This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

The Electricity (Amendment) Bill, 2022 (EA2022) was introduced in Lok Sabha (lower house of the Parliament) on 8 August 2022. The

Bill amends the Electricity Act, 2003 (EA2003) which regulates the electricity sector in India. EA2022 was later referred to the

parliamentary standing committee on energy after members of several opposition parties opposed its introduction in the Lok Sabha because it

violated the federal principles of the constitution. EA2022 is also

opposed by farmers as they fear that it will eliminate subsidised access to electricity and by some

trade unions who fear job losses after a takeover by corporates favoured by the government.

Electricity Amendment Bill

The subject of electricity is placed under the

concurrent list (responsibility shared between the Centre and states) of the Indian constitution and the distribution of electricity is completely under the state government through state electricity boards SEBs (State Electricity Boards are now recast as discoms). The concern expressed by opposition parties is that EA2022 seeks to amend the

constitution through a statute that allows the central government to appropriate powers of the state government.

EA2022 is also opposed by farmers as they fear that it will eliminate subsidised access to electricity and by some trade unions who fear job losses after a takeover by corporates favoured by the government.

EA2022 seeks to amend Section 42 of EA2003 to facilitate

non-discriminatory open access to the distribution network of a distribution licensee. Earlier, the government was hesitant to privatise distribution as it would have deprived them of a

potent tool of patronage. Now, however, governments

crave the patronage of corporates rather than the patronage of the poor as corporate money and media channels they control can achieve the same electoral outcomes.

In theory, open access would allow the entry of multiple companies to supply electricity to consumers as in the case of mobile telephone services. This amendment has caught the attention of the middle and affluent classes eager to

replace state suppliers with efficient private suppliers. The concern over this provision from state governments is that it will allow the central government to grant multi-state entry of

favoured corporates into the electricity distribution segment. The EA2022 achieves this by

blurring the distinction between the distribution licensee and the distribution company. This means that any company will only require to register to trade in electricity to enter the distribution segment. In contrast, a distribution licensee will have to go through

due diligence by the state electricity regulatory commission (SERC) to distribute electricity in a particular area. Multiple operators in areas where there are several categories of consumers with different tariff slabs will create complex administrative and economic challenges. EA2022 offers

open access at the low-tension consumer level. In theory, this could mean that a distribution company can choose to supply electricity to urban areas

concentrated with affluent households marginalising areas with poor and low-income households. This would effectively create two different market segments, one, high-cost good quality commercial power for the cities and another, low-cost, poor-quality social electricity for rural areas supplied by discoms.

As per EA2022,

SERCs can fix the minimum and maximum ceiling of tariff for the sale or purchase of electricity in case of a shortage of supply. This will go against multiyear tariff orders that have been issued to limit volatility in electricity tariffs.

Harsh penalties are imposed by the EA2022 on discoms for

non-compliance with renewable power purchase obligations (RPOs) as prescribed by the central government. This along with the

“must-run” status for renewable power (RE) will ease the evacuation of power generated by large corporate solar plants even when there is no demand for additional electricity supply. This is equivalent to a “take-or-pay” contract arrangement that could add to the

strain of financially challenged discoms.

Multiple operators in areas where there are several categories of consumers with different tariff slabs will create complex administrative and economic challenges.

EA2022 expects central

electricity regulatory commissions (CERCs) to effectively carry out policies of the central government which can compromise the autonomous functioning of a regulatory body. It can also effectively make SERCs redundant. This presumably follows from a

Niti Aayog report on distribution reforms that recommended the creation of regional electricity regulatory commissions with participation from the central government above state electricity regulatory authorities to limit political interference in regulatory functions.

Sequencing of reform initiatives

Electricity generation was open to the private sector after EA2003. The private sector now accounts for

39 percent of power generation capacity compared to

21 percent for the central sector and

24 percent for the state sector. The EA2022 provides for privatisation of distribution and to a lesser extent competition and regulation, but these must be introduced in a phased manner and more importantly in the

right sequence. Most studies suggest that establishing regulatory infrastructure, and introducing competition should precede privatisation.

Electricity distribution is a

network infrastructure industry that has traditionally been viewed as a strategically important activity with

‘natural monopoly’ characteristics. This justified state ownership through SEBs. Economic, institutional, and technological developments have reduced the benefits of economies of scale justifying introducing competition to SEBs. But SEBs are not inefficient commercial entities as often portrayed.

According to Ruet, SEBs are not inefficient enterprises but administrations whose nature was to pursue objectives that were heterogeneous and so, irreconcilable to judgement by sole economic criteria.

