-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

India needs an urgent overhaul of its urban governance architecture to improve the performance of the cities as potential engines of growth for the national economy

Image Source: Getty

India stands at the threshold of a surge in urban population over the next two decades. The influx of people into Indian cities is projected to exceed the current urban population, possibly reaching 900 million by 2050. With more than 50 percent of the country’s population expected to turn ‘urban’ by the middle of the 21st century, the policy and planning needle are being pushed from predominantly rural to urban landscapes.

However, an analysis of rural and urban areas on the indicators of employment generation potential and contribution to the country’s GDP reflects an imbalance. For example, agriculture, a predominantly rural activity, employs more than 45 percent of the total workforce but contributes a mere 18 percent to the gross value added (GVA). On the other hand, the industry and service sectors, which mainly function in and around cities, contribute more than 80 percent to India’s GVA while employing nearly 55 percent of the workforce. While the share of agriculture in India’s economic growth has declined, its employment generation value remains significant.

The industry and service sectors, which mainly function in and around cities, contribute more than 80 percent to India’s GVA while employing nearly 55 percent of the workforce.

To correct this contradiction, India needs to work towards urban ecosystems that enhance its growth momentum and offer more productive employment opportunities. This will involve the substantive financial empowerment and decision-making autonomy of urban local bodies (ULBs), which were officially recognised by the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act (CAA), 1992 as the “third tier of governance”. However, three decades after the CAA mandated decentralised governance, cities remain under state domination.

Urban development is a state subject under the Constitution of India, and ULBs have historically remained under the absolute financial and functional control of the states. The CAA was the first comprehensive attempt to democratise and decentralise ULBs by empowering them with autonomous status. Before the CAA, states could extend the stipulated term of ULBs or arbitrarily invalidate them, primarily if the ULBs’ political predisposition differed from that of the state government. In an attempt to reduce ULBs’ financial dependence on the state, the CAA also formalised the appointment of State Finance Commissions (SFCs) to recommend the devolution of funds from the state to the ULBs.7

The CAA was the first comprehensive attempt to democratise and decentralise ULBs by empowering them with autonomous status.

The CAA paved the way for the Government of India (GoI) to pay closer attention to cities. The Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM), launched in 2005, promised central funds for city infrastructure and service enhancement against specific reforms carried out by states and ULBs. JNNURM asserted urban reforms by incentivising states and cities. The following year, GoI introduced the National Urban Transport Policy, which focused on urban mobility by prioritising “moving people” over “moving vehicles”. Another significant attempt at urban transformation came in 2015 with the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) and its sub-missions.

Despite its intended objectives to liberate local bodies from indiscriminate state control, the CAA struggled to yield tangible change. Several of its mandates, including financial autonomy and the term and executive powers of the mayor and the local elected representatives, were discretionary, allowing states to continue their hold over ULBs. Cities remain under the control of state-appointed commissioners, whereas mayors fill ceremonial positions with no legislative powers.

Cities remain under the control of state-appointed commissioners, whereas mayors fill ceremonial positions with no legislative powers.

