This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

This article is part of the series Comprehensive Energy Monitor: India and the World

Background

At the time of India’s independence (1947) electricity generation and distribution were primarily in

the hands of the private sector. Private companies and their franchisees focused on urban and industrial demand which gave them a reasonable return on investment. Rural and agricultural sectors were ignored as they were seen as unprofitable.

Only one in 200 villages was electrified and just 3 percent of the population in six large towns consumed over 56 per cent of utility electricity.

Over 506 of 856 towns with more than 10,000 people were not electrified. The per person electricity consumption was 14 kWh per year and in many states, the per-person consumption was as low as 1 kWh per year. The first government of independent India saw this as “market failure” to provide equitable access to electricity and decided to take charge.

Electricity is a

concurrent subject as per the Constitution which meant that both the State and Central governments could shape electricity sector policy. But the setting up of

State Electricity Boards (SEBs) under the Electricity Act 1948 as vertically integrated monopolies gave state governments greater control of electricity generation, transmission, and distribution. Under SEB governance electricity access increased rapidly to cover most villages but SEB finances deteriorated. In the 1990s, state governments were forced to concede control over discoms to market forces with reforms initiated by

development funding agencies such as the World Bank. The thrust was for unbundling of the electricity sector into distinct activities of generation, transmission and distribution that would operate on commercial terms. The enactment of the

Electricity Act 2003 (EA 2003) further eroded the power of state governments over discoms as it pushed discoms towards commercial and market discipline.

Now the pendulum of electricity distribution is swinging back to private sector control. Legislative push in the last decade (for example the

draft Electricity Amendment Act 2014 and its many revised and updated versions) is focused on delicensing discoms to give a greater role to the private sector in distributing electricity. The justification is that

multiple players in electricity distribution in a given area will promote competition, substantially improve efficiency in operations and give

consumers choice in terms of suppliers and also in terms of fuels (fossil and non-fossil fuel-based electricity). The models of privatisation such as franchising that were abandoned more than seven decades ago are returning to the discussion tables of think tanks. The question of whether private actors will cherry-pick lucrative industrial and affluent consumers and ignore the rest is being debated. There is hope in some quarters that the private sector will promote supply and demand for green electricity. While there is a possibility that economic efficiency and service delivery may improve with the participation of the private sector, it may not make a significant difference to India’s environmental goal of decarbonising the grid and social goal of improving electricity access.

Decarbonising the Grid

India’s

updated nationally determined contribution (NDC) contained two energy-related quantitative commitments. First to reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP (gross domestic product) by 45 percent by 2030, from its 2005 level and second to achieve about 50 percent cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030, with the help of the transfer of technology and low-cost international finance, including from Green Climate Fund (GCF). Efforts to realise these commitments will complement the domestic target of

having 500 GW (gigawatts) of renewable energy (RE) capacity by 2030. These mandates along with Government incentives that include but not limited to capital, cheaper credit, priority access to transmission,

‘must-run’ status, feed-in-tariff and waiver of interstate transmission fee have created a profitable business model for private players that guarantees despatch of RE electricity and cost recovery through stable tariff over several decades. Not surprisingly the

private sector accounts for 95 percent of installed RE power generation capacity. While the private sector is dominant in the supply of RE electricity, they may not necessarily facilitate consumer uptake of RE electricity as discoms franchisees or licensees.

Today the system level costs of accommodating intermittent

RE electricity are socialised. The existing grid that is powered mostly by thermal (coal and natural gas) power generation provides the back-up to make up for RE intermittency. The

cost of maintaining back-up and related costs such as the cost of rapid depreciation of thermal power generation assets because of frequent ramping up and down to make up for RE intermittency are passed on to electricity rate payers and tax payers. Private Discom operators may not significantly deviate from this set-up. The political economy of India shaped by a large number of voters with low purchasing power is likely to favour fossil-fuel based electricity,

especially domestic coal-based electricity. The draft national energy policy released in 2017 observed that Discoms cannot be burdened with the

social and system cost of accommodating RE electricity and recommended finding alternative mechanisms for meeting additional costs. This is true irrespective of whether the Discom is publicly or privately owned.

