-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

As India’s economy urbanises, urban mobility is becoming ever more important. Does Hyperloop provide a solution?

If you have ever sat through afternoon gridlock, you will know the stress and exhaustion of congestion, and so does the economy. It is estimated that $22 billion is lost annually due to a lack of urban mobility across India’s top 4 metropolises alone. Lost time for workers, slowed deliveries, wasteful higher wages to compensate for endless commutes and inefficient matches between workers and employers all burden the urban economy. With India’s urban population expected to grow by 404 million people by 2050, and urban areas already contributing to two-thirds of India’s economic output, urban mobility must be central to the policy agenda. Transporting 23 million passengers and 3 million tonnes of freight between cities and across the nation every day, India’s rail system is key to solving the nation’s intercity mobility crisis. The overhaul of India’s railway systems, the launch of the “One Nation One Card” scheme, and the construction of India’s first bullet train between Ahmedabad and Mumbai are all promising steps forward. Albeit, the discussion has gone beyond the conventional, as state governments now look to the “next generation” of transport technology: Hyperloop.

Designed to move thousands of people per hour, Hyperloop pushes electromagnetically elevated pods through low air pressure tubes. By removing friction and air resistance, Hyperloop achieves speeds of up to 760mph, dwarfing India’s fastest train, the Gatiman Express, that has a top speed of just under 100mph. Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh have both undertaken feasibility studies to build Hyperloop systems, while Maharashtra has agreed to build a 15km test track with Virgin Hyperloop One (VHO) in December 2019 and has also opened a tendering process to global firms to build an operational 150km Hyperloop link connecting Mumbai to Pune by 2024.

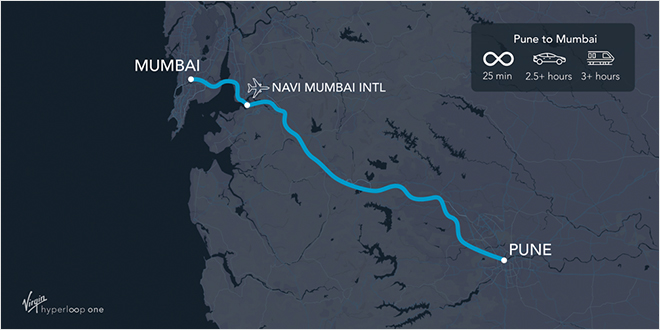

Currently, 130,000 vehicles make the two-and-a-half hour trip between Mumbai and Pune daily, which Hyperloop would reduce to just 25 minutes. The feasibility study of the Mumbai-Pune hyperloop estimates that the socio-economic benefits could amount to more than Rs. 300000 Crores which in over 30 years of operation could be reducing accidents and operating costs while integrating the two cities into one economic market.

Mumbai - Pune Hyperloop (Source: Virgin Hyperloop One)

Mumbai - Pune Hyperloop (Source: Virgin Hyperloop One)With a 25-minute commute between India’s financial centre and the ‘Oxford of the East’, Hyperloop has the potential to transform one of India’s most congested travel corridors. As Mumbai continuously struggles with congestion and expansion, individuals and firms could choose to live in Mumbai or Pune and commute effortlessly in-between, benefitting from what both cities have to offer along with a seamless connection to Navi Mumbai.

The final proposal for the Mumbai-Pune Hyperloop is soon to be submitted to the Maharashtra Infrastructure Development Enabling Authority committee, who will make the final decision. Before the decision is made, various difficulties around Hyperloop and its implementation have to be considered. The rest of this article will seek to explore the concerns under three main themes for implementing the Mumbai-Pune Hyperloop.

VHO will cover the initial bill of Rs 3000 crore million for the 15km test track, however, the cost of the 150km hyperloop link and who will pay for it is still unknown. Kaustubh Dhavse, an officer for the Chief Minister’s Office, has estimated it to be around Rs 100 – 170 Crores per km. This means that the estimated cost of the 150km route could range between Rs 15500 -25000 Crores.

In an interview, former Senior VP of Hyperloop One, Nick Earle revealed that a government subsidy will be required as the money collected from tickets “never pays” a public transportation system. Subsequently, one must consider as to how it must be considered how Maharashtra will raise the funds for this subsidy. Will it cut budgets elsewhere or take out a loan?

Loan consideration aside, any cost estimate for the Hyperloop should be treated with great caution.

