-

CENTRES

Progammes & Centres

Location

There is possibility of active policy interventions. What is needed is international collaboration with an aim to achieve development goals.

This article is part of the new publication — Reconciling India’s Climate and Industrial Targets: A Policy Roadmap.

Efforts towards a transition to low-carbon energy are gaining pace across the world. India, for example, has been making significant progress in increasing the share of renewable energy in its total energy mix. Among the drivers of the ongoing transition is the commitment of the business sector to step up on its shift to clean energy. After all, the corporate sector makes up about 25 percent of total energy demand in the country and their policies are key to building a low-carbon economy. Certain companies have voluntarily adopted a target of 100-percent renewable energy within a specific period, also known as the RE100 initiative.<1> Globally, there was a 40-percent rise in clean electricity purchases in 2019.<2>

The rise in demand for renewable energy also provides benefits in increasing the manufacturing base, creating job opportunities, and diversifying the export market. In turn, opportunities in manufacturing can help the export sector through greater integration into global value chains and by enhancing India’s trade potential in the wind and solar energy sectors. India has had limited success so far in developing indigenous capacity in the solar sector. It is possible to attain security in these sectors by identifying the obstacles and having a more focused policy approach. India also needs to identify manufacturing opportunities in new technology areas such as hydrogen fuels, and devise long-term strategies accordingly.

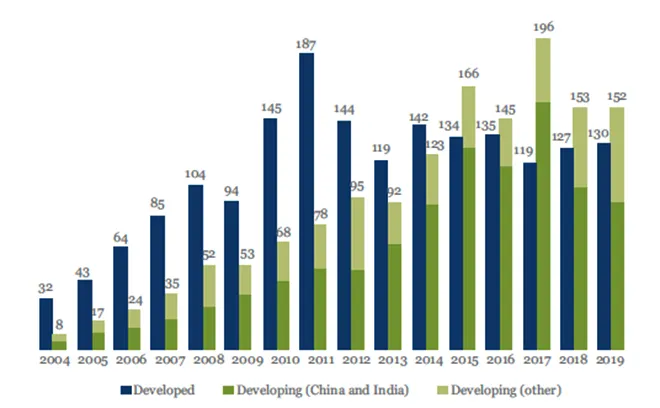

Developing the renewable manufacturing base will help attract investments. Globally, investments in renewable energy in developing countries reached US$ 152.2 billion in 2019. Since 2010, investments in the developing world, which constitutes 54 percent of the global total, have exceeded investments in developed economies (See Figure 1).<3>

Figure 1. Investments in Renewable Energy Sector (US$ Billion)

Source: UNEP-Bloomberg report, 2020<4>

Source: UNEP-Bloomberg report, 2020<4>

The rest of this chapter identifies current issues in the domestic production supply chain of clean energy sources and suggests possible policy initiatives. The analysis also delves into the issue of transfer of technology at the global level, and the leading role that India can play to facilitate technology transfer and development of green technology.

India’s wind energy industry is relatively self-sufficient, with 80 percent of equipment produced domestically. India today is the world’s fourth largest producer of wind energy, with installed capacity at 37 GW.<5> The industry is wholly private owned.<6> Figure 2 shows the supply chain for the wind energy sector. There are fewer players in certain segments of the supply chain — the gearbox, bearings, and blades — as they require high investments and have considerable barriers to entry. Other segments such as generators and tower segments have lower barriers to entry, and thus have more players. There are enormous opportunities for manufacturing at the various stages of the supply chain — from raw material to component suppliers. There is also opportunity for service providers in operations and maintenance, feasibility studies, and geotechnical services.

Figure 2. Supply Chain in the Wind Energy Sector

India’s wind energy sector currently caters to small turbines with capacity between 250kW to 1.8MW. The larger equipment are supplied by wholly Indian-owned Suzlon,<7> which is one of the largest companies in the world in wind turbine manufacturing. It supplies about 50 percent of wind turbines in India and has 8 percent of the global share.<8>

Favourable national-level policies have helped create a stable regulatory environment for the wind energy sector. The government has encouraged domestic production with suitable domestic pricing policies and by adjusting customs duties. It has launched initiatives such as Generation Based Incentive (GBI) schemes, the accelerated depreciation scheme, as well as feed-in tariffs.<9> The latter provides a guaranteed purchase price, lowering the risk for suppliers.

