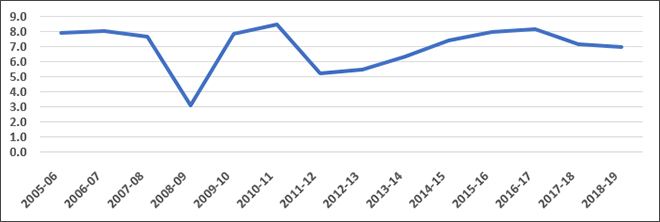

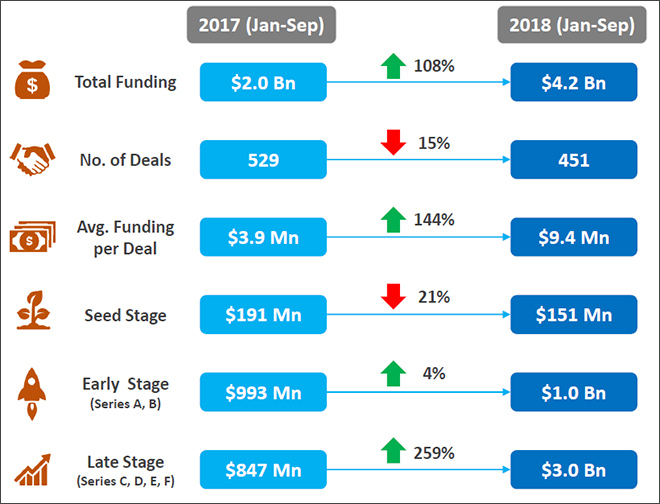

In 2014 election campaign, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) created an effective campaign on economic development, had succinctly expressed in its slogan “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas”. The background of that successful campaign can be contextualised by the dip in the GDP growth rates in 2013-14, as can be seen in Figure 1. The dip in the growth rates, starting from 2010-11, provided credence to the development pitch in that 2014 pre-election BJP campaign.

| FIGURE 1: Year-on-Year Percentage Growth Rates in GDP at Market Prices

(constant prices with base year 2011-12)

|

|

|

* 2014-15 = Third Revised Estimate, 2015-16 = Second Revised Estimate, 2016-17 = First Revised Estimate, 2017-18 = Second Advance Estimate

* Base year 2011-12 figures revised on account of new series of IIP and WPI

Data Source: dbie.rbi.org.in |

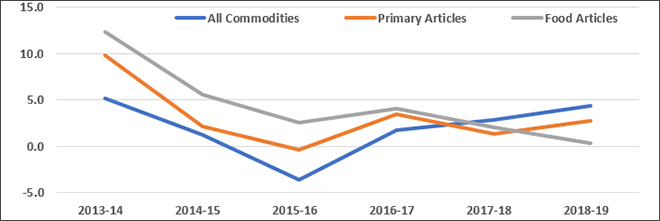

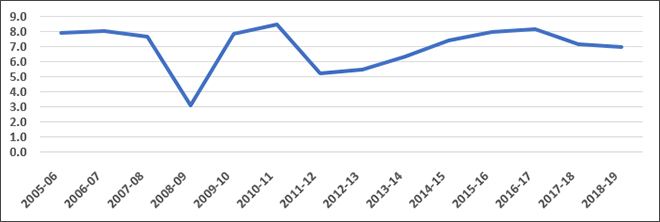

To compound the woe of then UPA-II government, the inflation was also in the upswing (Figure 2) – particularly severe in primary and food articles. Once the new NDA-II government took over, inflation eased up sufficiently – principally riding on decreasing food prices and falling international crude prices.

| FIGURE 2: Trends in WPI Inflation Rates (in percentage) |

|

|

* Base: 2011-12 = 100

Data Source: dbie.rbi.org.in |

The new NDA-II government had its economic priority cut out – in the revival of the macro economy. To do so, it kept on unveiling many schemes with opulent fanfare at frequent intervals, but out of those numerous lofty schemes four flagships were directly intended to kick-start the economy and generate employment and livelihood. And more surprisingly, none of these schemes is talked about in the current ongoing 2019 election campaign. The schemes were –

- Make in India, launched on 25 September 2014

(This was intended to make India an important investment destination and a global hub of manufacturing, design and innovation. Initially, the target was to increase the manufacturing share in GDP to 25 percent by 2022.)

- Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana, launched on 8 April 2015

(This was launched with the intention of “funding the unfunded” – by providing bank finance to that section of the population in the informal sector which is outside the reach of formal bank credit and therefore dependent on high-cost informal sources of loans. Original idea was to help very small businesses in generating a steady source of income.)