Looking at previous infrastructure projects undertaken by Maharashtra, such as the Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet train, it would seem that a loan is a more likely choice. Granted that the state has a low debt to GDP ratio, there is room to manoeuvre in its finances, the source and terms of any loans taken out should however be carefully inspected to ensure public finances remain sound.

The on-going construction of Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet train loan bears an interest rate of 0.1%, repayable in 50-60 years with a 15-year lock-in period. A critical question that comes up is, whether this is an example of an ideal loan? Perhaps not when trends in exchange rates between the Indian Rupee and Japanese Yen are taken into consideration, it is important to also examine the fact that India may end up paying over Rs 300,000 crore for a loan of Rs 88,000 crores if the Rupee falls in value to the Japanese Yen. Consequently, it is imperative that the cost of any loan is fully calculated and not taken at face value.

Loan consideration aside, any cost estimate for the Hyperloop should be treated with great caution. A Hyperloop system stretching over tens of kilometres has never been attempted before. Elon Musk’s original estimate for a Hyperloop between L.A. and San Francisco was Rs 75 Crores per mile, although, in late 2016, internal documents from VHO revealed a significantly more expensive cost of Rs 800 Crores per mile for the same route. This is despite land prices, labour costs and engineering expenses being significantly cheaper in India, costs could soar well above original estimates. Accordingly, there needs to be a clear agreement whether the private or public sector will bear any increased costs in this public-private partnership.

Secondly, it must be affordable to the everyday user. If it is too expensive, the Hyperloop will be underused, leading to the expressways remaining congested, and the predicted benefits of Rs 300000 Crores will be a far-gone dream, thus defeating the purpose of the Hyperloop. So, the Maharashtra Government must study the tender offers and finance options to ensure this investment is affordable, effective and that they do not end up with an inflated bill.

Many large-scale transport infrastructure projects face issues around land acquisition, and the Mumbai-Pune Hyperloop will not be immune. To reduce land acquisition costs, the Mumbai-Pune Hyperloop will be partly elevated upon pylons, therefore not requiring huge parcels of land for rail tracks. Nevertheless, 109 objections were received regarding land acquisition during a one month period for citizens to submit suggestions and objections.

Objections and negotiations add to the monetary and time costs of development, as demonstrated by the Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet train project that has been a subject of protest by local farmers, who rejected the price-based “private negotiation” acquisition. The State Government should, therefore, be prepared to pay higher prices to compensate landowners or to ask for assistance from the Central Government to use The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation, Resettlement Act 2013, to purchase the land regardless of objection to ensure that it meets its 2024 deadline.

In order to test travelling with passengers, they have only reached speeds of under 300mph, much lower than the anticipated 760 mph. Questions around safety must be touched upon . A NASA report highlighted these concerns. For instance, if the inside of the Hyperloop pressure is operated at a near-vacuum, will the tube be strong enough to withstand the surrounding air pressure without scrunching? Will passengers be comfortable while being subjected to high g-forces?

Stretching over 150km and carrying thousands of passengers, a Hyperloop link would be extremely vulnerable to sabotage that could result in a high number of casualties.

In the case of power cuts and emergencies, would there be exits that users could use without coming into contact with the vacuum? Even with the possibility of the Mumbai-Pune Hyperloop being energy self-sufficient, powered by exterior solar panelling, it is still important to consider emergency exits, especially for security. Stretching over 150km and carrying thousands of passengers, a Hyperloop link would be extremely vulnerable to sabotage that could result in a high number of casualties. Hence, security agencies and forces must be consulted as to how feasible and practical it is to protect such a development.

Evidently, Hyperloop is not without technical doubts, and the principal scientific advisor of the central government has already been designated as the relevant authority to develop the safety standards for Hyperloop. If India chooses to lead on the international development of Hyperloop, it also chooses to assume responsibility of developing the correct safety procedures and legislation.

If Hyperloop was already developed, with no safety concerns, costs fully known and satisfactory financing options available, investing in a Mumbai-Pune Hyperloop would make perfect sense and would fundamentally improve intercity mobility in one of India’s most vital and congested travel corridors. Yet, this is not the case.

Innovation bears an element of risk and the potential for great returns. Hyperloop is no different, and India should not be blinded by its ambition. Upgrading current infrastructure, improving modes of existing public transport and the enforcement of traffic regulations are among many of the cost-effective and proven ways to relieve congestion and improve urban mobility. These guidelines should be remembered by the Maharashtra Infrastructure Development Enabling Authority committee as it makes its final decision on Hyperloop.

Article written by Matthew Coombes, Research Intern, Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.