Overlapping Functional Constraints

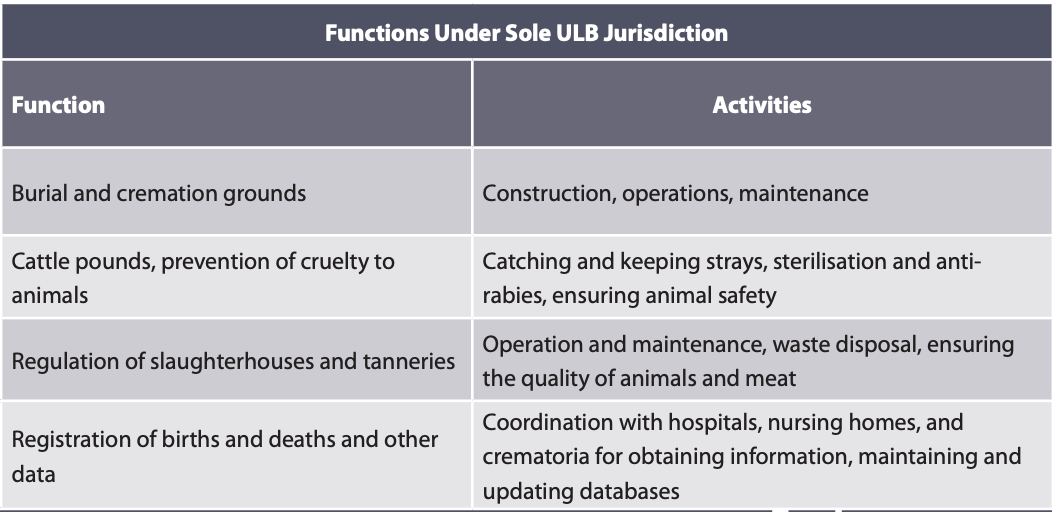

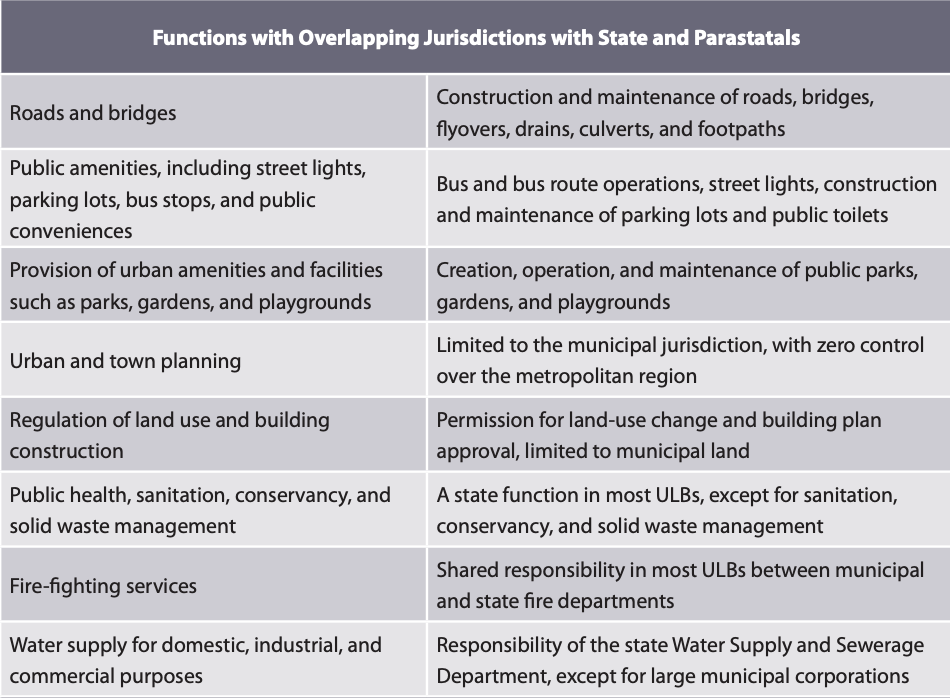

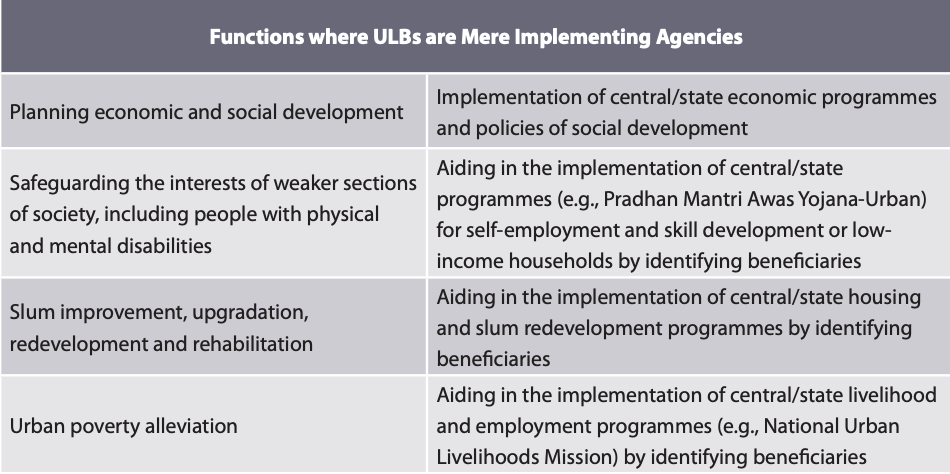

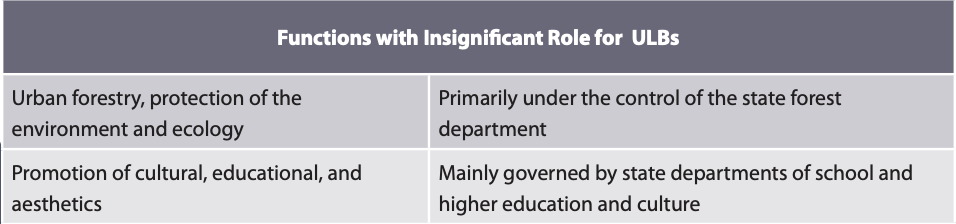

While the CAA’s Twelfth Schedule delineated 18 municipal functions that states must devolve to the ULBs (see Table 1), these functions are constrained by the overlapping mandates with state-established parastatals.

Table 1: ULBs’ Overlapping Mandates with States and Parastatals

Source: Compiled by the author from the Comptroller and Auditor General of India Audit Report 2022

Due to ambiguities in the CAA, states could choose which functions they wanted devolved to the ULBs. While large municipal corporations such as Mumbai perform nearly all the 18 functions, albeit with jurisdictional and functional overlaps with state and parastatals, smaller ULBs continue to play a subordinate role in critical aspects of city governance and administration. India’s Comptroller and Auditor General’s 2002 audit report for ULB empowerment in Haryana highlights that, of the 18 functions highlighted in the CAA, ULBs were solely responsible for only four. The ULBs had overlapping mandates with the state and parastatals for eight functions, performed “implementation agency” roles in four, and had “insignificant roles” in two.

Worsening Financial Health

Notwithstanding the CAA’s discretionary provisions to lend financial autonomy to ULBs through the levy and collection of taxes, duties, tolls, and user charges, as well as grants-in-aid from the state’s Consolidated Fund, ULBs across India remain cash-starved, witnessing a growing gap between their functions and available financial resources. The recommendations made by the SFCs regarding ULBs’ financial empowerment by states have received superficial recognition, prompting the Reserve Bank of India to observe that “the process of devolving funds to local bodies on the recommendations of SFCs is not working efficiently.”

Additionally, the CAA overlooked an archaic constitutional provision, which grants the GoI properties exemption from ULB taxes under Article 285. Properties owned by the state also enjoy arbitrary tax exemptions and service-charge subsidies. For example, the Maharashtra government owes INR10.95 billion in stamp duties to the Pune Municipal Corporation. The bungalows used by ministers and senior bureaucrats in Mumbai have an outstanding payment of INR 9.5 million in water bills to the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation. The Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation has outstanding bills of INR 3.25 billion payable by the Western Railway and multiple state utilities. Likewise, government offices in Bhubaneswar owe INR 300 million in property tax to the city municipal corporation. The Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation seeks to recover over INR 20 billion in property tax from central government- and state-occupied buildings.

The CAA overlooked an archaic constitutional provision, which grants the GoI properties exemption from ULB taxes under Article 285.

In addition to the CAA’s failure to address the fiscal imbalance, stopping short of establishing an independent tax framework for ULBs, the imposition of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017, which subsumed nearly all local taxes, including octroi and entry tax, further crippled the financial health of cities. A 2019 study of the financial health of municipal corporations of metropolitan regions found that their total revenues dipped as a percentage of GDP from 0.49 percent in 2012-13 to 0.45 percent in 2017-18, just one year after GST implementation. Consequently, cash-starved cities now face an even larger unfunded mandate. Ironically, many state governments are resorting to populist measures such as property tax exemptions, which is the biggest ULB revenue earner, after the abolition of the octroi, thus increasing their financial distress.

Dysfunctional Urban Planning Function

Most states exercise discretion by not bringing specific amendments to their respective Town and Country Planning Acts to devolve the “urban planning, including town planning” function to the ULBs, as mentioned in the CAA’s Twelfth Schedule. Even the few states that have recognised the planning function of ULBs continue to wield their “approval” authority to City Development Plans. They often enforce politically expedient changes in land-use reservations, leading to delays in their implementation.

India needs an urgent overhaul of its urban governance architecture to improve the performance of the cities as potential engines of growth for the national economy. Genuine self-governance of ULBs demands a paradigm and attitude shift on the part of states, which must provide strategic guidance for accelerating urbanisation and give up all functional and operational control. Well-defined, autonomous, independent functional and financial powers of ULBs, led by empowered mayors as chief executives who are answerable to the city electorate, in line with principles of subsidiarity and decentralisation, are imperative for India’s urban future.

India needs an urgent overhaul of its urban governance architecture to improve the performance of the cities as potential engines of growth for the national economy.

The failure of the CAA to shepherd such top-down transformation calls for the GoI to contemplate second-generation urban reforms in the context of the current and emerging urban landscape and the critical role of cities in national economic growth. India needs sharper and more binding constitutional amendments that can ensure that states accord better treatment to the third tier of governance and effectively emancipate ULBs in India’s Amrut Kaal.

Dhaval Desai is a Senior Fellow and Vice President at the Observer Research Foundation

This essay is part of a larger compendium “Policy and Institutional Imperatives for India’s Urban Renaissance”.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Dhaval is Senior Fellow and Vice President at Observer Research Foundation, Mumbai. His spectrum of work covers diverse topics ranging from urban renewal to international ...

Read More +