameter in the prevailing climate narrative. Global and national boundaries are used interchangeably to define and solve the climate problem. Borderlessness (globality) is invoked to frame the problem of climate change as one of global collective guilt while ‘borders’ are invoked to assign blame and responsibility. Borderlessness facilitates the democratisation of climate guilt as it spreads it around 7 billion people and reduces ‘per person’ guilt. On the other hand, ‘borders’ assist in the convenient allocation of the cost of combating climate change that favours smaller (in terms of population numbers) nations. Under this premise, if India or China break themselves into four or five economic regions with roughly 200 million people, they can no longer be labelled “large polluters” and hence will have little or no climate liability. This is an absurd outcome as all countries can break themselves up to avoid climate liability. However, the whole burden-sharing framing of what justice entails is structured in terms of the rights and responsibilities of ‘nations’ and so ‘nations’ rather than individuals who are seen to be endangered by climate change and affected by climate policy.

Borderlessness (globality) is invoked to frame the problem of climate change as one of global collective guilt while ‘borders’ are invoked to assign blame and responsibility.

As a nation, ‘not growing’ is not an option for developing countries because remaining ‘poor’ with millions of unmet aspirations is a greater threat to national and global security than climate change in the medium term. Take the case of India: since economic liberalisation in the 1990s, the quality of the Indian economy is seen as being directly dependent on double-digit economic growth rates. High economic growth rates are seen to be necessary to reduce levels of absolute poverty in India and provide clean and modern fuels to millions of households to raise their quality of life. Borrowing the words of Jennifer Beard, ‘development is the place that everyone is trying to get to, to complete themselves.’ While high economic growth rates need not necessarily translate into ‘development’ or ‘better quality of life’ for individuals at the bottom of the economic order, it is a ‘hope’ that holds people together. Calls for GHG mitigation action by rich countries without financial and technical assistance may preserve existing inequalities to trap millions in abject poverty. Ironically, the poor are already ‘green’ as they consume little or no fossil fuels directly or in the form of electricity. This is a status that they are neither aware of nor proud of and would only be too happy to get out of, if given a choice. There have been comments that developing countries’ ‘national interest’ concerns are a mere proxy for ‘elite interest’ and that the benefits of economic growth will be largely appropriated by the middle class and the elite. There may be some merit in this argument given the perverse inequalities that persist despite sustained economic growth, but as long as ‘nations’ remain the primary target for policy action, developing countries’ focus on ‘national interest’ cannot be contested. Climate change policy is fundamentally constructed through the twin lenses of national security and national economic strategy, the ‘nation’ is the master discourse which legitimises other discourses. In this light, the current climate change negotiating framework in platforms such as G20 that seek to facilitate the production of global public goods such as GHG mitigation without accommodating national interest is unlikely to result in cooperative outcomes.

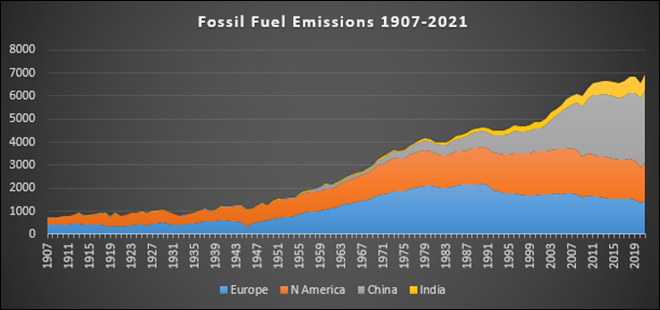

Source: Global Carbon Project

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ms Powell has been with the ORF Centre for Resources Management for over eight years working on policy issues in Energy and Climate Change. Her ...

Read More +

Akhilesh Sati is a Programme Manager working under ORFs Energy Initiative for more than fifteen years. With Statistics as academic background his core area of ...

Read More +

Vinod Kumar, Assistant Manager, Energy and Climate Change Content Development of the Energy News Monitor Energy and Climate Change. Member of the Energy News Monitor production ...

Read More +