India launched its ‘Smart City Mission’ to create 100 smart cities, capacitate urban local bodies, and allocated 480 billion INR in its 2015 Union Budget for this purpose. This led to an upsurge in Indian academia. The relevance, feasibility and sustainability of this laudable project was critically debated upon with a focus on the issue of ‘inclusion’. The issue of inclusion seemed significant keeping in mind the problem of inequity in well-serviced smart cities, that have a vast sea of poorly serviced slums and squatters. The structural inequities in Indian metropolitan cities has grossly manifested itself within the COVID-19 crisis by further exacerbating class-based hierarchies within citadels and ghettoes. While the painful exodus of millions of impoverished has unmasked systemic failures of the Indian statecraft, the unhygienic and insanitary conditions of shanties in metro cities - with minimal access to utilities and public health amenities - appear as ticking bombs for virus transmission.

The challenges of the pandemic on urban informal settlements drew significant international attention during March 2020, when contagions started surging in the global South. Researchers from the Institute of Development Studies, Sussex and the International Institute for Environment and Development could identify the manifold problems associated with urban informality to cope with the COVID crisis.

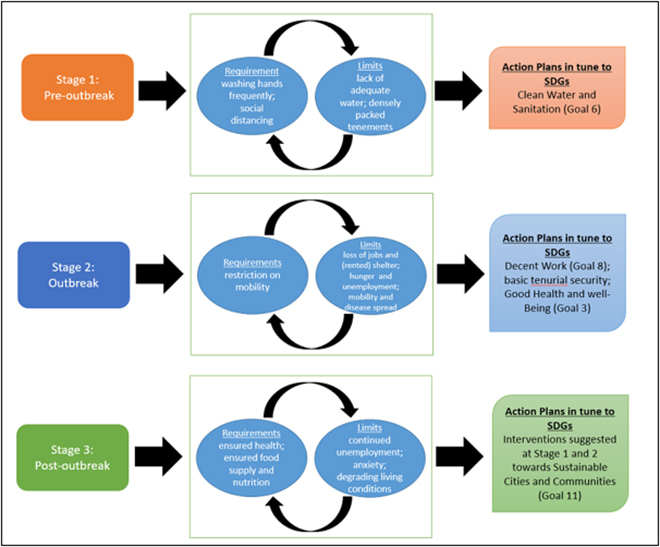

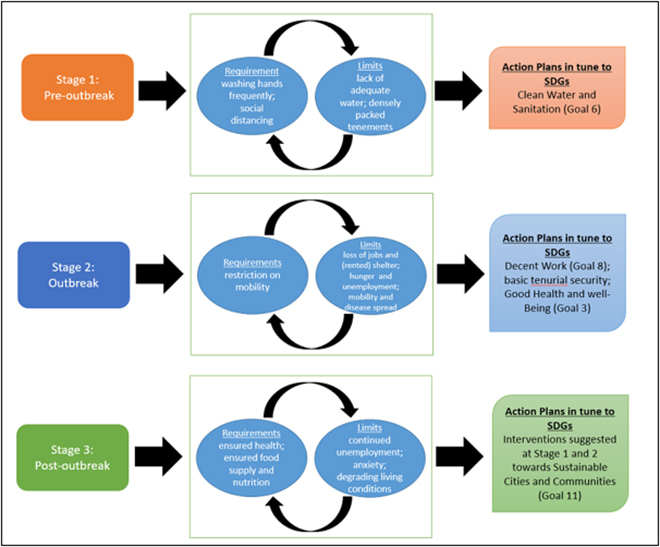

When perceived closely, COVID-19 in the slums and squatters of Indian metropolises like Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai, Kolkata, etc. presents a classic case of ‘wicked problems’ – a tangled mess of thread where it is difficult to know which to pull first. Densely packed urban environments with weak infrastructure and utilities can spread infections to multiple hosts. Unsafe water, inadequate sanitation, open drainage and refuse dumps are all factors attracting rodents and other parasites. These are prime reasons for the high prevalence of infectious diseases. Often labelled by city authorities as ‘informal’ or ‘illegal’, these settlements do not receive basic services such as piped water, sanitation or electricity. They are not served by primary healthcare facilities or regular solid waste collection, yet these settlements often house over half of a city’s population, being the only affordable option for many residents. Squatters can be the worst sufferers from the outbreak of coronavirus with continued and spiral effects during the pre-outbreak, outbreak and post-outbreak stages (illustration 1). Examples such as these demonstrate issues of social justice and inclusivity – thereby varying level of outcomes that projects like SMART CITY illustrate.

Illustration 1: COVID 19 challenges and suggested interventions in urban informal settlements of India

Source: Author (Mukherjee)

The countrywide lockdown has regulated the spread of infections to a certain extent. Observations from Dharavi illustrate quick actions implemented by the Bombay Municipal Corporation, such as, rapid testing, institutional quarantine and zonal segregations. With no massive outbreaks in other metropolitan shanties, this demonstrates sectoral scenarios of relief. All negative cases among the repatriates from different northern, western and central cities of India like Mumbai, Ahmedabad and Indore suggest that the risk of COVID-19 infection among migrants coming from cities to their villages is low or negligible. A study conducted by the Aajeevika Bureau on 1,129 migrants who returned to Rajasthan shows that none had coronavirus infection. The report attests that infection was introduced in the Indian cities by people who were infected overseas and returned to the cities over the last three months. It explains that working class people, labouring in construction sites and factories remain largely excluded with minimal interaction with other urban communities. The exclusion also sheds light on an ‘enforced social distancing’ as a part of everyday life for these workers. However, this data should not bring a sigh of relief to the administration. It should also not delay decisions about radical restructuring of Indian urban informality by implementing inclusive urban design plans and distributing social welfare measures.