Joel Ruet, a French economist who studied the Indian power sector in the early 2000s observed that if socialism was “Soviets plus electricity”, according to Lenin, independent India was to a great extent “democracy plus state electricity boards”. According to Ruet,

SEBs are not inefficient enterprises but administrations whose nature was to pursue objectives that were heterogeneous and so, irreconcilable to judgement by sole economic criteria. Ruet’s observation captures the important role SEBs played, in mediating the provision of electricity to consumers initially as an instrument of development policy (

expansion of agricultural irrigation and later village electrification) but eventually as a lever to achieve political objectives (subsidised or free access to electricity offered before elections). India today has almost

complete coverage of the electricity network that was achieved in most other countries only at higher income levels. The problem of the electricity distribution sector is, however, framed as one of SEB or discom inefficiency and this justifies privatisation of the distribution segment. SEBs, now unbundled and recast as discoms continue to be instruments to meet political ends. This has limited the ability of

electricity tariffs to reflect the true cost of supplying electricity which is among the most important reasons for discom woes. The upside of tariff concessions announced by political parties accrues to the party in the form of electoral gains while the downside is passed on to discoms that grapple with mounting losses and a C rating.

Studies have shown that privatisation, competition, and regulation, though desirable, do not yield these results

if they are implemented simultaneously. Both theoretical and empirical works have pointed to the importance of competition in raising economic efficiency when privatisation occurs. According to

Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel prize winning economist, successful economic programs require extreme care in sequencing the order in which reforms occur. Recent empirical research on reform in developing countries has concluded in favour of gradualism, which emphasised the importance of first establishing institutional

infrastructures conducive to market forces, including setting up of competitive industrial structures and appropriate regulatory systems. A study based on a panel dataset covering

25 developing countries for the period 1981 to 2001 found that establishing an independent regulatory authority and introducing competition before privatisation was correlated with higher electricity generation, higher generation capacity and improved capital utilisation. An earlier study that used a larger data set involving

51 developing countries, over the period from 1985 to 2000, found that competition was more important than privatisation in raising economic performance in electricity generation.

Evidence from industrialised Western economies, including the UK, shows that privatisation alone is insufficient to stimulate performance improvement, especially in public utilities with natural monopoly characteristics.

Recent empirical research on reform in developing countries has concluded in favour of gradualism, which emphasised the importance of first establishing institutional infrastructures conducive to market forces, including setting up of competitive industrial structures and appropriate regulatory systems.

Compared to the speed of privatisation in the electricity sector in India (in generation after EA2003) the process of establishing a strong autonomous regulatory regime has been slower. Though regulatory bodies have been established (CERC, SERC) they are “captured” by the government and by corporates through the government. Privatisation as reflected in EA2022 could mean more of the same as privatisation is framed as the end rather than the means for creating an efficient and affordable electricity network. For reform of the distribution sector to be

transformative, fair, and equitable, the government should first ensure that tariff reform takes place with subsidies transferred directly to the beneficiary. Second, the government should ensure that regulatory bodies are truly autonomous. Third, the government should break up discoms and allow them to compete against each other to improve discom performance and introduce competition. Privatisation should follow only when these measures succeed.

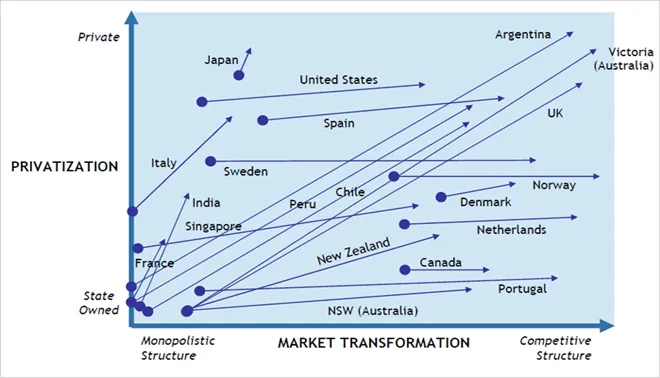

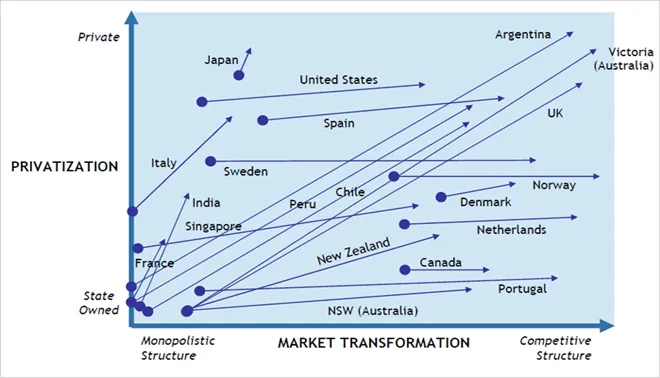

Privatisation Versus Market Transformation in the Electricity Sector

Source: World Bank

Source: World Bank

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV