-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

Western narratives on energy security that tend to exaggerate threats to scare the rest of the world into action are mostly about their interests. These cannot be substituted for our interests or global values.

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

In 1970, energy security was about oil supply security in North America and Western Europe. Political turmoil in the oil-producing countries in the Gulf region was the primary threat to energy security. That interpretation reined for over three decades as oil and geopolitics of the Gulf region continued to generate oil insecurity. The Arab oil embargo initiated in 1973 proceeded to redefine the United States(US) energy policy from one that managed abundance to one that managed scarcity. Three American Presidents and four Congresses struggled continuously from 1973 to 1980 to formulate an effective policy response to this single event. Soon after the embargo, oil prices increased threefold in the international market. The US government even considered seizing the oil fields in the Gulf region to secure supplies and rein in prices. Response of Western Europe closely followed US strategies. In 1974, the International Energy Agency (IEA) was jointly created by the US and its Western European allies for contingency oil-sharing arrangements (strategic reserves) and the exchange of information. Developing countries including India and China adopted Western ideas on energy security and pursued strategies of self-sufficiency or fuel autonomy, fuel efficiency, fuel diversity and security of sea lane supply to achieve what was then understood as ‘energy security’. Later the interpretation of energy security expanded geographically to include turmoil in other oil-producing countries in Africa and South America. The emphasis on oil supply security continued until oil demand started peaking and stagnating in OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries in the early 2000s. The emergence of the US as a net exporter of oil and gas in this period contributed to the decline in oil-centric energy security strategies.

Natural gas became the centre of attention in the context of energy security in the early 2000s because of the decline in domestic gas production in the US. The US Energy Policy 2001 called for improving ties with Russia, the largest source of natural gas exports. It observed that Russia held 33 percent of the world’s natural gas reserves and exported a full 35 per cent of its production to Europe and Central Asia. It argued that Russian natural gas exports can increase regional fuel diversification and advance environmental goals. It recommended discussions with Russia on energy and the investment climate in the country.

Institutional responses planned included making reliability standards mandatory and enforceable, with penalties for non-compliance, strengthening the institutional framework for reliability management in North America and increasing attention to physical and cyber security.

Electricity was brought within the purview of energy security following the power blackouts in North America in 2003. Institutional responses planned included making reliability standards mandatory and enforceable, with penalties for non-compliance, strengthening the institutional framework for reliability management in North America and increasing attention to physical and cyber security. Technological recommendations included power cables based on high-temperature superconductor (HTS) technology, a secure super-grid that would bolster transmission lines and would resist the stresses that can cause blackouts and combining an HTS super grid with a coast-to-coast hydrogen pipeline to supply fuel cells for cars and homes. Hurricanes and natural disasters were added to terrorism and turmoil as causes of energy insecurity after hurricanes Katrina and Rita destroyed vital energy infrastructure in the US. In the 2010s, energy ‘demand’ from developing countries was interpreted as a threat to the energy security of developed countries. Developing countries in general and India and China in particular were labelled as countries making undue claims on the world’s energy resources. The ‘insatiable appetite’ for energy of the average Indian who consumed a small fraction of energy that an average American consumed was among the perceived threats to energy security that would supposedly deplete oil reserves and destroy the environment. State-owned Chinese companies were anticipated to prop up repressive regimes in their pursuit of oil. In 2012, President Obama blamed oil demand from China and India for an increase in global crude oil prices. The IEA warned that demand for oil imports by China and India would quadruple by 2030 and could create a supply “crunch” as soon as 2015 if oil producers do not step up production, energy efficiency fails to improve and demand from the two countries is not dampened.

The ‘insatiable appetite’ for energy of the average Indian who consumed a small fraction of energy that an average American consumed was among the perceived threats to energy security that would supposedly deplete oil reserves and destroy the environment.

From the beginning of the 2020s, old notions of energy security that blamed import dependence as the source of insecurity have been revived by the war in Ukraine and China’s dominance in the critical mineral value chain. Responding to the surge in natural gas prices following the war in Ukraine, the European Union (EU) called for energy dependence on Russia to be significantly reduced and for an 'immediate full embargo' on imports of oil, coal, nuclear fuel and gas from Russia, as well as the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines to be 'completely abandoned'. The EU’s REPowerEU plan embarked on a strategy of diversifying energy supplies, increasing gas storage, speeding up the deployment of renewables, completing the necessary gas and electricity interconnections, and improving energy efficiency. The most important response to China’s dominance over critical mineral supply chains recommended by the US and other advanced countries is supply chain nationalism which calls for control over supply chains. Several terms including but not limited to self-sufficiency, friend shoring, “just in case” supply strategies and de-risking supply chains that essentially call for supply chain sovereignty are repeated in all reports and platforms discussing the threats to the clean energy transition.

In the last five decades, energy security problems have been framed with Western concerns and interests in mind. The Rest of the World has blindly followed these strategies though their energy problems were completely different. The Rest of the World gathers the institutional and material resources to pursue Western energy security strategies only to find that the West has moved on to other interests. Take the case of ownership of equity oil resources. In the 1970s the US had geo-political power over oil-exporting countries in the Gulf region even though all US oil companies that operated in these countries were privately owned. Taking a cue from the US on ownership and control of energy assets, China and India whose oil demand took off only at the turn of the century pushed State-controlled companies to invest in oil equity assets around the World. This neither proved to be a hedge against high oil prices nor a source of supply security. Oil supply security did not become a sustained concern as it was made out to be. In the end, China and India may be holding what may eventually become sub-prime assets. The same is true in the case of natural gas. In the late 2000s, Russia, Iran and Qatar which controlled over half of the world's natural gas resources were expected to form a geopolitical axis and gas cartel that would threaten global stability. Shale gas production in the US wiped out that threat without a trace. The rest of the world is now much bigger than the West not only in terms of population numbers but also in terms of the size of their economies, quantum of energy consumption and geopolitical weight. But this status arises from quantity at the aggregate level. Quality at the individual level remains low as the Rest of the world is mostly poor. For most of the rest of the world, energy affordability and energy poverty are as important as supply security if not more. Western narratives on energy security that tend to exaggerate threats to scare the rest of the world into action are mostly about their interests. These cannot be substituted for our interests or global values.

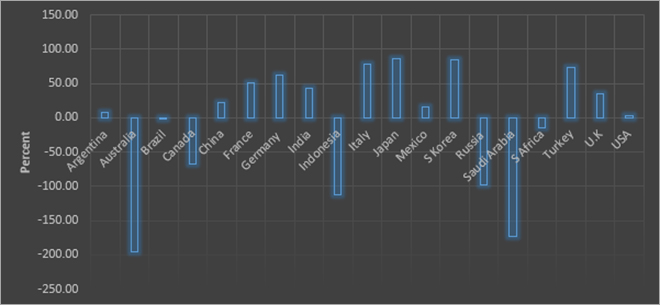

Source: International Energy Agency for Imports & BP Statistical Review of World Energy for Consumption

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation. Akhilesh Sati is a Program Manager at the Observer Research Foundation. Vinod Kumar Tomar is a Assistant Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Ms Powell has been with the ORF Centre for Resources Management for over eight years working on policy issues in Energy and Climate Change. Her ...

Read More +

Akhilesh Sati is a Programme Manager working under ORFs Energy Initiative for more than fifteen years. With Statistics as academic background his core area of ...

Read More +

Vinod Kumar, Assistant Manager, Energy and Climate Change Content Development of the Energy News Monitor Energy and Climate Change. Member of the Energy News Monitor production ...

Read More +