COVID-19 has paralysed the Indian economy with shocking figures of GDP during the post COVID phase. Yet, this crisis can also be perceived as an opportunity to unfurl our collective imagination and efforts towards responding to the pandemic. It has mobilized awareness about the precariousness of urban squatters. There is a need to recognize bottom-up, need-driven initiatives with the potential to address local requirements.

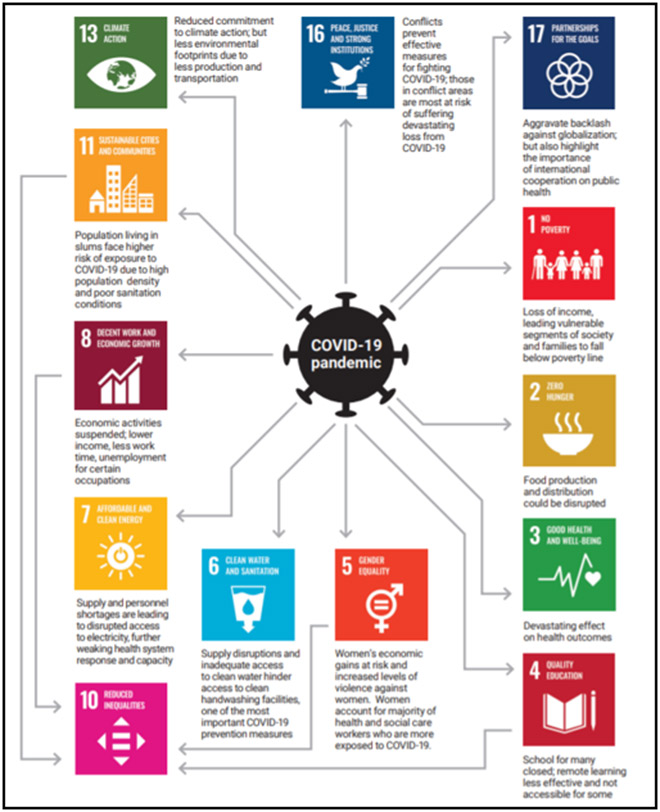

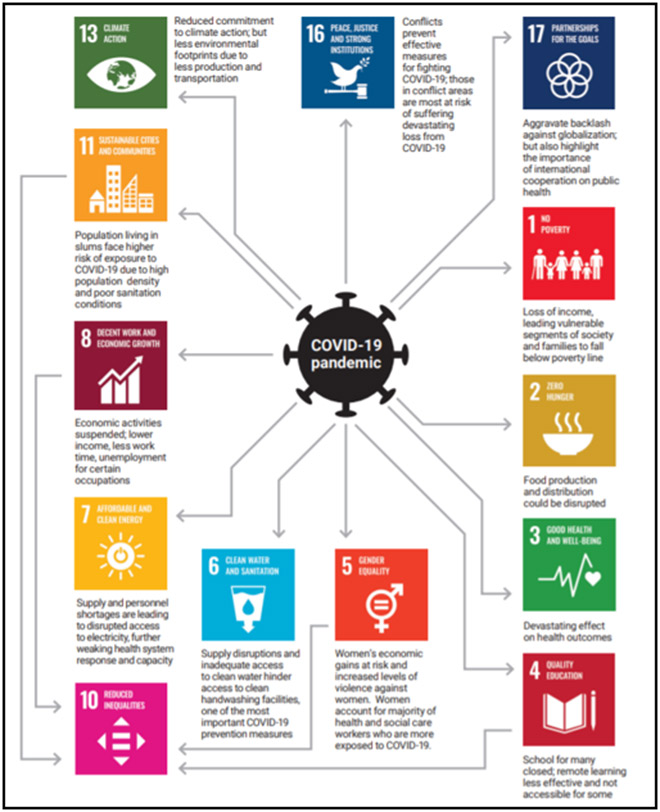

COVID-19 is the greatest opportunity to rethink and restructure urban informal settlements paying heed to the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and their overlapping intersections. For example, Goal 3: Good Health and Wellbeing, Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation and Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities, manifest converging socio-environmental agendas that need to be incorporated in urban (environmental) planning to design inclusive cities. This assumes greater significance within the urban informal context of developing countries, like India, where contemporary SMART city plans have neither been sensitive to the ‘informal’ poor nor the ecological commons, which acts as safety net for the former. COVID has undoubtedly infected the SDGs. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) has built scenarios to project the implications of the pandemic on each of the SDGs (illustration 2). But again, the situation has unravelled the pertinence of successful implementation of projects in tune with the SDGs.

Illustration 2: The implications of COVID-19 on implementation of SDGs

Source: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_report_socio-economic_impact_of_covid19.pdf. Accessed on May 7, 2020.

Source: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sg_report_socio-economic_impact_of_covid19.pdf. Accessed on May 7, 2020.

The Indian urban precinct cannot be an exception! The COVID crisis can be transformed into an opportunity by incorporating ‘sustainability’ in city planning through long-term and resilient measures that will mitigate risks from pandemics and enable cities to adapt to imminent crises, such as, climate shocks. A scoping exercise for Indian urban informal settlements through detailed identification of vulnerabilities and providing opportunities for involvement of grassroots organization and non-statist agencies is imperative. Effective approaches based upon existing programmes and networks, like Slum Development Initiative’s Indian Alliance transformed urban programming, National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF), Indian Waste Pickers’ Alliance, Right to Food campaign, etc. at different city scales must be capacitated towards this end. City specific action plans and their effective assessment through transparent municipal performance audits, based on quantitative and qualitative parameters can inform specific (and overlapping) SDGs, and make it more robust and inclusive by 2030 – the target year by which the goals are to be met.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Source:

Source:  PREV

PREV