In 2017, the government replaced the system of feed-in tariffs with tariff-based competitive auctions on account of growing capacity and fall in the prices of renewable energy.<10> This model has also been adopted at the state level. While competition from auctions has led to a fall in tariffs, it is likely to affect revenue as well, making manufacturers wary about the system.<11>

What helped Suzlon attain the global status that it has reached? Suzlon initially acquired basic technology through technical collaborations with German companies and through licensing, before developing its own research centres. Local manufacturing allowed the company to produce at competitive prices due to lower costs of labour and other inputs. The strategy of Suzlon to have an integrated supply chain meant that it had more control over cost across the entire supply chain, and the flexibility to respond to demand. Other factors that contributed to the initial success of Suzlon include R&D, and effective supply chain management.

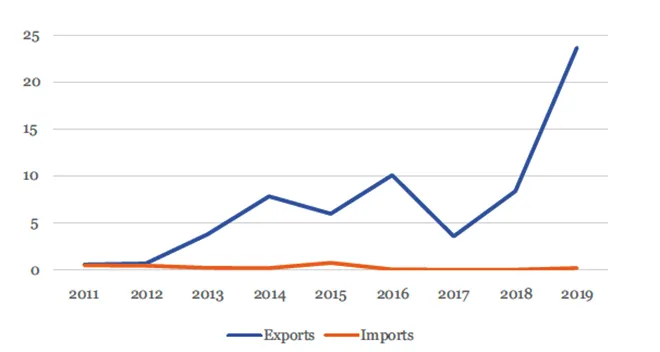

Figure 3 shows that in the trade of wind turbines, exports — which reached US$ 23.6 million in 2019 — far exceed imports, at less than 0.2 million the same year. This shows that India has the potential to become an export hub in the wind energy export sector.

Figure 3. Imports and Exports of Wind Turbine (HS Code 84128030) (US$ million)

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry<12>

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry<12>

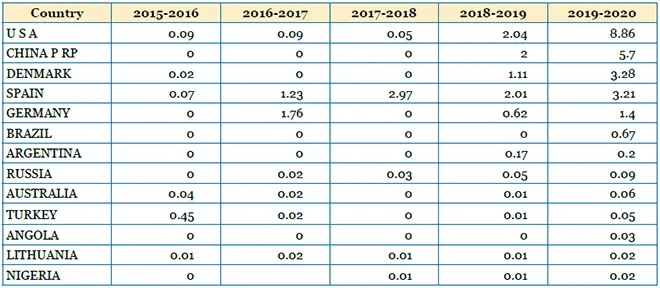

Table 1. India’s Exports of Wind Turbine (by Country, in US$ Million)

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry<13>

Source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry<13>

As Table 1 shows, exports to Latin American countries such as Brazil and Argentina have increased, along with those to African countries. In 2011, officials from Uruguay conducted visits to India to explore collaboration in the wind energy sector.<14> Industry experts agree that India can become a key supplier to the growing markets of Africa and Latin America. This will give India the opportunity to diversify its export basket and expand their reach. Another opportunity is in exporting older and lower-capacity turbines, refurbished at competitive prices, to countries looking to expand their renewable energy base. Increasing exports from the sector would also help reduce the current account deficit and balance the huge import bills on oil imports.

Indeed, the wind energy sector is fairly well established. Indian companies have acquired licenses from foreign companies for technology and have also shown the ability for research and adapting technology to domestic conditions. However, India needs more investments in design and research comparable to those of companies abroad. New renewable energy technologies require huge investments, and the role of government facilitation is important. China, for example, has specific funds for expenditure on R&D in wind turbine systems.<15> The capacity of Chinese wind turbines has increased from 600 kW in 1997 to 6 MW by 2011. Research for designed 10-MW wind turbines is being undertaken by many Chinese companies. In its 13th five-year plan, China identifies technology between 8-10 MW as the next step in the country’s technological upgrade.<16> Globally, turbine sizes have reached the size of 14 MW.<17> India requires long-term strategic planning to develop technologies and identify specific ones that will increase and diversify the export basket.

The next step would be to move into offshore wind production, which is well developed in Europe. India has a draft policy as of 2013. The off-shore wind sector has higher costs for logistics, and greater technology challenges than on-shore. Especially with respect to infrastructure, the sector faces challenges in the transportation of components. India’s logistics cost, which is at 14 percent of GDP, needs to be brought down to below-10 percent of GDP, which is comparable to that of developed countries.<18> The high cost of export credit is a significant cost concern, with foreign and rupee export credit interest rates at more than 4 percent and 8 percent, respectively. Globally, the rates are at 0.25-2 percent.<19> Given the level of development of the wind energy sector, India’s EXIM bank should extend long-term credit to the sector for periods of 10-15 years.

The solar sector industry is dominated by Chinese and western companies, but Indian companies such as Adani, Jupiter, and Tata, are also making a mark.<20> Eighty percent of solar cells and modules in India are imported from China. Indian modules are 33 percent more expensive than the Chinese ones.<21> The solar industry has been dependent on imports of critical raw materials such as EVA, back-sheet, reflective glass, balance of system for solar thermal, and PV. In addition to higher costs, the Indian solar energy sector suffers from underutilisation of current production capacity, due to cheaper Chinese products.

The development of indigenous capacity for manufacturing solar energy can create jobs in engineering, construction, maintenance, finance, design, and wholesale distribution. A study by Shakti Foundation on India shows that a 3-GW integrated manufacturing plant (polysilicon to solar module) can generate some 5,500 jobs.<22> The current domestic manufacturing capacities of solar cells and modules is about 3 GW and 10 GW, respectively, as of 2019, whereas the demand is 20-30 GW per year. The difference is filled by imports.<23>

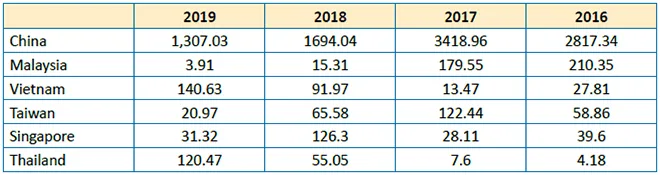

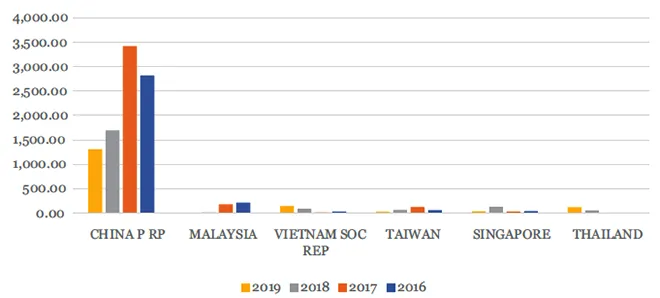

Table 2 shows the top sources from where India imports. India mainly imports from China but imports from other Southeast Asian countries such as Vietnam and Thailand have increased over the years. India had imposed increased tariffs on imports of solar cells and modules from China and Malaysia in 2018, which helped control imports (See Table 2 and Figure 4.)<24> However, the tariffs did not apply to other countries. India is a growing market, and the domestic industry faces competition not just from China but many other countries that view India as a key market destination.

Table 2. India’s Top Import Sources of Solar Cells (in US$ Million)

Data source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry<25>

Data source: Ministry of Commerce and Industry<25>

Figure 4. India’s Imports of Solar Cells/Modules (by Country; Other than China)

Data from Ministry of Commerce and Industry<26>

Data from Ministry of Commerce and Industry<26>

In 2018, the government increased import tariffs on renewable products to help domestic manufacturers and extended the validity of the rates till July 2021.<27> This is a necessary step given the competition facing the sector. However, an imposition for only a year would not provide sufficient protection to expand manufacturing to the level that is required. For investment decisions to be made, a longer time period would ensure certainty and protection. Further, this order included China, Thailand and Vietnam, but excluded Malaysia — this means the imports from the country will likely increase. The government, in its 2021 Budget, has announced higher tariffs on solar lanterns and inverters. However, given that domestic manufacturing is inadequate, this measure may not serve the intended purpose of providing protection to the industry at this stage. Tariffs may become useful in a few years, when manufacturing picks up.

Indeed, in the past, uneven protection has hurt the solar industry. In the domestic content requirement (DCR) scheme, the exclusion of thin films led to a contraction of the domestic supply of crystalline silicon production in India. It led to a situation where India is dominated by thin film in PV installations, as compared to the global market where crystalline silicon holds the majority share. There is a need to bring thin films under DCR.

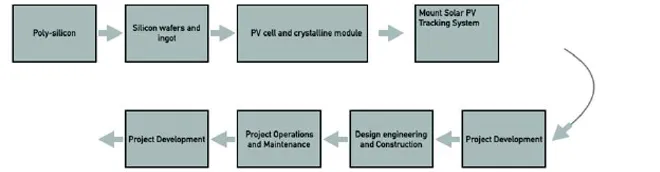

Figure 5 shows the various components of the supply chain, from manufacturing to operation and maintenance. At present, the majority of manufacturing in India is centred around cell and module assembly, which is mainly downstream manufacturing.

Upstream manufacturing of polysilicon, wafer and ingots is technology — and capital-intensive, and globally, only a few companies constitute a majority of the manufacturing. Module and PV cell manufacturing is almost completely dependent on imports for raw materials.

Figure 5. Supply Chain of the Solar Energy Industry

Source: Author’s own, using various sources

Source: Author’s own, using various sources

The industry needs financial support to scale up production. India would need to provide low-cost financing to manufacturers to be able to compete with Chinese goods. India’s PV production has shifted from mainly public production in the 1970s to private production by the late 1980s. Access to finance at competitive costs is one of the most difficult challenges to investment in the solar energy sector. Further, the industry is highly capital-intensive, and developers require capital throughout the life of the technology. Indian companies in Rajasthan and Gujarat have financed their projects under the first phase of the National Solar Mission (NSM) through loans from the US Exim Bank. But this has also meant sourcing components from the US’ manufacturing base.<28>,<29> Thus, these loans cannot be the main source of funding for domestic manufacturing, as they carry a foreign currency risk.

India has taken various measures to support manufacturing in the renewable sector through the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission (JNNSM), Modified Special Incentive Package Scheme (MSIPS),<30> and ‘Make in India’ which provides incentives and subsidies. However, as imports remain more cost-effective, higher-capacity domestic production remains difficult. Many companies have also filed for debt restructuring on account of lack of demand.

In November 2020, the Cabinet approved a scheme to introduce production-linked incentive (PLI) to the solar industry for an amount of INR 45 billion.<31> The policy aims to incentivise domestic production. The incentive should be linked to output as well as standard quality specifications. The second phase of JNNSM introduced viability gap funding (VGF) and Generation Based Incentive (GBI) as funding mechanisms. The VGF does not incentivise production but compels suppliers to go for low-quality components to keep prices low. This has led to low power tariffs, which in turn have put into question the viability of projects. For example, banks such as SBI are no longer lending to projects that sell below a certain tariff level due to questions on their viability.<32> The lower participation by scheduled banks is worrisome, as countries like Brazil and China have shown that public banks play an important role in supplying credit to the renewable sector. Therefore, more innovative financing methods to increase long-term low-cost funding from banks need to be explored. Credit enhancements for developers can be explored, which will enable them to attain higher credit rating and raise funds from the bond market.<33>

India has high cost of capital. It can learn from Brazil which has similar cost of debt and has done well in adding capacity in renewable energy in recent years. Brazil has been successful in providing low-cost long-term finance through the National Social Economic Development Bank (BNDES) that provides majority of the financing for renewable infrastructure.<34> It has partnered with development banks in other countries to set up credit lines to support projects in Brazil, and has mandated local content as a prerequisite for access to credit. This model may be studied by Indian policymakers to enable a similar financing pattern in the country.

Moreover, technological advancements are taking place at a rapid pace in this sector. R&D is essential to keep in touch with the fast-changing market and produce at more competitive prices. The solar sector has seen disruptive innovations in the past few decades. The sizes of solar cells and modules are also continuously increasing. This means there is a need for additional capital investments by cell and module manufacturers to adapt to the larger sizes and install new production systems. For example, there is an emerging technology called the Cells of Passivated Emitter Real Cell (PERC), which requires the current cell and module production processes to be retrofitted. Thus, in addition to high upfront cost of capital equipment, there is a need for continuous capital expenditure to keep up with the changing technology. To be sure, India is conducting R&D at the national level.<35> This has to be strengthened by exploring relevant opportunities for international collaborations. A clear road map to develop the next generation of technology is required, outlining specific targets and timelines.

The industry needs long-term strategic planning to nurture domestic manufacturers that can effectively take on the imports from abroad. In the long run, it will be feasible to indigenise the entire supply chain. At present, a more focused approach to indigenise certain segments of the supply chain, coupled with lower import duties or import tax exemptions for those components that need to be imported, can help the government arrive at an optimal combination of policy options. There is a need to provide an entire ecosystem to give a boost to manufacturing: land, cheap credit, funds for research, cash incentives, and tax rebates. The concept note on manufacturing solar PV scheme was shared with stakeholders in 2017.<36> India should create a road map and vision on how to localise the manufacturing for the entire country with coordinated efforts with state governments.

