The energy problem in India is often framed as one of supply scarcity: India does not have adequate primary energy resources and insufficient energy production capacity which results in supply shortages; this in turn limits energy consumption. In reality, India’s key energy problem is one of inadequate effective demand for energy, especially from poor rural households in India and an underdeveloped market for energy. Globally, India is the third largest market for energy but the “largeness” is derived from quantity and not quality. Millions of households consume small quantities of energy mostly for cooking and lighting that adds up to a large sum. India’s per person commercial energy consumption (not including unprocessed biomass consumption) estimated at 25.7 gigajoules (GJ) per year in 2022 is only about a third of the world average; it is the lowest among G20 countries and lower than the minimum required for decent living in tropical countries. India has the largest share of the population with an energy access deficit estimated at over 505 million. It is not difficult to see why.

Millions of households consume small quantities of energy mostly for cooking and lighting that adds up to a large sum.

Disposable incomes are low in rural households which means there is not enough money to spend on energy for cooking, lighting, heating, transport or communication. Poor family wage earners are paid weekly which limits energy and other essential purchases to small quantities. A South Indian entrepreneur took note of this trend and started marketing grooming products like soap and shampoo in small sachets in rural India in the 1980s. The availability of these products in tiny (3-4 grams) convenient packets opened a new market for hygiene and grooming products in rural areas. The small quantity purchased many times over meant that the poor paid more per unit of a given product than the rich who bought these products in larger volumes. Large multinational consumer goods companies were forced to adopt the sachet model as the sale of small shampoo sachets boomed in India. Labelled the Indian “sachet revolution”, this development is widely studied in business circles. Estimates of the share of shampoo sachets (single use) in total shampoo sales vary, but by most accounts, it is far more than 50 percent. The “sachet revolution” can be replicated in the context of energy with modular energy forms such as LPG (liquid petroleum gas canisters) that can be packed and sold in canisters of many sizes and transported by road, sea or rail.

Energy in Sachets

The UN (United Nations) General Assembly has placed energy decentralisation central to the pursuit of SDG7. The role of decentralised energy solutions that were once considered the most suitable for rural India is now overlooked in the context of policy priorities to increase centralised energy solutions, especially for the supply of grid-based electricity. The infrastructure for countrywide electricity supply is already in place but the economics of electricity supply to the rural poor remains a challenge. The effective demand for electricity from rural households remains small as in the case of soaps and shampoos. This means that electricity distribution companies often lose money on every unit of energy supplied to rural households. Long distances increase technical losses that add to financial losses.

The infrastructure for countrywide electricity supply is already in place but the economics of electricity supply to the rural poor remains a challenge.

LPG, a modular energy form whose distribution is independent of the transmission grid and gas pipelines needs to be considered as a decentralised bridge fuel until RE with storage options becomes dependable and affordable. Small canisters of LPG (propane and butane) can provide decentralised fuel for cooking, lighting and small-scale industrialisation and also facilitate a gradual move away from subsidised LPG among the rural poor. LPG is not a greenhouse gas (GHG) as per the classification of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on climate change) and it is among the clean cooking fuels listed by the WHO (World Health Organisation). LPG can go in where natural gas and electricity cannot: small canisters of LPG can be safely carried by men and women, and larger canisters can be transported by trucks, trains and boats. When LPG replaces other fuel technologies such as heating oil, solid fuel and even grid-based electricity in India, there are significant carbon savings.

In terms of security of supply, LPG is among the most secure among conventional forms of energy. LPG is an inevitable byproduct of the oil refining and natural gas extraction processes. It will exist as long as society demands that these two processes happen. LPG is freely traded around the world and scores twice as highly as both petrol and diesel on the OECD’s (Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development) trade openness index. It is also a fuel that is less susceptible to political instability due to its dual-source origins and variety of transportation options—ships, trains, boats, and trucks. Unlike natural gas and crude oil which are exposed to high price volatility, the price of LPG is relatively stable and predictable.

LPG is freely traded around the world and scores twice as highly as both petrol and diesel on the OECD’s (Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development) trade openness index.