- Skill India, launched on 15 July 2015

(According to National Policy for Skill Development 2015, 104.62 million fresh job-seekers are estimated to enter the workforce, an additional 298.25 million existing farm and non-farm workers need to be skilled, re-skilled and up-skilled – putting the total skilling requirement at more than 402 million by 2022. This scheme was intended to fulfil that requirement.)

- Start-up India, launched on 16 January 2016

(This scheme was aimed at driving economic growth and generating large scale employment opportunities – by encouraging and nurturing innovation, and building a strong ecosystem for the start-ups in the country.)

Make in India

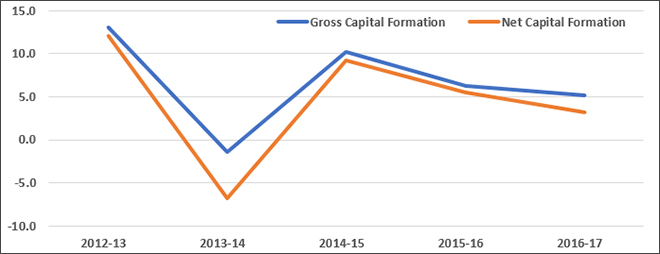

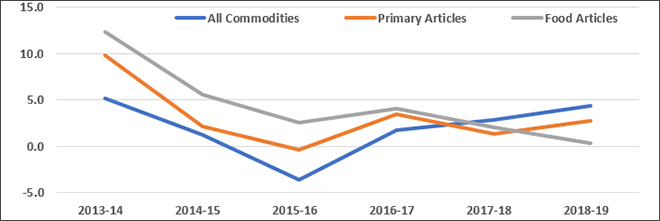

In 2014-15, growth rates of both gross and net capital formation increased but since then the rates are consistently on the decline. Capital formation is an indicator of investment in the real sectors of the economy, and therefore the desirable ambition of Make in India to have a booming manufacturing sector has visibly not taken off.

| FIGURE 3: Trends in Growth Rates of Gross and Net Capital Formation (in percentage) |

|

| Data Source: dbie.rbi.org.in |

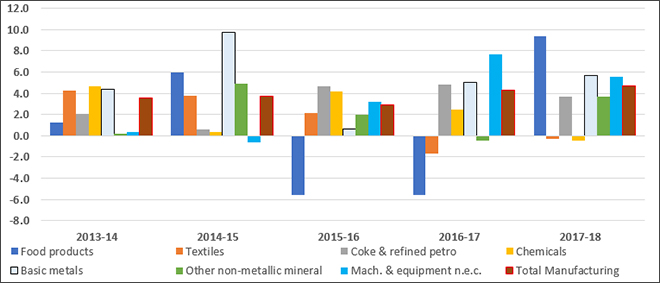

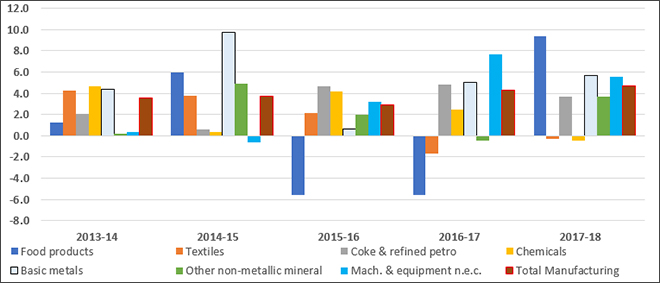

If one looks at growth rates of some of the important segments of manufacturing sector between the period 2013-14 and 2017-18 (Figure 4), then the stagnating situation becomes much clearer. During this period, segments like food products, textiles, non-metallic mineral, chemicals and machinery & equipment even experienced negative growth rates in production.

| FIGURE 4: Trends in Sectoral Growth Rates in Manufacturing (in percentage) |

|

|

* Growth rates are calculated using index numbers of different industry groups in manufacturing

Data Source: dbie.rbi.org.in |

With manufacturing share in GDP still languishing at 16.7 percent in 2017-18 (Provisional Estimate), Make in India – as a scheme – is an abject failure till now.

Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana

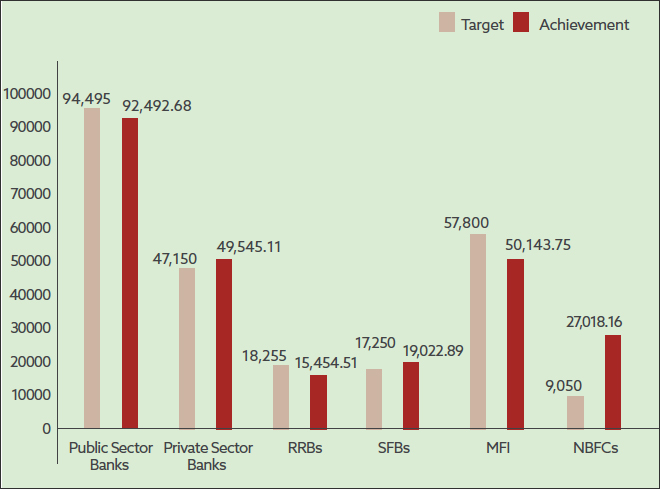

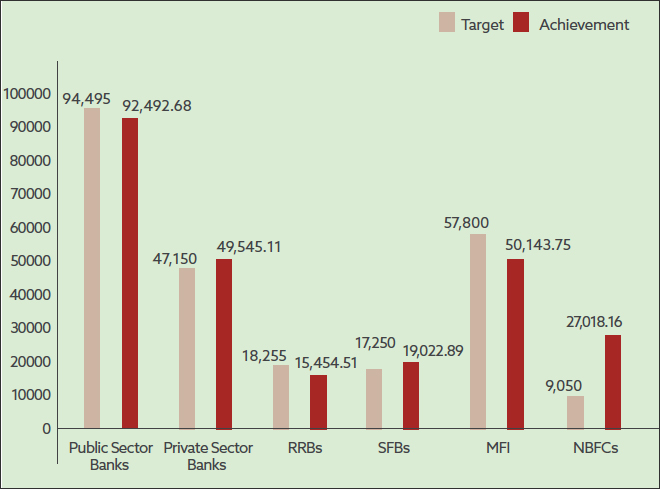

If one looks into total disbursements of credit under MUDRA, then it may seem that the scheme is a success. Different financial agencies, through which MUDRA loans are disbursed, performed well and total sanctioned amount exceeded INR 2.44 lakh crore target set for the year 2017-18.

| FIGURE 5: MUDRA: Target and Achievement in 2017-18 (in INR Crores) |

|

| Source: MUDRA: Annual Report, 2017-18 |

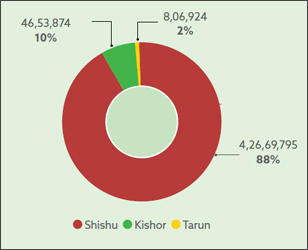

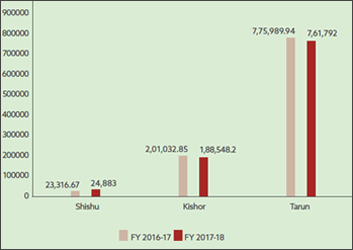

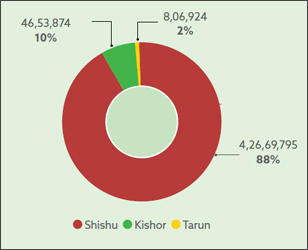

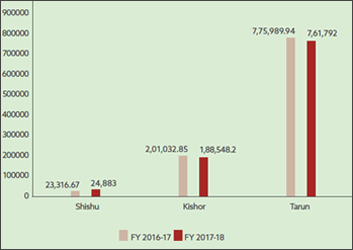

However, the devil here is in the details. MUDRA loans are disbursed in three categories – (a) Shishu (up to INR 50,000), (b) Kishore (above INR 50,000 & up to INR 5 lakh), and (c) Tarun (above INR 5 lakh & up to INR 10 lakh).

As can be seen from Figure 6, Shishu loans had the highest share of more than 88 percent in 2017-18, and the average loan size of Shishu loans was INR 24,883.

| FIGURE 6: Scheme-wise Details of MUDRA (in INR Crores and percentage) |

| Number of Accounts Scheme-wise Distribution |

Scheme-wise Average Loan Size |

|

|

| Source: MUDRA: Annual Report, 2017-18 |

The average size of INR 24,883 Shishu loans at best can be treated as one-time dole to most of the recipients. This paltry amount cannot generate a steady source of future income for them, and therefore the scheme falls short of achieving its primary macroeconomic objective to generate sufficient amount of employment and purchasing power in the economy.