Electricity Access

In 2014, when the current government came to power,

94 per cent of the villages were ‘electrified’ and the per person electricity consumption was just over 1000 kWh. This signified substantial improvement in providing electricity access to households but the impressive numbers concealed widespread inadequacies.

Supply of electricity to grid connected rural households averaged only about a few hours a day. The per person figures for electricity consumption is a statistical artifact under which all available electricity is distributed equally to over 1.3 billion people. The average hides huge inequalities between different states, between urban and rural areas and between affluent and poor households. If total electricity consumption by the domestic sector alone is distributed equally among the population per person availability of electricity

falls to just over 220 kWh which is the line for energy poverty. In 2014, 90 percent of rural households consumed less than 100 kWh of electricity per month while

50 percent of the rural households consumed less than 50 kWh of electricity per month.

In 2019, the government claimed that 99 percent of the households were electrified but this claim was not backed with credible data. In 2020, Niti Aayog revised the claim stating that

99 percent of “willing” households have been electrified. The most probable interpretation of the term “willing” is a market oriented one where it is taken to mean

“willingness to pay” for access to electricity. If true, this could be a sign of things to come when electricity distribution is privatised. Labelling those who are “unable” to pay as those who are “unwilling” to pay, is a clever way of side-stepping the social goal of providing electricity access.

All electricity access initiatives in India aim to

provide a physical connection between the village (or house) and the grid, side-step the persistent challenge of low demand for electricity (economic scarcity arising from low affordability) from poor households. Low demand for electricity from rural households is the consequence rather than the cause of economic scarcity (or poverty). Low density of households and low consumption levels increase the cost of providing electricity access and are revenue negative for Discoms. This is an important factor behind the evolutionary rather than revolutionary pace of increasing electricity consumption. The private sector is not likely to radically change status quo.

Universal service obligation is often cited as remedy for cherry picking of consumers by private operators but as the telecommunication sector clearly illustrates, private players will find a way to work around it. As the French economist Joel Ruet elegantly put it, “

power cuts will be privatised”.

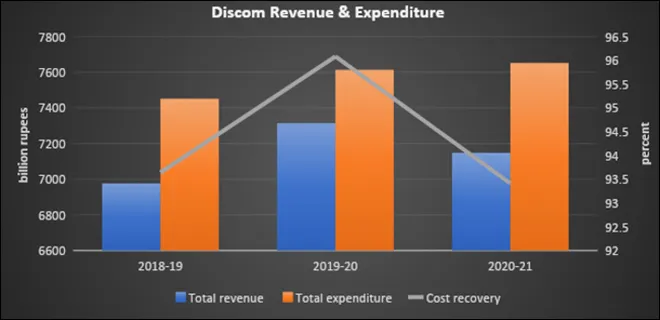

Source: Power Finance Corporation

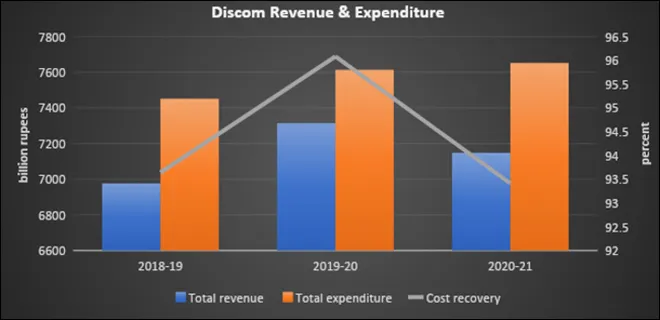

Source: Power Finance Corporation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

This article is part of the series

This article is part of the series

PREV

PREV