Renewable purchase obligation (RPO) is also an important component for the development of manufacturing in renewable energy. It provides the necessary demand pull. It requires distribution companies (discoms) to mandatorily purchase a certain percentage of their total power from renewable sources. But it is often not implemented as expected and there are delays in imposing penalty for noncompliance. This issue is even more acute for the solar industry due to falling solar tariffs and lower average power procurement<37> by discoms that has led to uncertainly about the revenues for solar power projects. These issues are recognised and steps are being taken to address them.<38>

1. Protection and support to domestic industry — While protection may be needed to help the industry face competition from cheaper imports, they should be with the aim of helping the industry grow more competitive. These should come with a specific timeline so as not to make the industry dependent on them and make them inefficient in the long run. The government’s decision to stop the system of feed-in tariffs in 2017 for the wind industry led to losses for the wind turbine industry. Suzlon, for example, has incurred huge losses as a result of the shift to auction-based system.<39> Thus, it is important to implement protection with properly defined sunset clause.

a. < style="text-decoration: underline">Import duties on solar cells and modules — The time period for this should be announced beforehand with a minimum of 5 years so as to allow manufacturing to respond. However, given the dependence on imports, this could increase the cost of production for the sector as well. In 2013, the Finance Ministry decided to not implement the anti-dumping duties recommendation submitted by the Directorate General of Anti-Dumping and Allied Duties (DGAD) following lobbying efforts by the power ministry. Thus, other measures to provide subsidy on production will have to balance the initial increase in cost on inputs for domestic producers.

b. < style="text-decoration: underline">Production subsidy can be provided for small manufacturers or larger firms up till a certain production limit. It should be introduced with a clear timeline and a sunset clause. The government has recently announced a PLI scheme in the budget.

c. < style="text-decoration: underline">Domestic Content Requirement (DCR) for solar energy procurement — This will help increase the capacity utilisation to 100 percent and bring down the cost of BOMs as compared to China. This works if there is some level of sunset clause. It should not become a clutch.

2. Manufacturing parks for both wind and solar companies. This could be based on the Gujarat solar manufacturing that has been set up. It should be with plug and play model with land availability, low-cost power and other incentives.

3. R&D — The example of how the wind industry (as explained in the case of Suzlon) developed in terms of technological progress should be used to aid the solar industry. Technological progress with foreign collaborations and joint ventures should be encouraged. The government should also initiate programs with counterparts in the US and Europe to learn from experience and expertise. It should be a central focus area when negotiating India’s trade deals.

4. Standardised quality criteria at various stage of the supply chain — As different segments of the supply chain develop, there is a need for harmonising the market by setting standards for quality at the various stages and to create a system of auditors who can regularly evaluate and certify. The standards need to be aligned with international ones.

Hydrogen energy is becoming an important new low-carbon technology. Its adoption in transportation, production and storage for renewable power energy can help make significant contributions to the future of cleaner energy. To balance the variable renewable sector, hydrogen can provide cost-effective storage option, as compared to batteries, that can store energy for several day or weeks. The current global demand is at 70 Mt but is expected to multiply many times by 2050.

Almost all of the hydrogen produced today is from fossil fuels. The cost of producing it from renewable source remains higher than from other sources. India would require coordinated policy initiatives to identify potential demand sites so as to scale up production, carry out research nationally as well as through international cooperation, and identify low-cost storage options for hydrogen. As per a study by CEEW, only aggressive price reduction in the cost of electrolyser and storage technologies would make the price of hydrogen competitive by the next decade.<40> Hydrogen produced from green sources will help curb carbon emissions. R&D to help reduce cost will be critical. Currently, hydrogen is used in refinery to remove sulphur from fuels. Countries such as Japan have been at the forefront but other countries such as the US and China are also outlining ambitious plans to scale up hydrogen production in the coming years.

This is an opportunity for India to be a maker of technology and lead in this sector rather than perpetually playing catch-up. The government has decided to launch a plan to build hydrogen plants that will be produced from renewable power sources.<41> The budget presented recently also announced a National Hydrogen Mission as well as the setting up of a National Research Foundation with an outlay of INR 50,000 crores to strengthen research in new technology. Long-term vision for the development of future technologies will be essential.

Access to new technology is crucial to the ability of developing countries to transition to cleaner energy. It is also key to mitigating the adverse effects of climate change. In turn, technology transfer — and consequently, bridging the technological gap between developed and developing countries — is dependent on trade. This takes place through different channels — international trade in goods and services, FDI, licensing, joint ventures, agreements between governments, and non-market channels such as imitation.

The need is for transfer of technology at a reasonable cost to developing countries. Despite the importance of transfer of technology, it remains a contentious issue, and developed and developing countries have yet to find common ground. Indeed, transfer of technology is costly. Over the years, however, technological and finance advancements have led to falling costs in energy transition, especially owing to the technology changes that have led to improved efficiency.

India recognises the need for technology transfer, and over the years has liberalised foreign direct investment (FDI) rules in almost all sectors. In the renewable energy sector, FDI is permitted up to 100 percent under the automatic route. The investment in the sector surpassed US$ 1 billion for the first time in 2017-18.<42> The government has undertaken measures to attract investments for manufacturing solar cell, electric vehicles, and battery storage systems. Globally, India is the biggest market: in 2019, it attracted venture capital or private equity investments in renewables worth US$ 1.4 billion.<43>

Technology transfer through FDI can happen through reverse engineering, movement of labour, and integration into the global supply chain. Another form of technology transfer is internalisation of R&D by large firms such as multinational companies (MNCs). Larger Indian firms have also been able to tap into the global R&D systems. For example, Suzlon has set up R&D centres in Germany, Netherlands and Denmark, apart from the one in India. Companies in India and China have also facilitated transfer of technology through acquisition of firms abroad, as well as cooperation with research institutions in developed countries and local R&D centres. A combination of different channels and interactions for transfer of technology has been undertaken. However, with India becoming a primary market, foreign companies see domestic manufacturers as competitors, leading to a disincentive to transfer technology. Companies such as Suzlon have acquired technology from smaller companies in the developed countries that had little to lose from international competition.

Leading companies have the resources to pool together local and international knowledge flows to acquire technology, but small and medium enterprises do not enjoy the same leverage. After all, transfer of technology involves significant investments in experimentations and organisational structures. Further, much of current innovation still happens in the US and Europe and there is a need to facilitate their transfer. Therefore, there is possibility of active policy interventions. What is needed is international collaboration with an aim to achieve development goals. Government can help establish links between local and international firms to facilitate such transfers with an emphasis on green technology. The next steps would be to attract FDI that will help deliver long-term benefits through indigenisation of technology, which in turn can lead to further innovations. India is already preparing to study FDI trends to analyse how policy can be effectively reviewed to ensure greater transfer of technology.<44>

India, through the International Solar Alliance (ISA), can help foster greater collaborations. There is a gap at the international level for collaboration that is purely for meeting development or poverty alleviation issues. Through ISA, countries can help identify specific needs and pool resources – both financial and human– to achieve specific targets. Network of collaborations between scientists and researchers from top universities across nations needs to be strengthened. A fund dedicated to advancements in specific renewable technologies should be set up. There is a need to set specific targets and deliverables to be achieved in a given period with industryuniversity research cooperation.

The innovations thus achieved can be given the status of public goods. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the development of vaccines. There is international cooperation in transferring technology so as to allow medicines to be produced at affordable prices. There is a need to build a similar narrative for green technologies and build mechanisms that would facilitate technology transfer and cooperation.

Demand for renewable sources of energy will only grow manyfold in the future as more countries transition to cleaner sources of energy and cost of renewable energy continues to fall. India would need to implement policies that will push the renewable sector to grow and meet this demand. The demand for renewable sources such as wind and energy, for instance, is subject to fluctuations and therefore the prerequisite is technological progress that can provide a steady source of energy.

India will have to formulate policies to stay ahead in terms of technology upgrades in the solar and wind sector, as well as newer sources of energy such as green hydrogen. India can also play an important global role by forging partnerships with both developing and developed countries to enable further research in newer technologies and facilitate technology transfer.

<2> “Corporate Clean Energy Buying Leapt 44% in 2019, Sets New Record” 28 January 2020, BloombergNEF.

<3> Global Trends in Renewable energy investment 2020, United Nations Environment Program and Bloomberg New Energy Finance (2020) Report 2020

<4> Same as 2

<5> Annual Report 2019-20, Ministry of New and Renewable energy.

<6> “An Overview of All the Wind Based Energy Companies in India”, 07 September 2016, Economic Times.

<7> David Rasquinha, “Winds of Change”, Exim Bank India blog.

<8> David Nurse, “2019 Top 10 Wind Turbine Manufacturers — Wind Supplier Analysis”, 31 July 2019.

<9> Generation Based Incentive Scheme, 16 December 2011, Press Information Bureau.

<10> M Ramesh Chennai, “Renewable energy ministry rules out removal of tariff caps”, 13 November 2019.

<11> R. Sree Ram, “Wind power auction success is bittersweet news for Suzlon” 03 March 2017, Livemint.

<12> Export Import data, Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

<13> Export Import data, Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

<14> “A High Level Delegation from Uruguay Visits the Manufacturing Facility of RRB Energy Limited at Poonamallee,” 07 March 2011, BusinessWire.

<15> Sufang Zhang et al. “Interactions between renewable energy policy and renewable energy industrial policy: A critical analysis of China’s policy approach to renewable energies”.

<16> Marc Prosser, “China Is Taking the Worldwide Lead in Wind Power,” 04 April 2019, Singularity Hub.

<17> John Parnell, “Siemens Gamesa Launches 14MW Offshore Wind Turbine, World’s Largest,” 19 May 2020, Green Tech Media.

<18> “India needs to lower its logistics cost to 7-8% of GDP: Report,” 23 December 2020, The Statesman.

<19> Sutanuka Ghosal, “RBI must ensure rupee export credit at repo rate: EEPC India,” 07 June 2019, Economic Times.

<20> “Top 10 players consolidating solar market in India: Report,” 29 April 2020, Economic Times.

<21> Rishabh Jain et al. “Scaling up Solar Manufacturing in India to Enhance India’s Energy Security,” Aug 2020, Centre for Energy Finance.

<22> “Surya to Boost Solar Manufacturing in India,” August 2018, Shakti Foundation.

<23> Utpal Bhaskar, “New tariffs on import of solar cells and modules on the cards,” 14 December 2020, Hindustan Times.

<24> Ministry of Finance, Notification No. 01/2018-Customs (SG), 30 July 2018.

<25> Export Import data, Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

<26> Export Import data, Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

<27> Utpal Bhaskar, “New tariffs on import of solar cells and modules on the cards,” 14 December 2020, Hindustan Times.

<28> Craig O’Connor, “Financing Renewable Energy: The Role of Ex-Im Bank,” EXIM Bank USA.

<29> “U.S. Export-Import Bank Signs $5 Billion Memorandum of Understanding with Reliance Power to Support American Exports to India’s Energy Sector,” 07 November 2010, EXIM USA.

<30> Guidelines for revised M-SIPS, 24 February 2016, DeitY.

<31> “Cabinet approves PLI Scheme to 10 key Sectors for Enhancing,” 11 November 2020, PIB.

<32> Utpal Bhaskar, “PMO steps in to ease supply of credit to green energy firms,” 30 September 2019, Livemint.

<33> Vaibhav Pratap Singh et al. “RE-Financing India’s Energy Transition,” July 2020, CEEW.

<34> Lucas Morais and Mariana Yaneva, “Financing Renewable energy in Brazil,” November 2018, BIREC.

<35> Annual report 2018-19, MNRE.

<36> Indian Solar Manufacturing Concept Note, MNRE.

<37> Twesh Mishra, “Renewable purchase obligation compliance remains low in most States,” 07 July 2020, The Business Line.

<38> Rakesh Ranjan, “Rajasthan Regulator Says DISCOMs Not to be Blamed for Failure to Meet RPO Targets,” 15 October 2020, MercomIndia.

<39> “How wind market disruption drove Suzlon to financial ruin,” 19 July 2019, Livemint.

<40> Tirtha Biswas, “A Green Hydrogen Economy for India,” December 2020, CEEW.

<41> Utpal Bhaskar, “India to launch National Hydrogen Energy Mission,” 26 November 2020, Livemint.

<42> “3,217 Million US$ received as FDI in Renewable Energy Sector", 27 December 2018, PIB.

<43> Same as 1

<44> Arun S, “Centre analyses FDI data to boost tech transfer,” 14 January 2018, The Hindu.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

Nandini Sarma was a Junior Fellow with the Green Transitions Initiative at ORF. Her research focuses on growth trade and climate.

Read More +