Skill India

The idea behind Skill India was to create very short-term training modules to skill, re-skill and up-skill potential workers who will be needed once the macroeconomic boost through schemes like Make in India and Start-up India materialises. In the absence of such widespread macroeconomic boost, the scheme has been pushed into the background during recent times.

National Skill Development Policy 2009 during UPA-I set a target of skilling 500 million people by 2022. In the beginning of the year 2015, Union Minister of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship reiterated that target for Skill India. But, as mentioned earlier, during the actual launch in July 2015 the target was revised to 400 million by 2022.

Astonishingly by the middle of 2017, the government abandoned the goal of training 400 million (or, 500 million) people by 2022. Same Union Minister, who announced the target of 400 million by 2022, said – “We don’t want to chase any number. Whether it is 150 million by the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) and 350 million by ministries – we are delinking it, not attaching any number to it. It will be demand driven instead of supply driven”.

A quick check of Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY) website shows the current status as “approved for four years (2016-2020) to benefit 10 million youth with allocated budget of INR 12,000 crores”. Apart from quoting numbers of enrollment, ongoing training, assessed, passed, certified candidates the dashboard of PMKVY also mentions – “Due to financial year end activity target allocated for FY2017-18 is being recomputed. The target will be updated on the dashboard shortly”.

This sums up the story of Skill India in a nutshell. This was not unexpected either, as debates on unemployment figures raged in recent times. And, in the absence of any gainful employment, skilling remained an irrelevant policy making activity (in spite of the existing flurry of numbers on PMKVY dashboard). Unfortunately, the scheme with the most relevant macro enabler of growth (human capital) thus could not take off – in spite of cumulative effort of previous and current regimes.