The argument that rural India should leapfrog into RE (renewable energy) solutions rather than use fossil fuels like LPG is premature from an economic perspective and inequitable from a social justice perspective. Decentralised (off-grid) RE solutions with storage are unaffordable even for affluent urban households. Most urban households use LPG or PNG (piped natural gas), petrol & diesel and grid-based electricity as key sources of household energy which together carry a large carbon footprint. Mandating that the rural poor should use RE-based solutions will not only take away their right to choose but also impose undue costs on them. Effectively RE solutions imposed on the rural poor would be a climate subsidy extracted from the poor by the rich.

Challenges

Even at a subsidised price of INR 603 for a 14.2 kg canister in 2023, LPG remains unaffordable for many poor households in India. As per information conveyed in the upper house of the Indian Parliament in December 2023, the consumption of subsidised LPG cylinders is on average just 2.8 cylinders per household per year. The method used to arrive at this figure is not clear but in general procurement of a tradable subsidised good (such as LPG) does not necessarily confirm use and the actual consumption of LPG by poor households may be lower. In urban households, the average number of 14.2 kg LPG canisters used is over 9 per year. Among the reasons for the low consumption of subsidised LPG by the poor are low incomes that make even subsidised LPG unaffordable, cooking limited to one or two times a day and the availability of biomass-based fuels at low or no cost (except of course the opportunity cost of female labour). Smaller canisters may improve adoption and use of LPG in rural areas but the experience of 5 kg LPG canisters introduced by public sector oil marketing companies in the early 2010s is not very encouraging. Among the reasons are the fact that the number of dealers and retail outlets for 5 kg “free trade” LPG canisters is limited and the price of the 5 kg LPG canister is too high for a typical single-income poor household. The small LPG canisters target populations with no proof of address in urban areas and not the poor in rural areas. If the 5 kg LPG canisters are sold primarily in rural markets at reasonable (not subsidised) prices, it is likely to be adopted in rural kitchens. Applications of LPG in lighting and power generation can also be introduced in rural areas which may initiate investment in small-scale industries and create demand for LPG. LPG can also serve as a robust and affordable backup source for off-grid RE solutions. As LPG supply does not require specialised infrastructure, LPG can be replaced with renewable LPG (rLPG) when it becomes affordable and available. This will necessarily mean a focused policy for the promotion of small LPG canisters to improve access to cooking fuels, reduce carbon emissions and prepare for the energy transition.

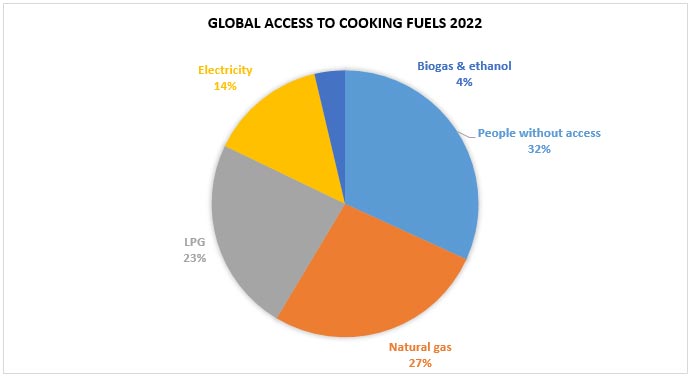

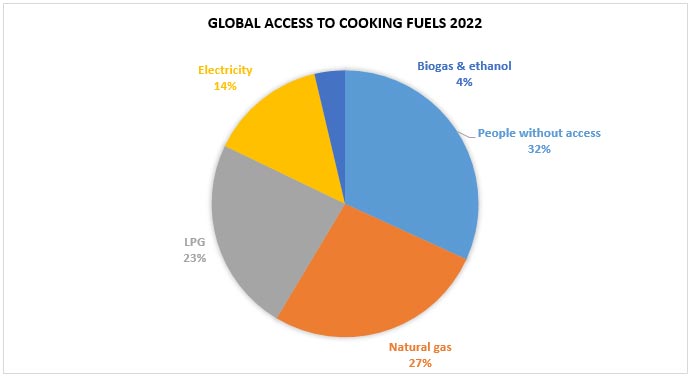

Source: International Energy Agency

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation.

Akhilesh Sati is a Program Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

Vinod Kumar Tomar is a Assistant Manager at the Observer Research Foundation.

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.

PREV

PREV