Start-up India

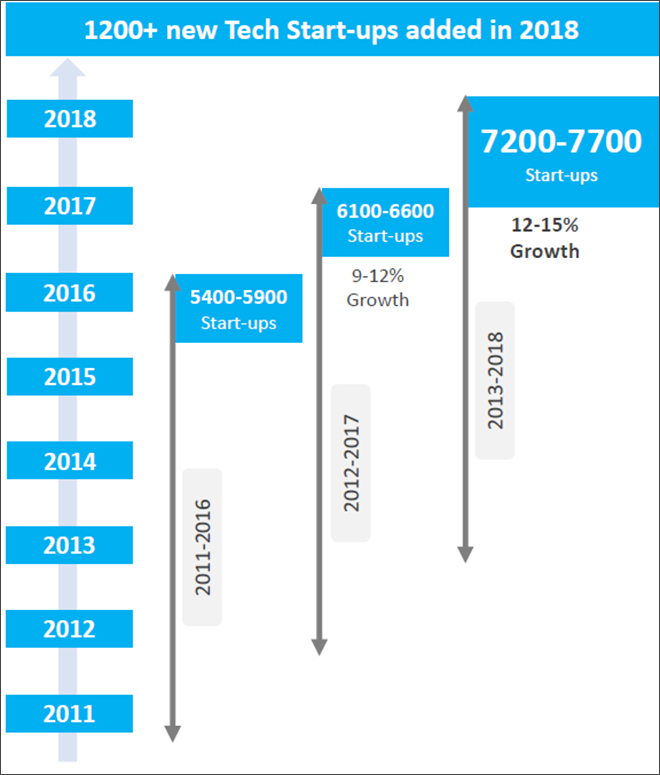

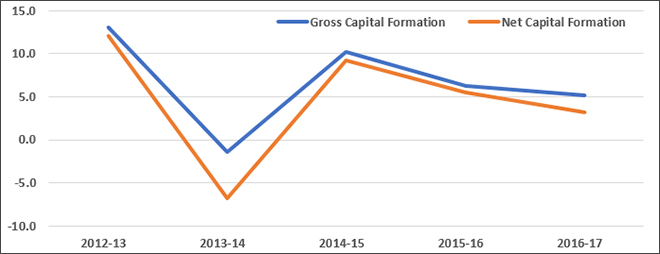

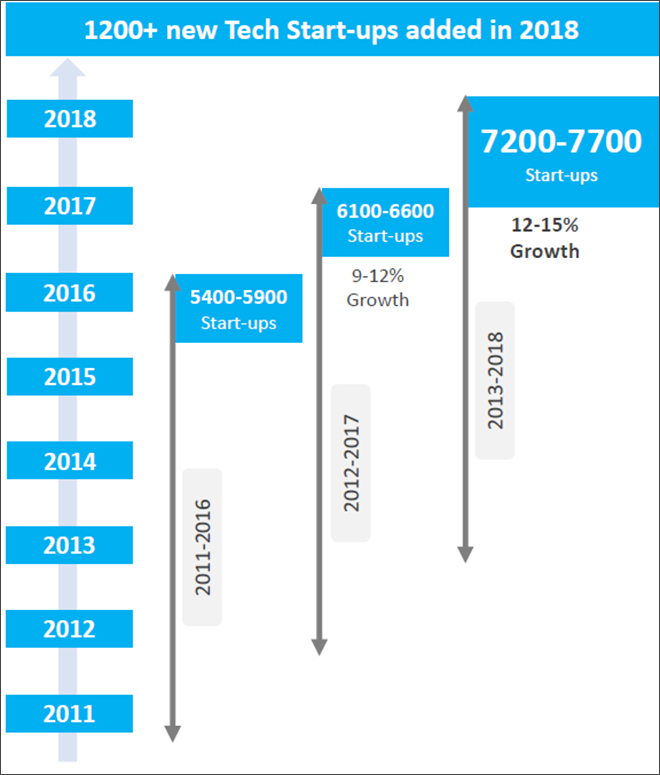

The most structured data on tech start-ups are available in the NASSCOM report, and that corroborates the fact that in spite of hiccups in-between Indian tech start-ups are growing in numbers and the rate of growth is healthy (Figure 7). If overall growth is considered, one can legitimately argue that Start-up India has made a positive contribution in Indian start-up ecosystem in recent years.

| FIGURE 7: Growth in Tech Startups |

|

| Source: NASSCOM-Zinnov Tech Startup Report, 2018 |

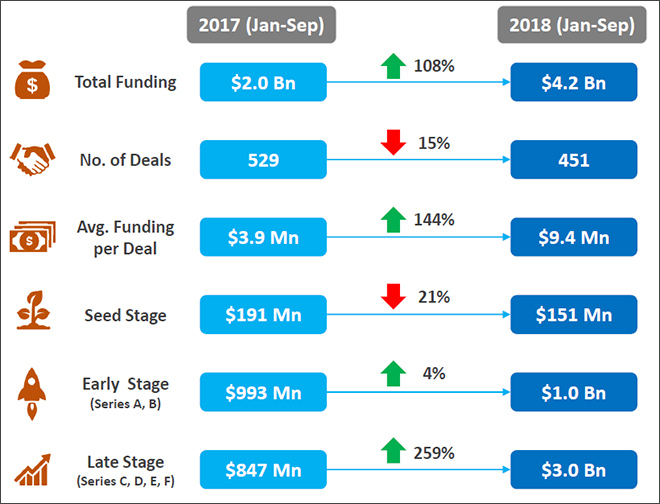

However, the funding pattern points towards other aspects of this growth. While total funding has gone up in 2018, the number of deals is down – implying bigger funding deals. Stage-wise funding pattern reveals that seed stage funding has marginally gone down and early stage funding experienced minimal growth, while late stage funding experienced more than 250 percent growth in 2018.

This clearly shows that there have been consolidations across the sector, and fewer established start-ups managed to grab a larger share of the funding. In terms of new employment generation, that may not be an ideal situation. However, there is no doubt that there has been a revival in the start-up growth story after a few jolts in previous couple of years.

| FIGURE 8: Tech Start-up Funding Overview |

|

|

* Funding details exclude debt financing and grants.

Source: NASSCOM-Zinnov Tech Startup Report, 2018 |

Why is then that the moderate success of Startup India is not talked about – even by the incumbent BJP? The answer probably lies in the limited employment generation capability of this new ecosystem. Total labour force of the tech start-ups is estimated to be at 0.17 million – compared to the CMIE-estimated job loss in 2018 at nearly 10 million across all sectors within the country.

There was also a re-launch of an older irrigation scheme in Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana, which also got a catchy tagline “more crop per drop”. This was important in reviving agricultural productivity, but it is now completely forgotten.

A few other macro policies were undertaken – out of which demonetisation is proven to be a disaster and GST has been mired in all kinds of implementation woes. But these four flagship schemes were meant to be the future direction of the economy towards generating growth and employment. However, in the transition from “Sabka Saath Sabka Vikas” to economically meaningless but politically loaded “Main Bhi Chowkidar” – unfortunately these flagships fell off the wheel. After five years, ideally these schemes should have been properly assessed, evaluated and re-calibrated for a sustainable macroeconomic recovery. Sadly, even the incumbent BJP stopped talking about these in the political slugfest of elections.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV